Imagine strolling through New Jersey’s lush parks only to find alien invaders lurking in the shadows… fish that walk on land, bugs that rain sticky goo, and vines that strangle trees like sci-fi villains.

These invasive species aren’t just quirky; they’re disrupting ecosystems, costing millions in damage, and threatening native wildlife.

We’ll unmask the top 25 culprits, complete with reasons they’re a problem and tips to keep the Garden State green.

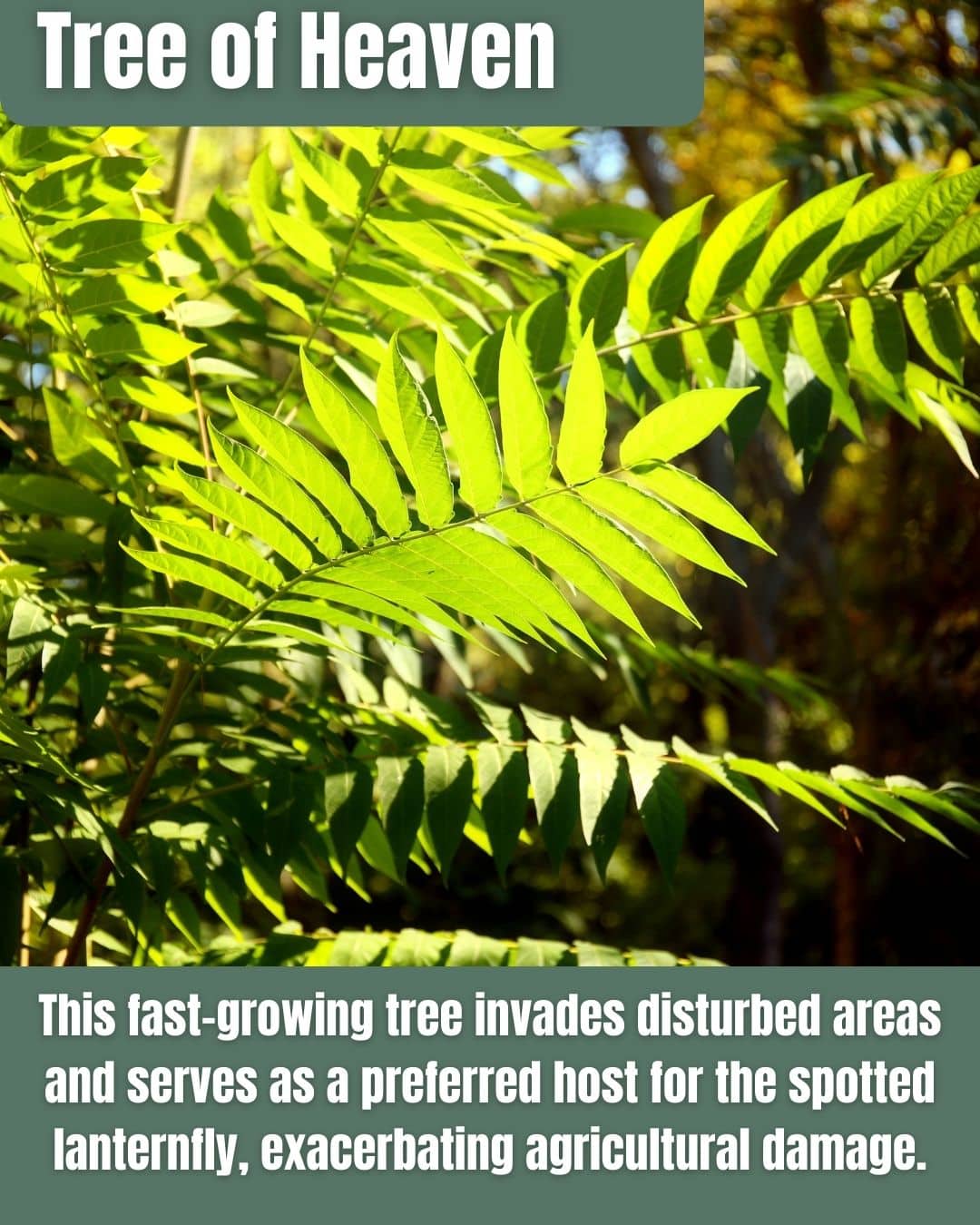

1. Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

- Thrives in New Jersey’s polluted urban lots and disturbed soils, tolerating drought and poor conditions where natives struggle.

- Interesting fact: Serves as the preferred host for the spotted lanternfly, amplifying agricultural damage in NJ since 2018.

- Grows up to 80 feet tall, producing over 300,000 seeds per tree annually for aggressive spread.

The Tree of Heaven, introduced to the US in 1784 as an ornamental, has become a notorious invader in New Jersey, colonizing roadsides, abandoned lots, and forests.

Its rapid growth (up to 6 feet per year) and allelopathic chemicals inhibit nearby plants, reducing biodiversity.

In NJ, it’s a key host for the destructive spotted lanternfly, costing millions in crop losses.

Control involves cutting and herbicides, but its root suckers make eradication tough. Public reporting via apps aids early detection in urban areas like Newark and Camden.

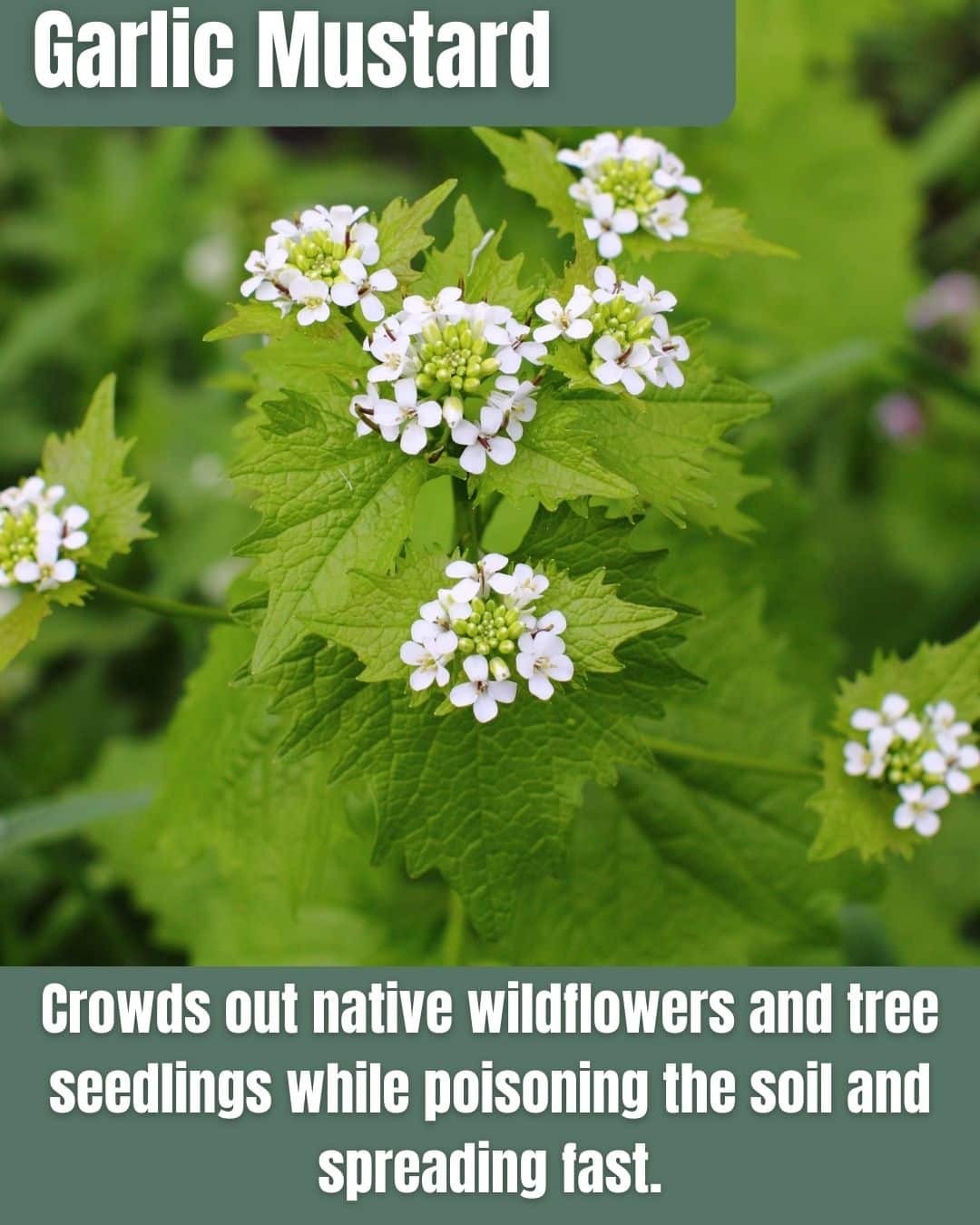

2. Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

- Flourishes in New Jersey’s moist, shaded woodlands, outpacing natives with a biennial life cycle and prolific seed production.

- Did you know? Releases allelochemicals that disrupt beneficial soil fungi, harming tree regeneration in NJ forests.

- Avoided by deer, allowing unchecked spread while natives are browsed, leading to dense patches.

Garlic Mustard, a European biennial herb, invades New Jersey’s wooded areas, forming dense stands that displace spring wildflowers like trillium.

First-year rosettes overwinter, bolting to flower in year two and producing up to 8,000 seeds per plant, viable for five years.

Its allelopathy alters soil, reducing mycorrhizal associations essential for natives. In NJ, it’s widespread in parks like the Pinelands, threatening biodiversity.

Edible to humans, but pulling before seeding is key. Community “pulls” in spring help control, though roots must be fully removed to prevent regrowth.

