You don’t notice invasive species all at once. They don’t crash in loudly. They creep. One strange crab in a trap. One “new” beetle on a backyard tree. One fish that shows up where it has no business being.

In Washington State, these quiet invasions hit from every angle—Puget Sound shorelines, Columbia Basin canals, mountain trailheads, apple orchards, berry fields, city street trees, and the places your kids (and dogs) run around without thinking twice.

Some invaders erase nursery habitat for salmon. Others wreck shellfish beds, chew through lawns, wipe out trees, or turn a normal weekend boat launch into a “Clean, Drain, Dry” emergency.

Below are 25 invasive creatures causing real damage across Washington—what they do here, why they matter, and the one mistake that helps each one spread (usually without anyone realizing).

Water Invaders: The Ones That Change Entire Lakes, Rivers, and Shorelines

If Washington has a “front line” for invasives, it’s the water. Once a hitchhiker gets into a bay, a lake, or a river system, it doesn’t just move—it multiplies. And then everything downstream pays the bill.

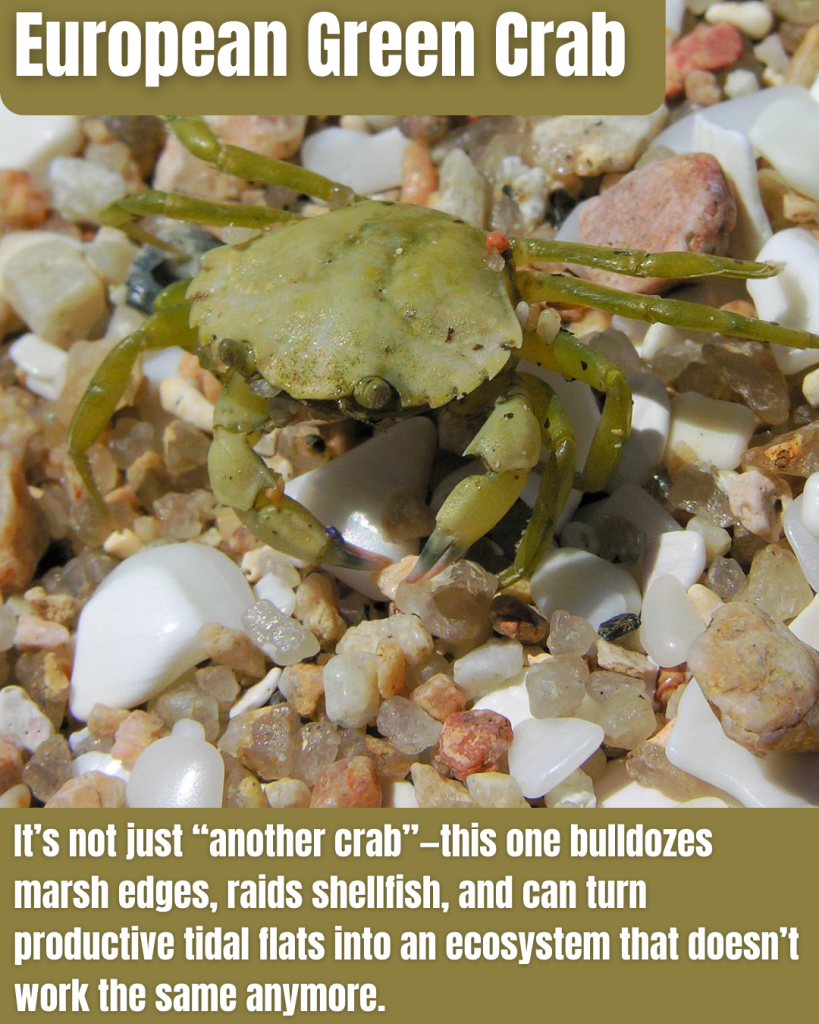

1. European Green Crab (Carcinus maenas)

- Eelgrass destroyer: Tears up eelgrass beds and marsh habitat that protect young fish and stabilize shorelines.

- Shellfish threat: Damages shellfish aquaculture and preys on native clams and crabs.

- Food web wrecker: A proven global invader that reshapes coastal ecosystems once it gains ground.

This crab doesn’t just “show up.” It moves in like a demolition crew.

In Washington’s coastal waters, European green crabs can shred eelgrass beds—the underwater meadows that shelter juvenile fish and support the whole nearshore machine.