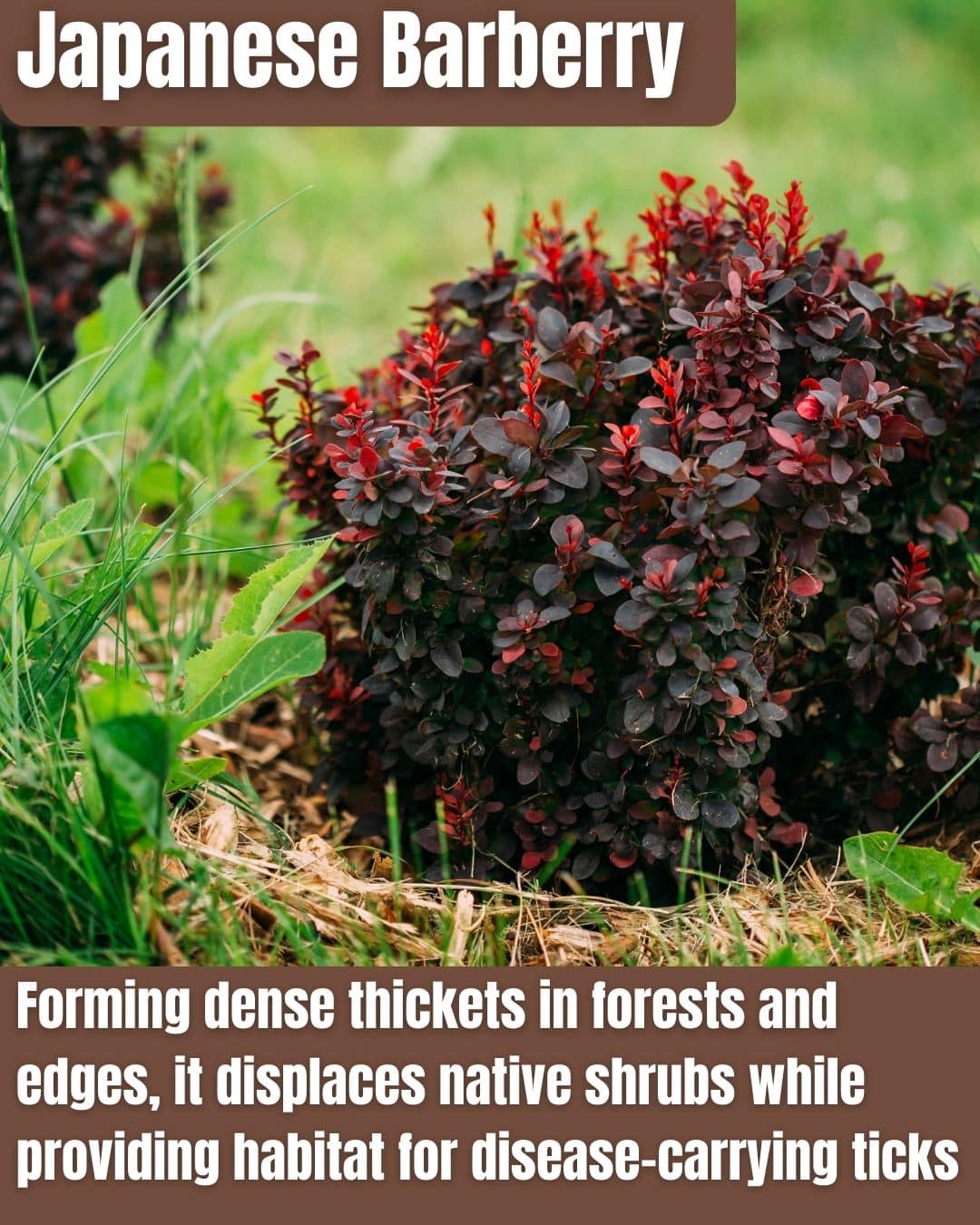

3. Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

- Succeeds in New Jersey’s varied soils and partial shade, with deer resistance enabling survival where natives are eaten.

- Interesting fact: Dense thickets raise soil pH and create microhabitats boosting tick populations, increasing Lyme disease risk in NJ.

- Prevalent in 29% of northern NJ forest plots, escaping landscaping to invade open fields and edges.

Japanese Barberry, introduced from Asia in 1875 for hedges, has overrun New Jersey forests, forming spiny thickets that exclude native shrubs like blueberry.

Its bright red berries, dispersed by birds, aid spread, while roots alter soil chemistry. In NJ, studies link it to higher tick densities, exacerbating Lyme cases in areas like the Highlands.

Tolerant of poor soils and drought, it thrives post-disturbance.

Removal involves digging or herbicides; replacing with natives like inkberry reduces risks.

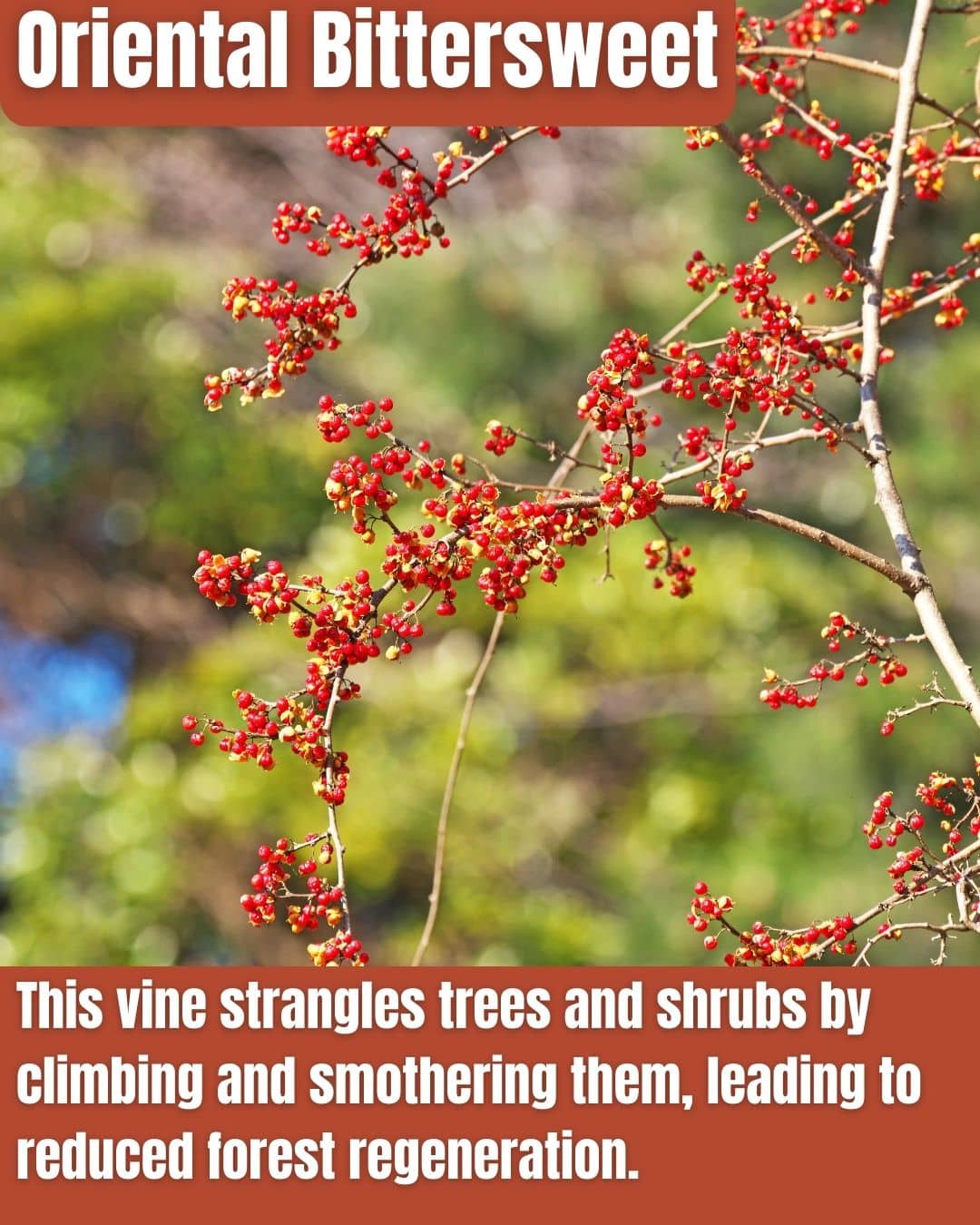

4. Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus)

- Prospers in New Jersey’s sunny edges and disturbed sites, with shade tolerance allowing forest infiltration.

- Overproducer: Produces 200 times more pollen than native bittersweet, hybridizing and outcompeting it in NJ.

- Vines grow up to 60 feet, dispersed by birds eating colorful fruits, leading to rapid colonization.

Oriental Bittersweet, brought from Asia in the 1860s as an ornamental, aggressively invades New Jersey fields, forests, and roadsides, girdling trees with heavy vines that cause breakage during storms.

Its rapid growth (up to 12 feet yearly) and prolific seeds (up to 370 per vine) enable dominance.

In NJ, it alters habitats in places like the Delaware Water Gap, reducing wildlife value.

Tolerant of varied soils, it spreads via birds and humans. Control requires cutting vines and treating stumps; prevention includes avoiding the decorative use of these plants in wreaths.

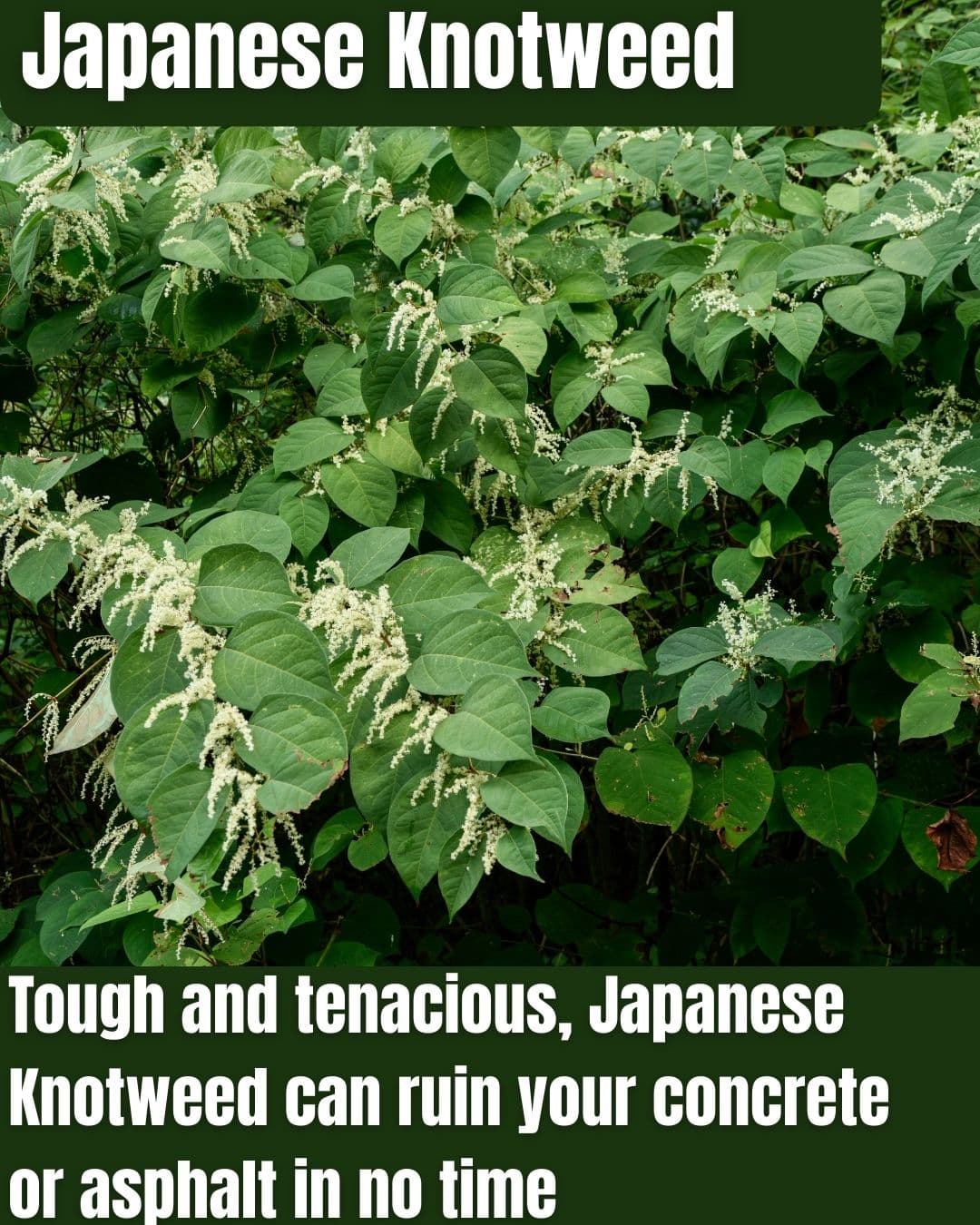

5. Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

- Excels in New Jersey’s moist, disturbed riparian zones, regenerating from tiny root fragments.

- Interesting fact: Roots extend 20 feet, damaging infrastructure like pipes and foundations in urban NJ areas.

- Grows up to 10 feet tall in weeks, forming dense stands that erode soils and block waterways.

Japanese Knotweed, introduced from Asia in the 1800s for erosion control, dominates New Jersey streambanks and roadsides, creating monocultures that displace natives and increase flood risks.

Its bamboo-like stems die back in winter, but extensive rhizomes (up to 65 feet) allow resurgence.

In NJ, it’s rampant in the Meadowlands, costing thousands in removal. Tolerant of poor soils and pollution, it spreads via fragments in soil or water.

Effective control uses herbicides like glyphosate; biological agents like psyllids are under trial. Young shoots are edible, akin to rhubarb.

6. Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora)

- Thrives in New Jersey’s full to partial sun with well-drained soils, avoiding extreme cold below -28°F.

- One plant can produce up to 500,000 seeds yearly, remaining viable in soil for 20 years.

- Designated noxious in NJ, it forms dense thickets post-disturbance, outcompeting natives in pastures and edges.

Multiflora Rose, an Asian shrub introduced in the 1800s for erosion control and wildlife habitat, has become a pervasive invader in New Jersey, dominating fields, forests, and roadsides with arching canes up to 15 feet.

Its white-to-pink flowers yield red hips dispersed by birds, enabling rapid spread. In NJ, it reduces biodiversity in areas like the Pinelands, creating barriers that limit recreation.

Tolerant of varied soils but prefers infertile ones, control involves mowing or herbicides; goats offer eco-friendly grazing. Still sold in some nurseries despite bans elsewhere.

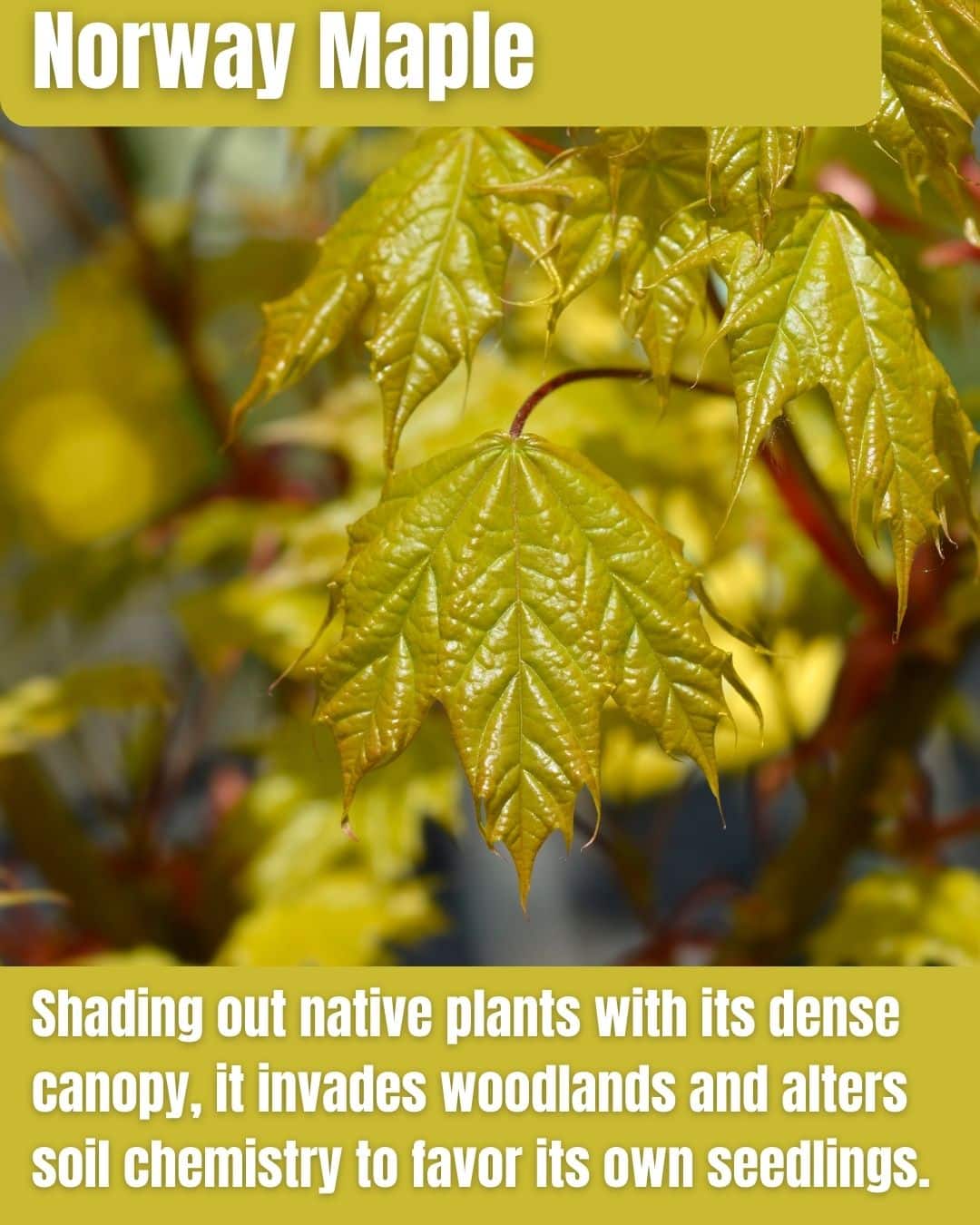

7. Norway Maple (Acer platanoides)

- Succeeds in NJ’s urban environments due to drought, pollution, and poor soil tolerance, plus rapid growth.

- Interesting fact: Wind-dispersed seeds invade woodlands, shading out natives like sugar maples.

- Branches prone to storm breakage, causing cleanup costs in NJ municipalities.

Norway Maple, imported from Europe in the 1700s as a street tree, now invades New Jersey forests and suburbs, outcompeting natives with allelopathic chemicals and heavy shade.

Growing up to 50 feet, its samaras spread widely, altering soil pH. In NJ, it’s common in the Highlands, reducing diversity and impacting pollinators.

Tolerant of compaction and salt, it thrives post-disturbance but weakens in storms.

Removal favors natives like red maple; some debate its urban utility, but invasiveness prompts bans in areas.

8. Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

- Flourishes in NJ’s wet soils and full sun, with partial shade tolerance via air-spaced stems.

- A single plant produces 2.7 million seeds, disrupting water flow and native foods.

- Invades riparian areas, outcompeting grasses and sedges in NJ wetlands.

Purple Loosestrife, a European perennial introduced in the 1800s via ballast, dominates New Jersey wetlands, forming monocultures that diminish habitat for fish and birds.

Tall spikes of purple flowers attract pollinators but offer poor nutrition. In NJ, it’s widespread in the Meadowlands, reducing plant diversity and increasing flood risks.