The easiest way people help? Moving gear between bays without thinking. If you’re clamming, crabbing, kayaking, or working shellfish areas, treat mud and seaweed like it’s contaminated. Clean it off before you leave.

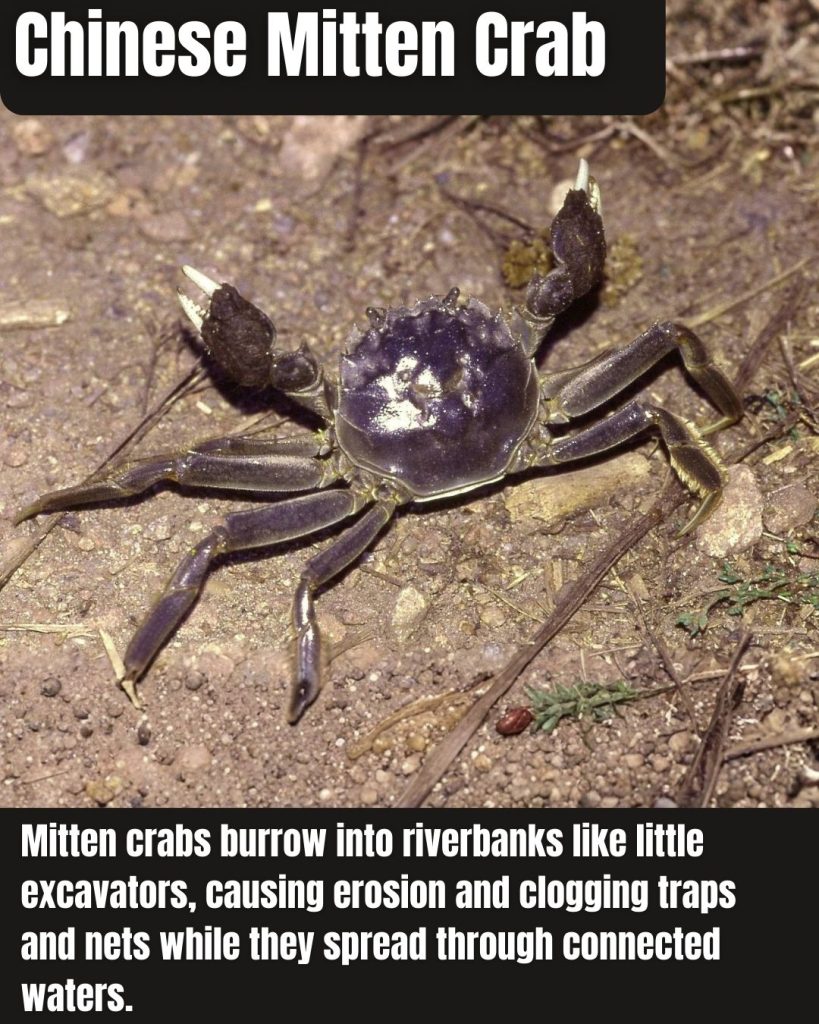

2. Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis)

- Bank burrower: Digs into riverbanks and levees, increasing erosion and collapse risk.

- Fisheries interference: Gets into nets and traps and competes with native species.

- Perfect hitchhiker: Moves through connected waterways and can spread with water movement and human activity.

Mitten crabs are the kind of invader that makes engineers and fishermen lose sleep.

They burrow into banks like living augers, weakening shorelines and making erosion worse—especially in places already pressured by floods and high flows.

The classic spread mistake is moving water, bait, or live aquatic organisms between systems. If you fish multiple waters, keep your bait rules tight and your equipment cleaner than you think you need to.

3. Rusty Crayfish (Faxonius rusticus)

- Native bully: Outcompetes and displaces native crayfish.

- Habitat changer: Chews down aquatic vegetation and shifts stream and lake structure.

- Spreads via bait: One of the most common “oops” pathways is dumping live bait.

Rusty crayfish don’t look dramatic, which is why they slip in under the radar. But once established, they can strip plants, shove out native crayfish, and change what small fish and insects can survive in that water.

If you want the one rule that matters most: never release live bait. Not “back into the water,” not “just in the weeds,” not “it’s only a few.” That’s how invasives become permanent.

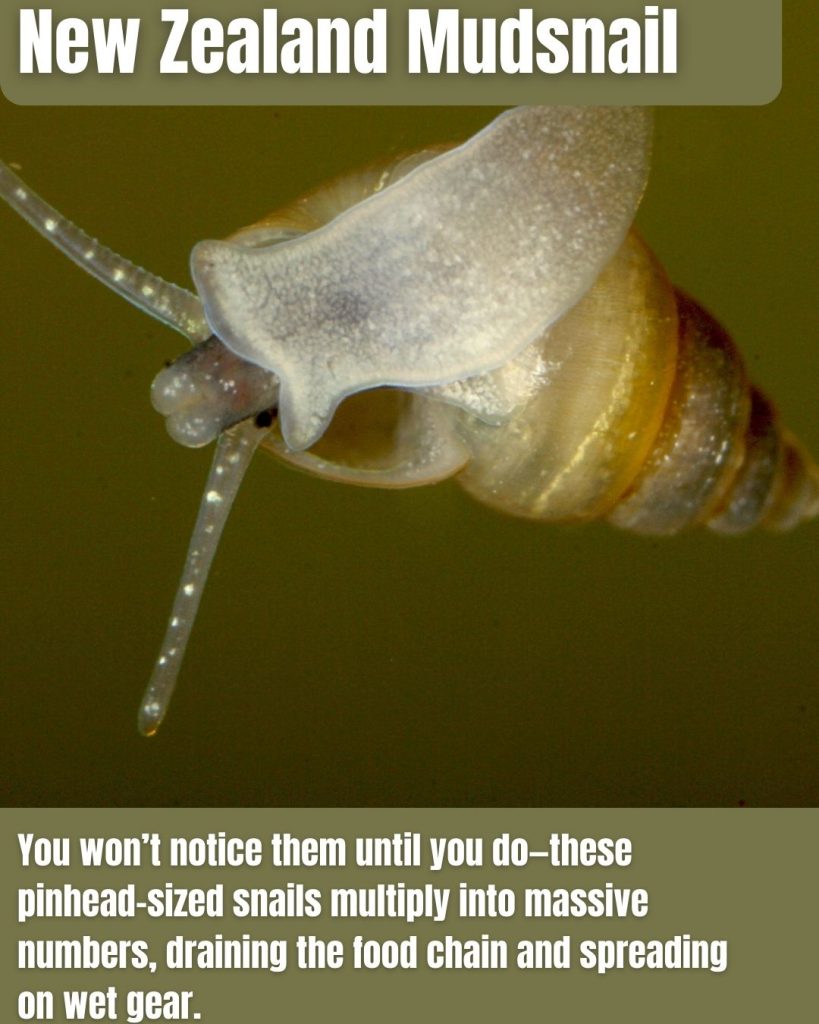

4. New Zealand Mudsnail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum)

- Food thief: Can consume a huge share of stream food, starving native insects that fish depend on.

- Hard to notice: Tiny size makes it easy to spread on waders, boots, nets, and dogs.

- Fast spreader: Once a river or creek gets seeded, it can become a long-term problem.

This is one of the sneakiest invaders on the list because it’s small enough to hide in a boot tread.

Mudsnails can pile up in insane numbers and vacuum up the food that native aquatic insects need—then trout and salmon feel it next.

The spread mistake is simple: walking out of one stream and into another with the same wet gear. If you fish or wade, build a habit: rinse, scrub, dry. And if your dog swims, check paws and fur before you move on.