Tolerant of flooding, it spreads via seeds in water. Biocontrol beetles have reduced populations since the 1990s; manual pulling works for small infestations, though roots regenerate if not fully removed.

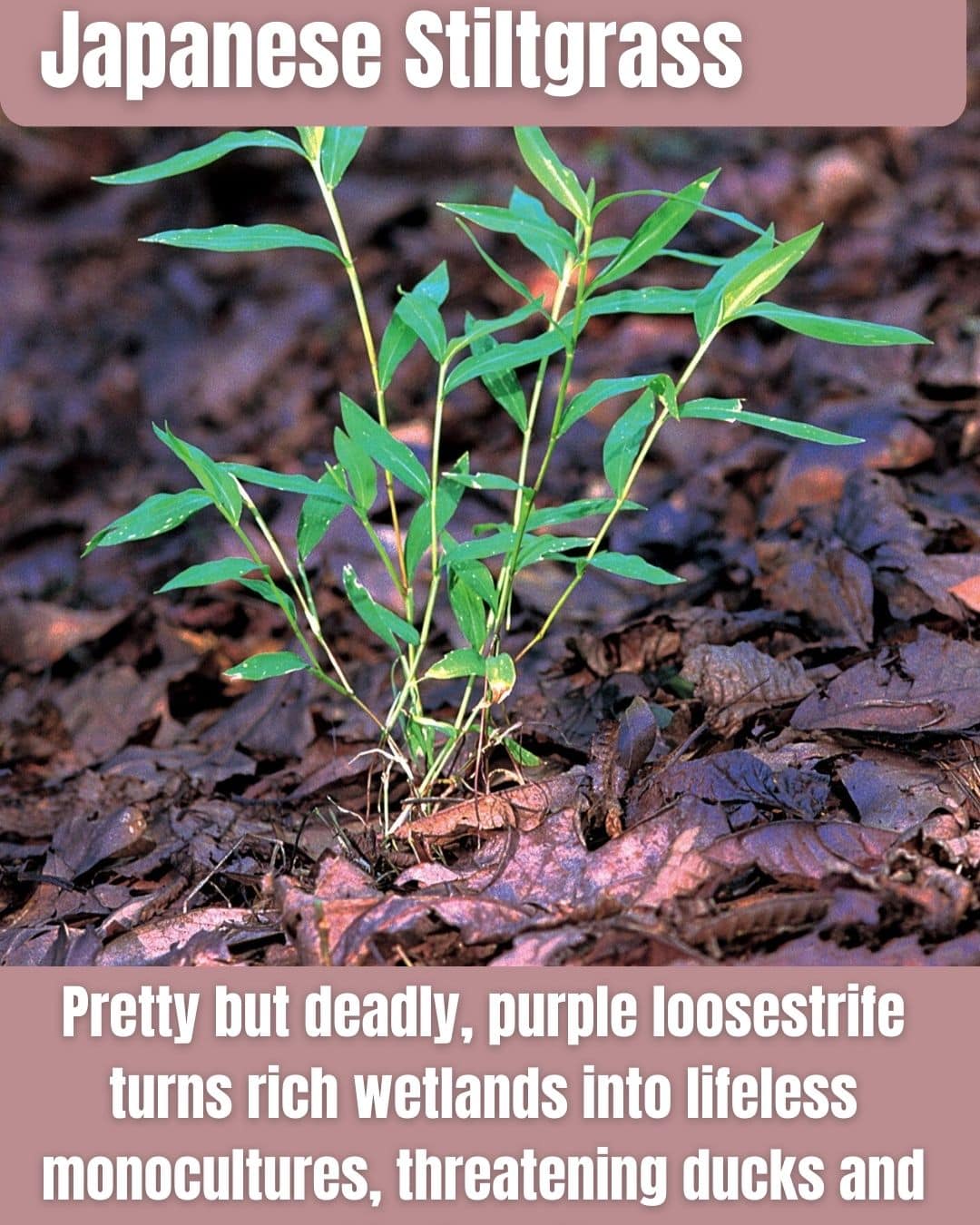

9. Japanese Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum)

- Adapts to NJ’s shaded forests and sunny moist areas, thriving with adequate moisture.

- Covers 5-10% of NJ forests, altering soil layers and increasing fire risk.

- Annual seeds spread via hikers and animals, outcompeting natives in disturbed sites.

Japanese Stiltgrass, an Asian annual introduced in the 1910s as packing material, invades New Jersey woodlands and roadsides, forming dense mats that prevent tree regeneration.

Growing 1-3 feet with bamboo-like leaves, it alters nitrogen cycling. In NJ, it’s emerging in the Watchung Mountains, exacerbating erosion.

Tolerant of low light and nutrients, it spreads rapidly post-logging. Control via timed mowing before seeding or herbicides; prevention includes boot cleaning.

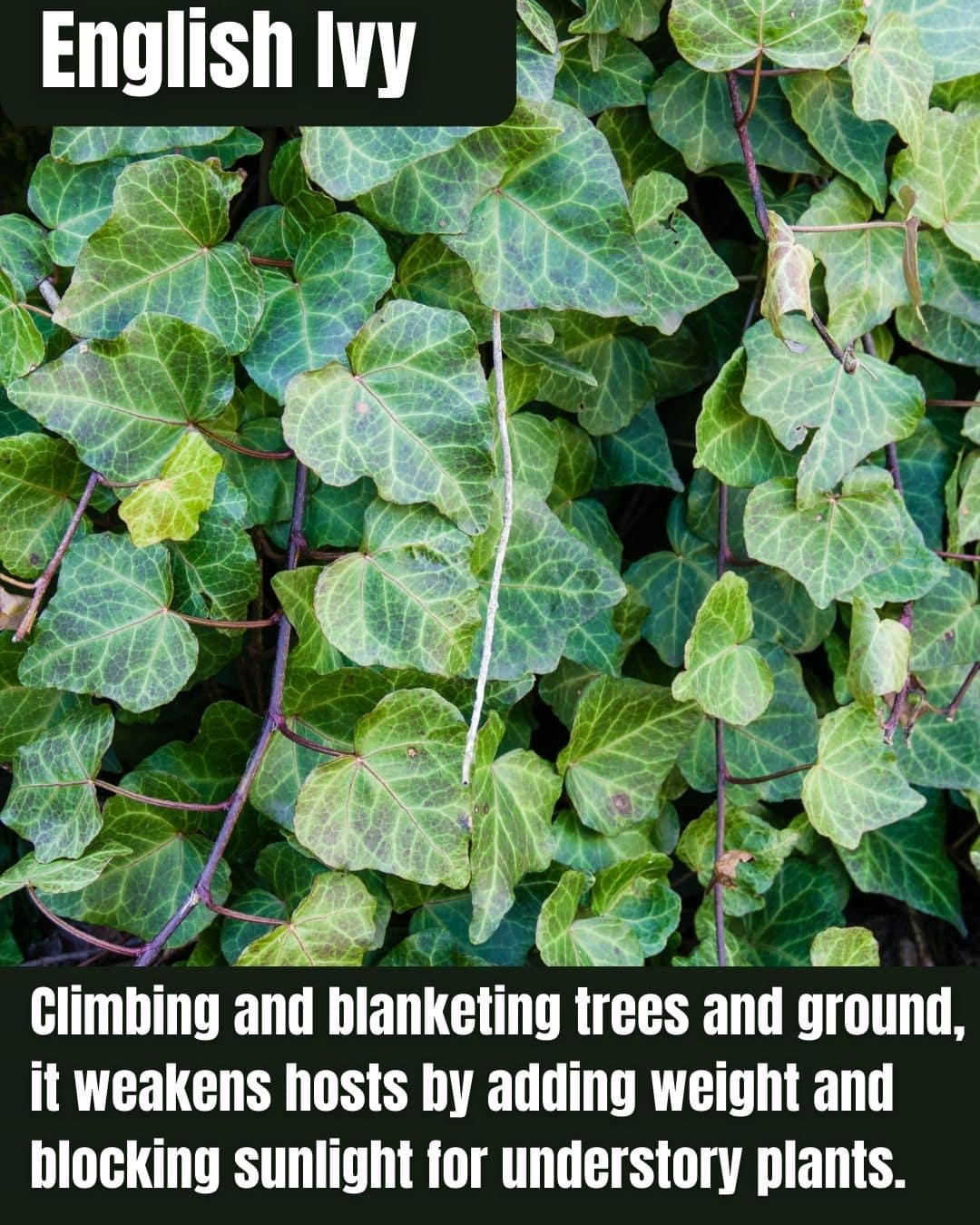

10. English Ivy (Hedera helix)

- Prospers in NJ’s shaded understories, spreading via runners and bird-dispersed berries.

- Interesting fact: Hosts bacterial leaf scorch, harming natives like oaks in NJ.

- Weakens trees by competition for resources, common in urban NJ areas.

English Ivy, a European vine introduced by colonists, overruns New Jersey grounds and trees, displacing natives and killing hosts in forests and yards.

Evergreen leaves form mats, reducing diversity. In NJ, it’s invasive statewide, climbing up to 90 feet in places like Princeton.

Tolerant of shade and poor soils, it regenerates from fragments. Removal by cutting at base and pulling; herbicides for large areas.

Valued ornamentally, but experts urge natives like Virginia creeper to avoid ecological damage.

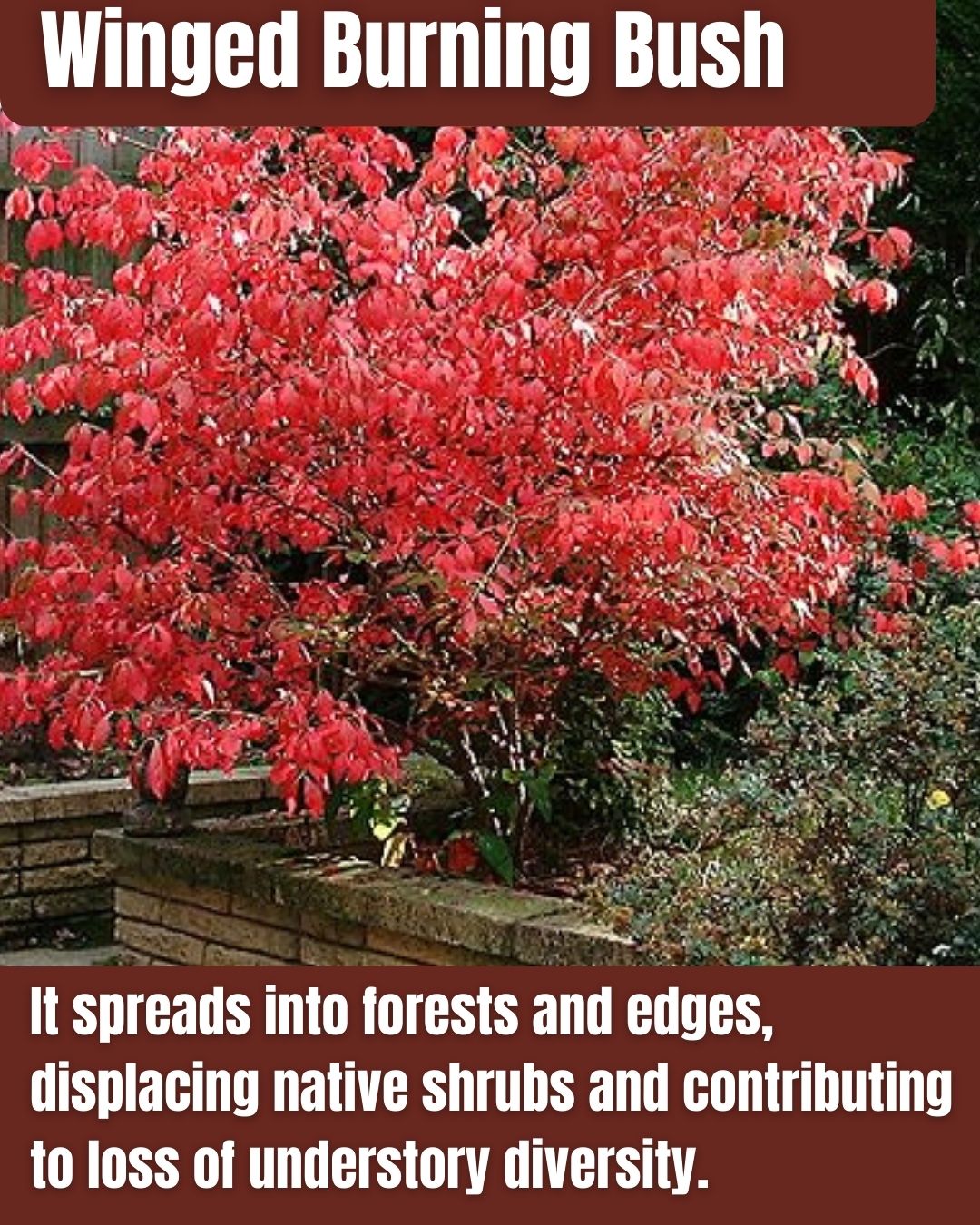

11. Winged Burning Bush (Euonymus alatus)

- Excels in NJ’s full sun to shade, preferring moist soils but adapting widely.

- Interesting fact: Corky wings on stems aid identification; dense stands block light.

- Escapes landscaping to invade woodlands, moderately invasive in NJ.

Winged Burning Bush, an Asian shrub introduced in the 1860s for ornamentals, invades New Jersey edges and forests, forming thickets that reduce native shrubs.

Brilliant fall color attracts gardeners, but fruits are spread by birds. In NJ, it’s widespread in the suburbs, altering habitats in the Sourlands.

Tolerant of varied conditions, it outcompetes post-disturbance.

Control by uprooting young plants or cutting with herbicides; bans in nearby states highlight risks. Native alternatives like highbush blueberry provide similar appeal without invasion.

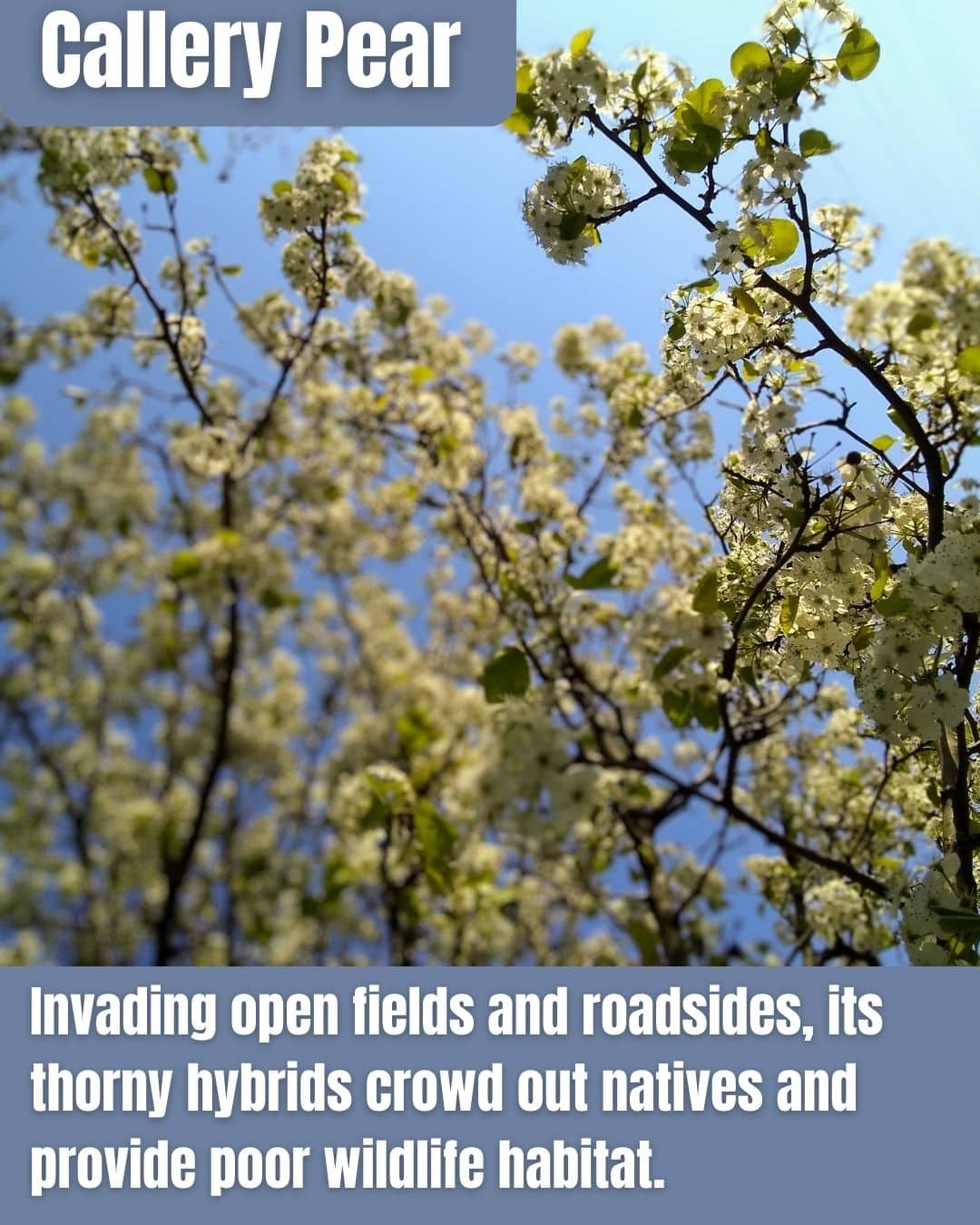

12. Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana)

- Thrives in NJ’s urban tolerances to drought, pollution, and heat, spreading via wildlife.

- Interesting fact: Offensive odor from flowers; banned in NJ and nearby states.

- Forms dense thickets from escaped cultivars, invasive in 25 states including NJ.

The Callery Pear, an Asian tree introduced in the 1900s for fire blight resistance, now invades New Jersey fields and roadsides with thorny hybrids outcompeting natives.

White blooms emit foul smells, fruits litter sidewalks. In NJ, it’s problematic in Montgomery, reducing wildlife value.

Fast-growing to 40 feet, it adapts widely. Control by cutting and treating stumps; removal encouraged under ordinances.

13. Spotted Lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula)

- Feeds on over 70 hosts in NJ, preferring Tree of Heaven for reproduction.

- Interesting fact: Quarantined in NJ counties; damages grapes and trees economically.

- Hitchhikes on vehicles, thriving in temperate climates since 2018 arrival.

The Spotted Lanternfly, an Asian planthopper detected in NJ in 2018, threatens agriculture by feeding on sap, weakening plants and promoting sooty mold.

Colorful adults jump far, and eggs overwinter on surfaces. In NJ, it’s established statewide, hitting vineyards in Warren County.

Tolerant of varied hosts, it spreads via human transport. Control includes scraping eggs and insecticides; public stomping campaigns help.

14. Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis)

- Kills 99% of NJ ash trees, spreading via flight and firewood transport.

- Interesting fact: Larvae destroy vital tissues, killing trees in 2 years.

- Thrives in NJ’s 24.7 million ash trees, detected since 2014.

The Emerald Ash Borer, an Asian beetle introduced via wood packing, decimates New Jersey ash populations, causing widespread dieback in forests and streets.

Metallic green adults emerge in summer, larvae feed under bark. In NJ, it’s in all counties, killing millions and costing removals.

Strong fliers up to a mile, it infests all ash species. Control via insecticides for valued trees or biocontrol wasps; quarantines limit spread.