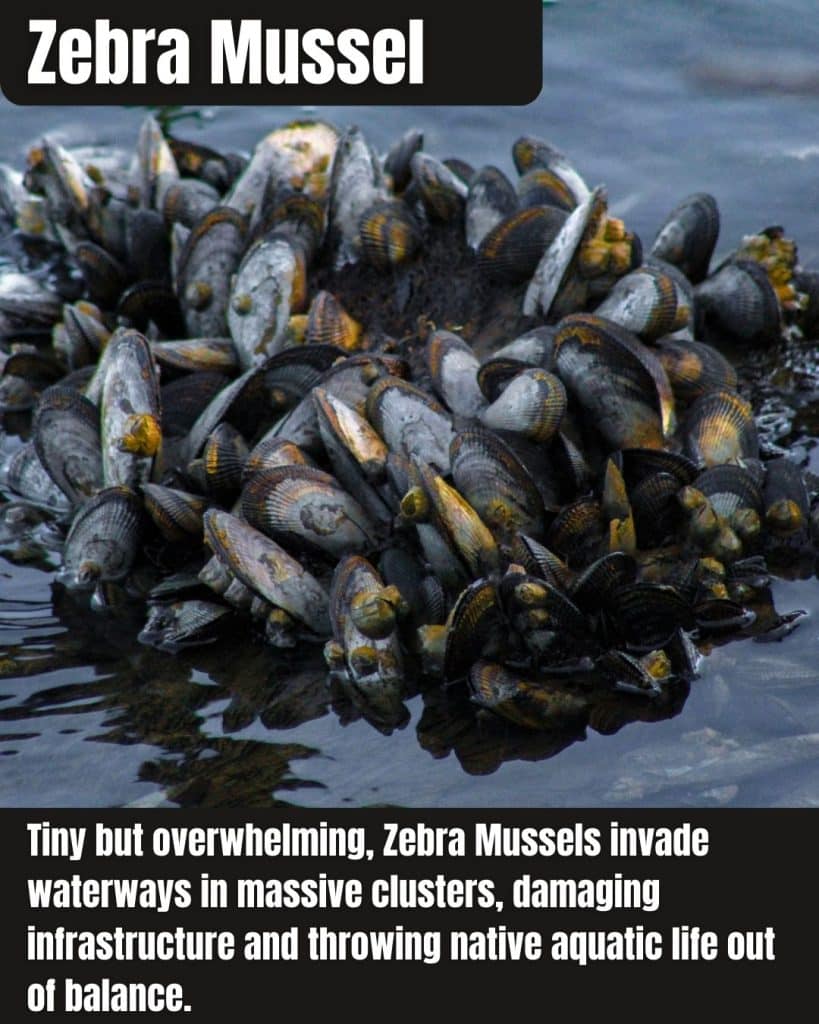

5. Zebra and Quagga Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha and D. bugensis)

- Clogs infrastructure: Pipes, intake screens, irrigation systems, and marina equipment can get packed with shells.

- Smothers natives: They attach in piles, stressing or killing native mussels and changing habitat.

- Spreads on boats: Water in bilges/livewells and wet gear can move larvae between lakes.

Washington has worked hard to keep zebra and quagga mussels from becoming “the new normal,” because once they get established, the costs don’t stop.

They clog systems, coat hard surfaces, and can reshape water quality by filtering the life out of the water column.

The spread mistake is always the same: moving a wet boat or wet gear. If you trailer, the gold standard is Clean, Drain, Dry. If you’re in a hurry, that’s exactly when you’re most likely to transport trouble.