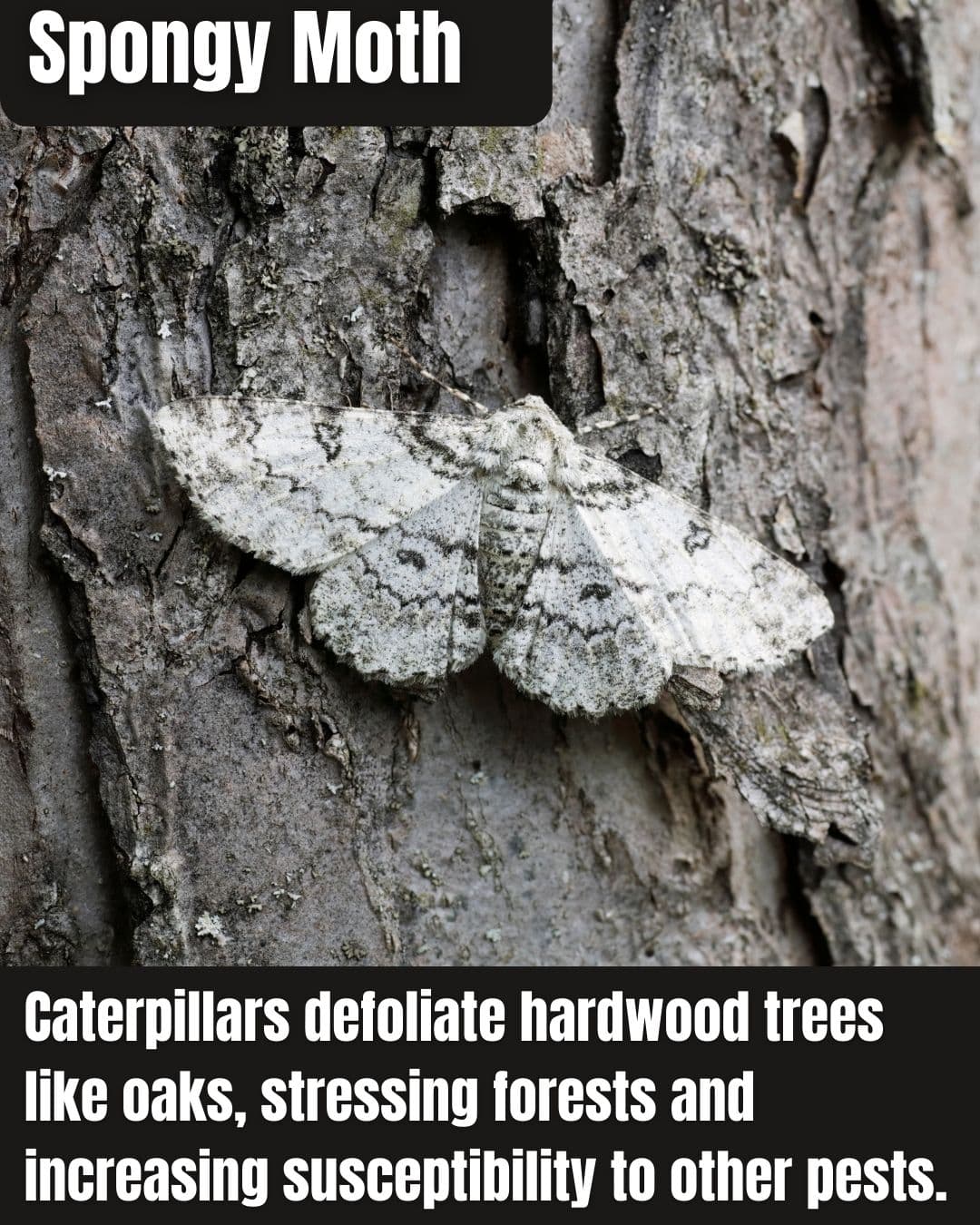

15. Spongy Moth (Lymantria dispar)

- Cyclic populations thrive in NJ’s hardwood forests, feeding on 300+ species.

- Interesting fact: Egg masses spongy and hairy; defoliates millions of acres.

- Warm, dry weather boosts survival in NJ since 1919 introduction.

The Spongy Moth, a Eurasian pest renamed from gypsy moth, causes periodic defoliation in New Jersey forests, weakening trees to secondary threats.

Caterpillars hatch in spring, adults flightless females lay masses of eggs. It’s destructive statewide, decimating Hopewell oaks.

Outbreaks every 10-15 years, spread via wind and humans.

16. Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Halyomorpha halys)

- Thrives in New Jersey’s temperate climate and diverse crops, overwintering in structures for protection.

- Interesting fact: Causes $37 million in apple losses nationwide, with NJ peaches heavily hit in 2010-2011.

- Aggregates in homes, spreading via trade since 1998 introduction.

The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, an Asian pest first found in NJ around 2004, damages fruits and vegetables by feeding, leading to deformities and mold.

Adults release odors when threatened, becoming a nuisance indoors. In NJ, it’s widespread in farms like those in Warren County, impacting soybeans and orchards.

Tolerant of varied hosts, it hitchhikes on shipments. Management includes traps, nets, and biocontrol wasps.

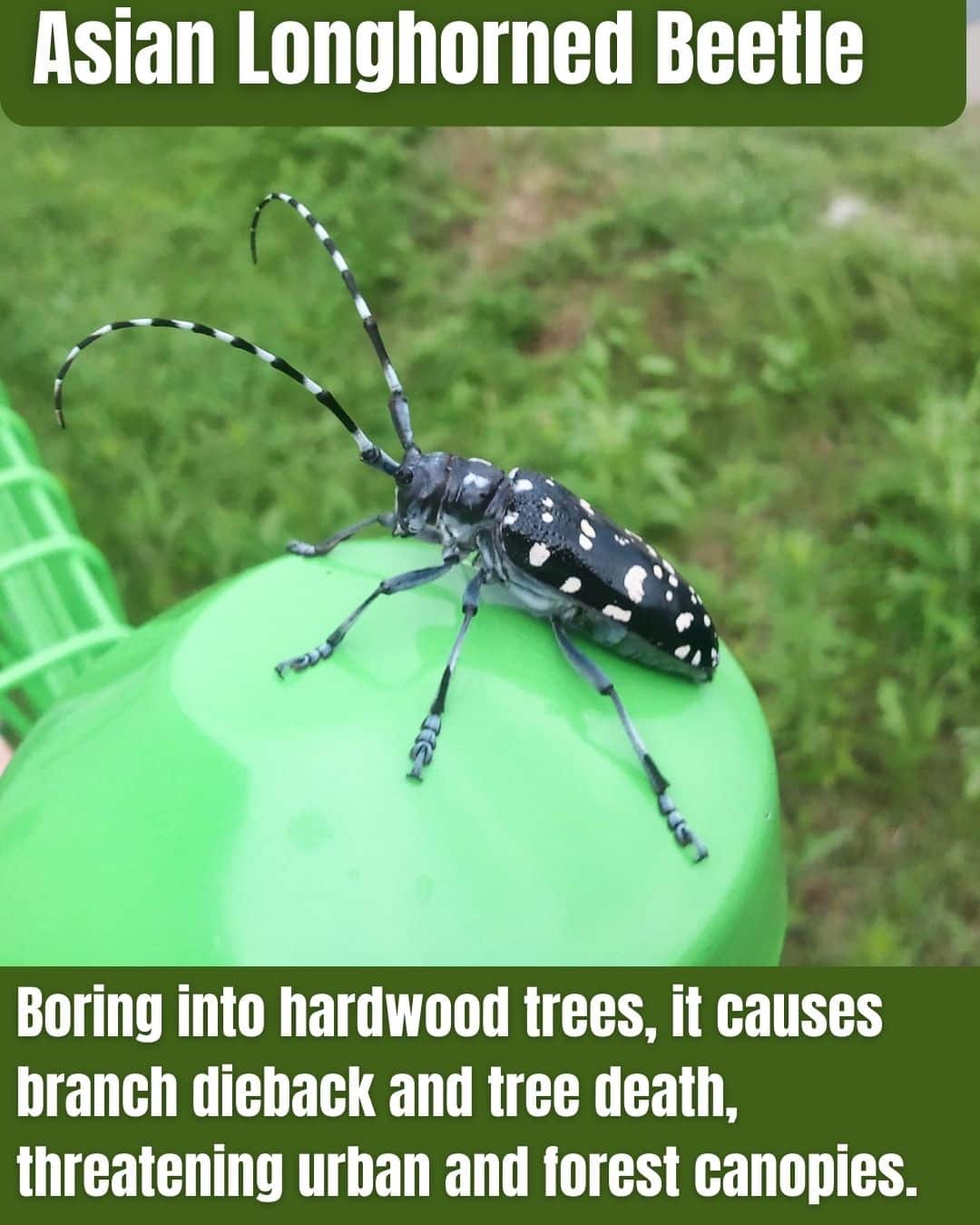

17. Asian Longhorned Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis)

- Succeeds in NJ’s hardwood areas, though eradicated in 2013 after 2002 detection.

- Interesting fact: Larvae kill trees by disrupting sap flow, leading to 21,981 removals in NJ.

- Spreads via infested wood, targeting maples and elms in urban settings.

The Asian Longhorned Beetle, an Asian invader via wood packing, threatened NJ hardwoods by boring, causing dieback.

Black-and-white adults emerge every summer, laying eggs in pits. In NJ, outbreaks in Middlesex and Union counties prompted quarantines and tree removals, and they were declared eradicated in 2013.

Strong fliers; they infest healthy trees. Vigilance includes reporting oval exit holes; firewood bans prevent reintroduction.

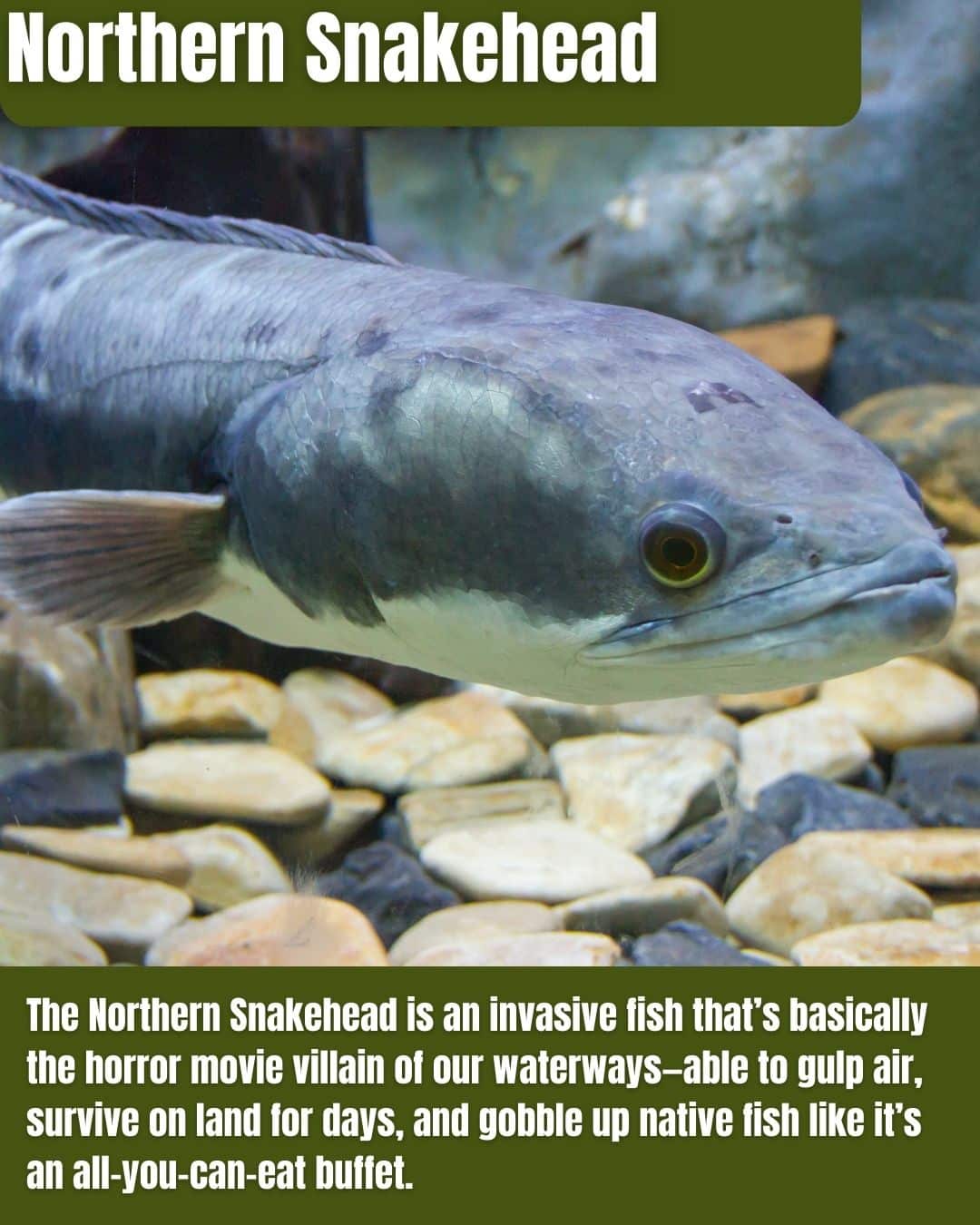

18. Northern Snakehead (Channa argus)

- Flourishes in NJ’s warm, low-oxygen waters, surviving out-of-water for days.

- Interesting fact: Grows to 3 feet, preying on bass and perch in Delaware tributaries since 2009.

- Introduced via releases, aggressive with no predators in NJ.

The Northern Snakehead, an Asian fish that’s banned in NJ, invades rivers by outcompeting natives as top predators.

Oblong bodies and snake-like heads aid ambush. In NJ, it’s established in DOD Ponds and Raritan. Air-breathing allows overland movement.

Policy mandates killing upon catch; some anglers target it with bows.

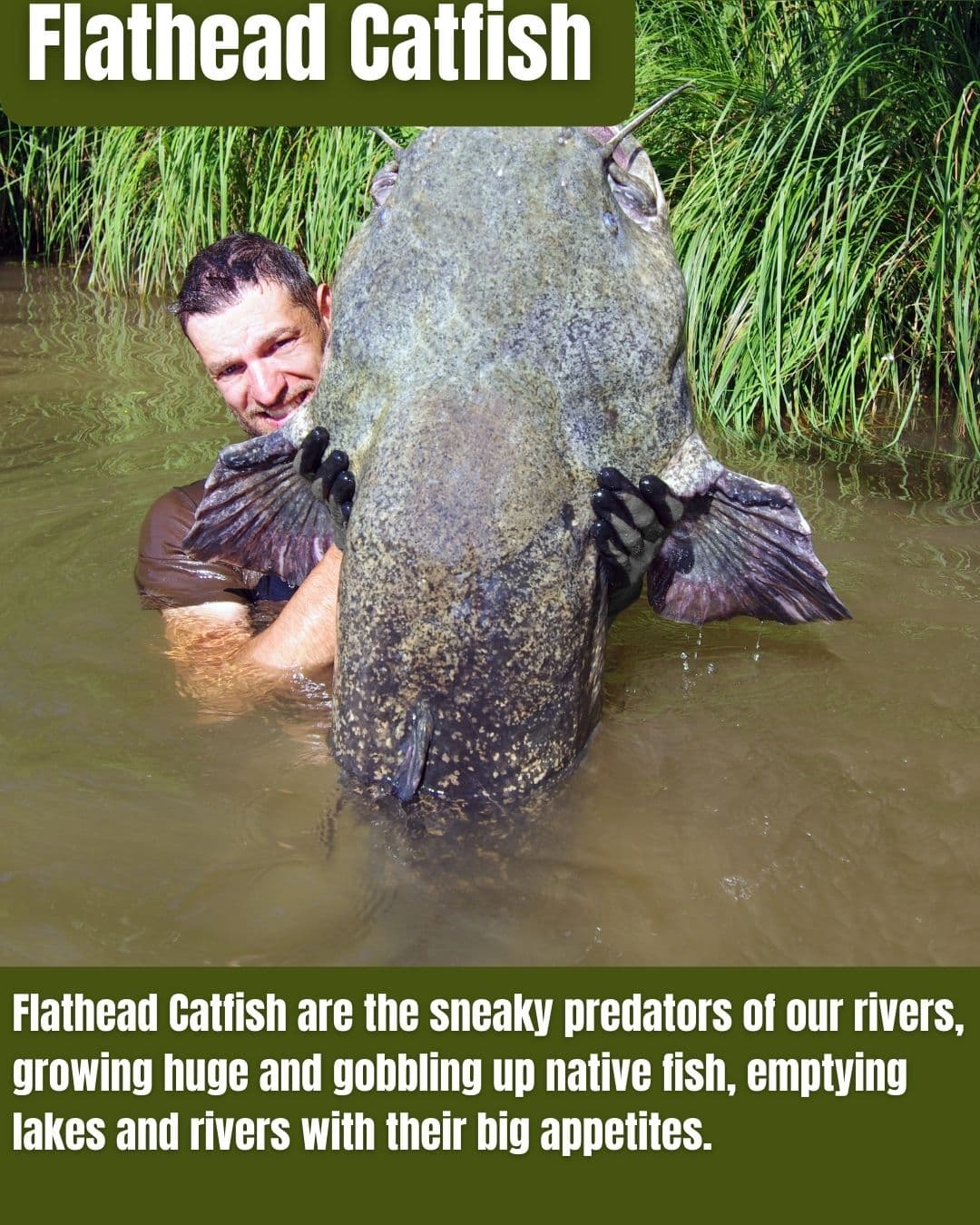

19. Flathead Catfish (Pylodictis olivaris)

- Adapts to NJ’s large rivers like the Delaware, preferring deep pools.

- Grows to over 50 pounds, outcompeting channel cats since 2004.

- Nocturnal ambush predator, spreading via illegal stocking.

Flathead Catfish, native to the Midwest but invasive in NJ, alters ecosystems by preying on natives in rivers.

Flat heads and mottled bodies camouflage. In NJ, they are problematic in the Delaware, reducing sunfish populations.

Tolerant of murky waters, they spread rapidly. Removal is encouraged, and there are no bag limits.