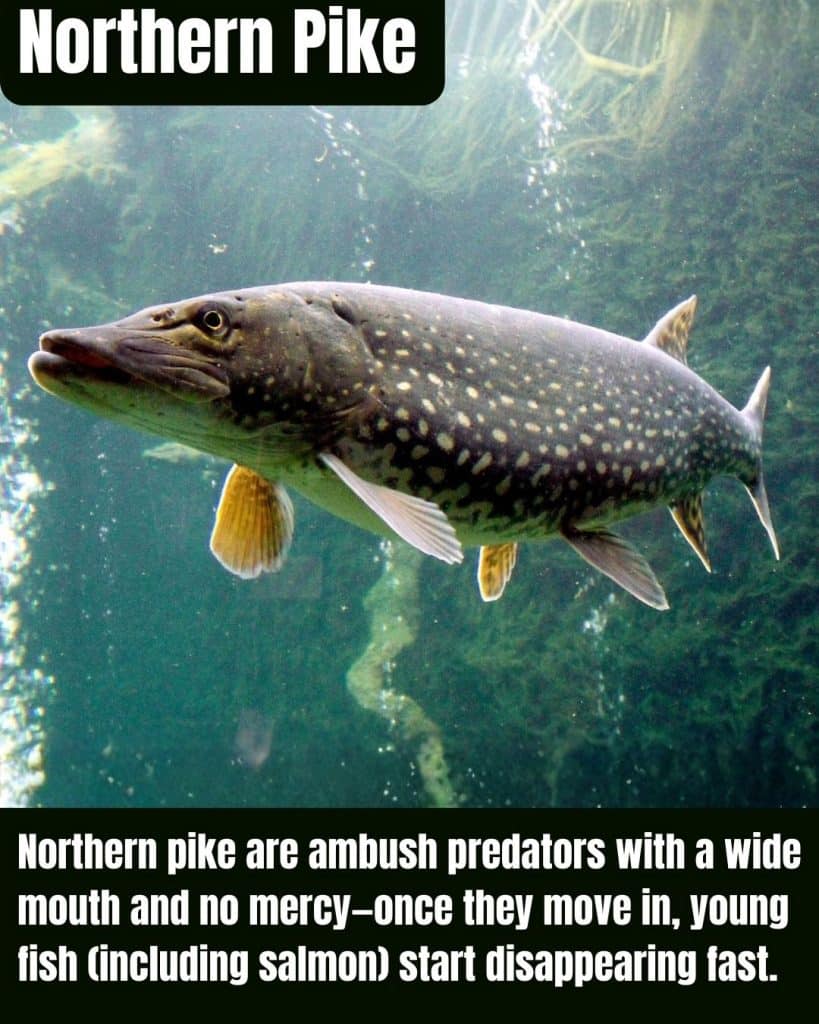

6. Northern Pike (Esox lucius)

- Ambush predator: Eats smaller fish, including salmon juveniles and native species.

- Food web disruptor: Can change entire fish communities once established.

- Human-assisted spread: Illegal stocking and moving live fish are the big pathways.

Northern pike are built like underwater mousetraps—quiet, patient, and brutally effective.

In waters that are supposed to raise salmon and native fish, pike create a constant predation pressure that the system wasn’t designed to handle.

The spread mistake isn’t subtle: people move fish. If you hear talk of “improving the fishing” by stocking predators, that’s the kind of decision that can wreck a river for decades.

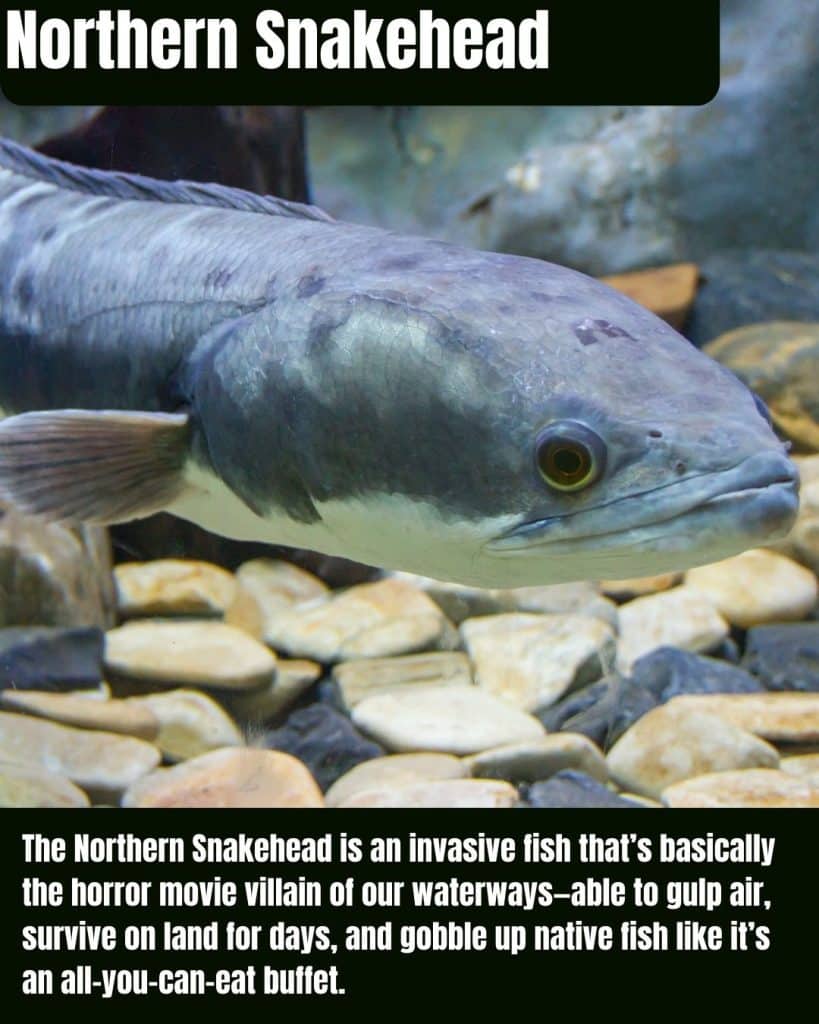

7. Northern Snakehead (Channa argus)

- Voracious predator: Outcompetes and eats native fish and amphibians.