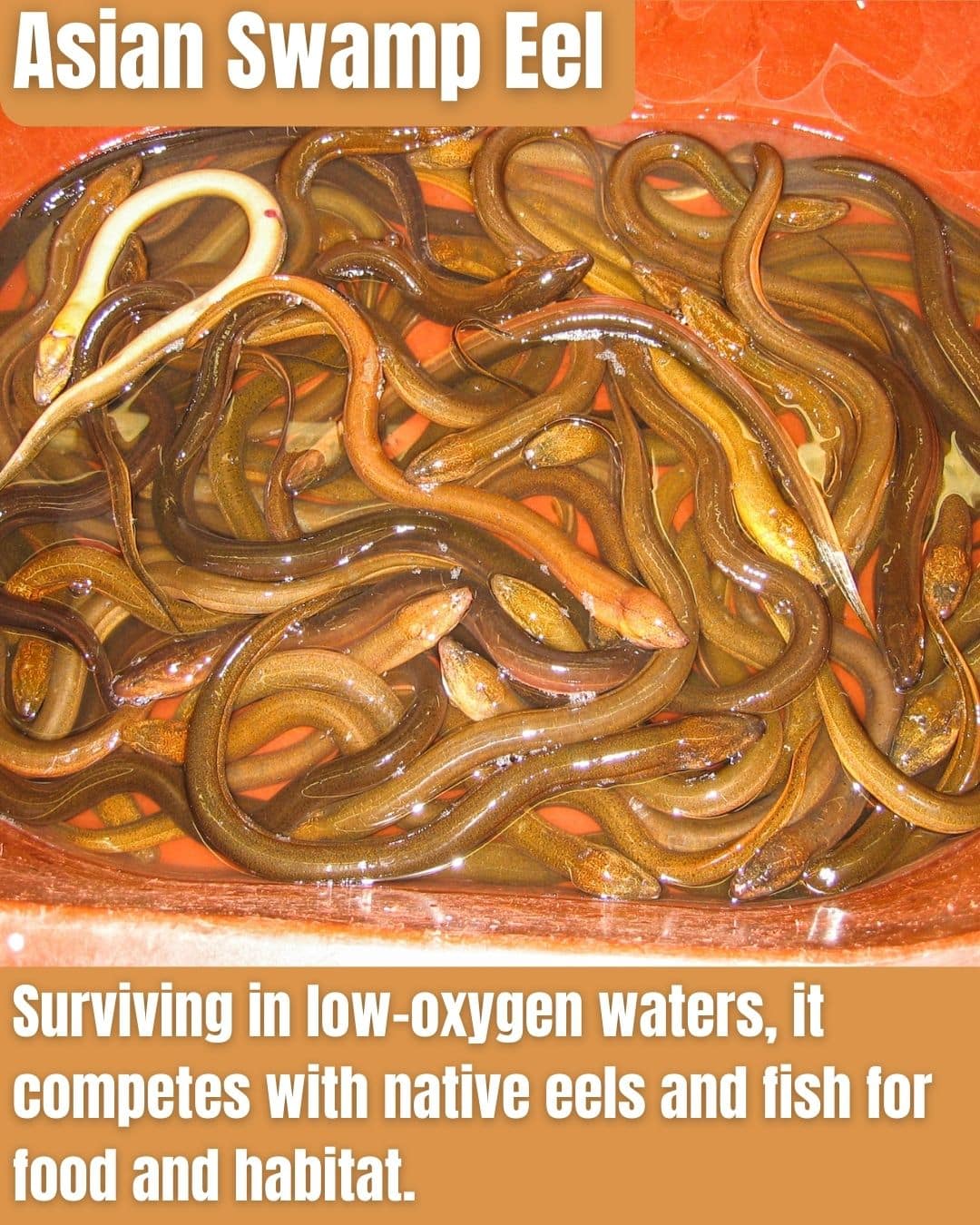

20. Asian Swamp Eel (Monopterus albus)

- Excels in NJ’s polluted, low-oxygen wetlands, burrowing in mud.

- Interesting fact: Hermaphroditic, changing sex; first NJ sighting in 2008 Gibbsboro.

- Competes with natives, potential parasite vector like gnathostomiasis.

Asian Swamp Eel, an Asian import via food trade, invades NJ waters, outcompeting eels and amphibians.

Elongated, finless bodies enable survival in poor conditions. In NJ, established in Silver Lake and southern streams, threatening rare species. Skin-breathing aids drought tolerance.

Prohibited; removal via electrofishing. Risks human health via raw consumption. Monitoring prevents spread.

21. Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus)

This bottom-dwelling bully can be thought of as an egg-eating enforcer that hugs the lake or riverbed, aggressively consuming fish eggs and taking over prime spawning and feeding grounds in rocky, gravel-filled areas.

- Prospers in NJ’s brackish buffers, spreading via ballast since watchlist status.

- Interesting fact: Eats native fish eggs, altering benthics; in Hudson since 2023 studies.

- Aggressive, high reproduction in invaded waters.

The species thrives in New Jersey’s brackish waterways, where fresh and salt water mix, and it has spread largely through ship ballast water.

Because of its rapid expansion and ecological impact, it has been placed on monitoring and watch lists. Studies have confirmed its presence in the Hudson River since 2023.

22. European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

- Adapts to NJ’s urban sprawl, nesting in cavities since 1890 release.

- Murmurations foul areas; displaces woodpeckers statewide.

- Omnivorous, spreads diseases and damages crops.

The European starling was introduced in New York and has since spread aggressively across New Jersey, where it overruns native bird species by forcibly taking over nesting sites and evicting them.

Its glossy, iridescent feathers and bright yellow beak make it easy to recognize. Now widespread, starlings cause significant agricultural damage. Massive flocks can number in the millions.

23. House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)

- Thrives near NJ humans, using buildings for nests since 1850s.

- It destroys the eggs of natives like swallows.

- Prolific breeder, spreads weeds and diseases.

The house sparrow is a Eurasian species that was introduced to North America and now competes aggressively in New Jersey’s urban and suburban areas, where it reduces native songbird diversity.

It is identified by its brown-streaked body and the male’s distinctive black bib. Now widespread, house sparrows dominate feeders and nesting sites.

With no legal protections, removal through trapping is allowed. Providing native bird boxes helps offset losses, though its minor pest-control role remains debated.

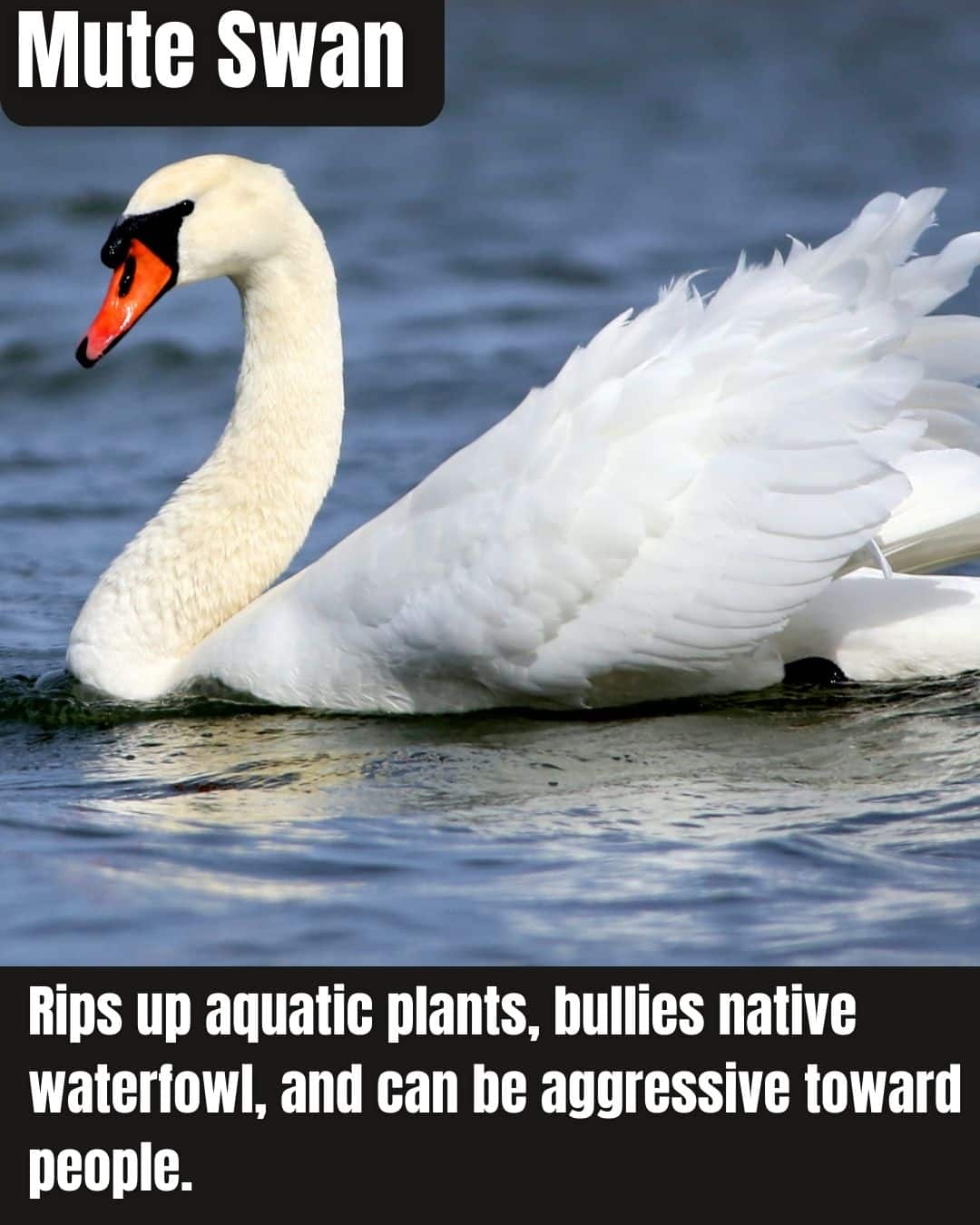

24. Mute Swan (Cygnus olor)

- Dominates NJ wetlands, aggressive year-round since it’s initial release.

- We’re winning the fight: Reduced 56% via culls 2010-2020.

- Overgrazes plants, impacts fish spawning.

The mute swan is a European species that escaped captivity and now invades New Jersey waterways, where it aggressively displaces native ducks and other waterfowl.

Its long, curved neck and bright orange bill make it easy to recognize. Classified as a high-threat invasive species, its population is managed through controlled removals.

In places like Greenwood Lake, mute swans have caused serious disruption. Permits are required for removal, fueling debate over beauty versus ecological harm.

25. Feral Cat (Felis domesticus)

- Persists in NJ’s urban-rural mix, high reproduction without controls.

- Interesting fact: Kills billions of birds yearly; TNR debated.

- Vectors diseases like toxoplasmosis.

Feral cats are descendants of domesticated cats that now live and hunt independently, and they pose a serious threat to New Jersey wildlife by heavily preying on native species, especially songbirds.

With varied coat colors and mostly nocturnal habits, they are efficient hunters.

Established colonies, such as those documented in Lawnside, have measurable impacts on local wildlife. Trap-neuter-return programs, including efforts in Red Bank, aim to control populations, while education campaigns encourage keeping pets indoors, highlighting the ongoing tension between animal welfare and ecological protection.