- Tough survivor: Tolerates low-oxygen water and stressful conditions better than many natives.

- Illegal possession risk: “Keeping one alive” or moving one is exactly how invasions start.

Snakehead stories always sound like a tall tale—until you remember how many invasions started with somebody thinking it would be “cool” to have a new fish in a pond or a ditch.

The danger isn’t just the fish. It’s the idea that moving it is harmless.

If a snakehead ever shows up in Washington waters, the right move isn’t a social media post first. Document it safely and report it through the proper state channels so it doesn’t become a permanent headline.

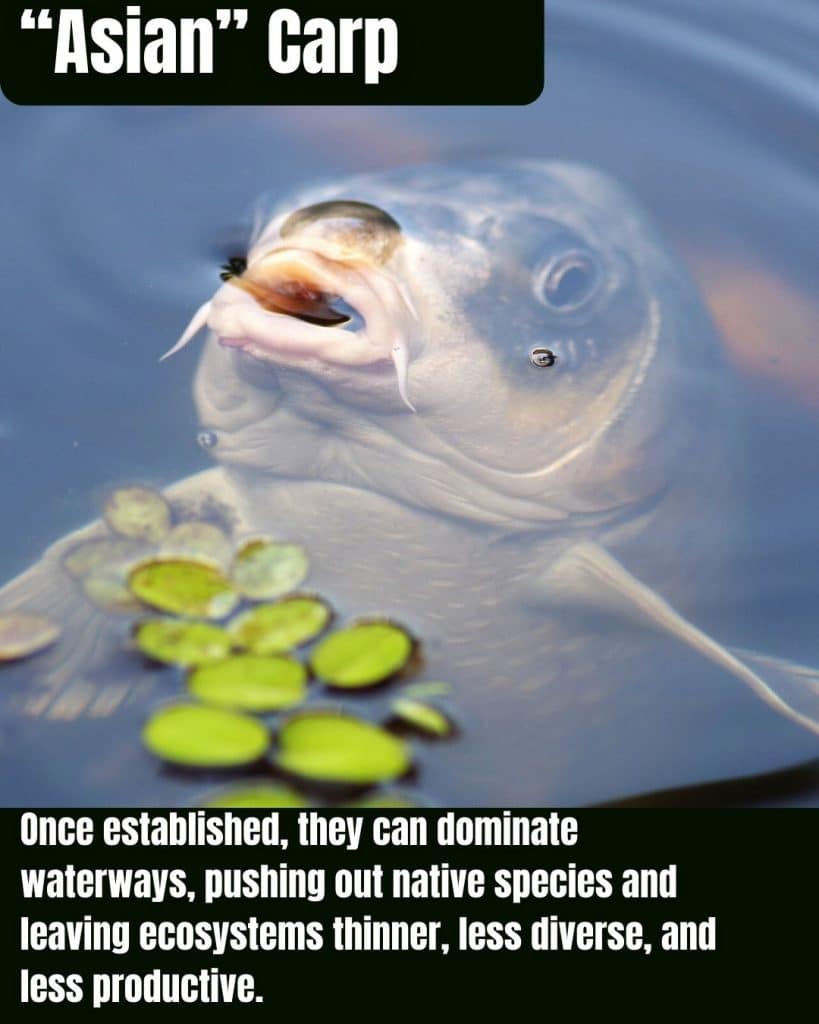

8. Asian Carp (Hypophthalmichthys spp.)

- Plankton vacuum: Filters the base of the food chain, starving native fish and young salmonids.

- Ecological takeover: Can dominate waterways and push out native species.

- Spread via movement: Moving live fish or water is a major pathway.

Carp aren’t “just another fish.” These species can strip a waterway’s pantry by filtering out the plankton that everything else depends on. When the base collapses, the rest of the food web follows—slowly, then all at once.

The spread mistake is usually human convenience: transporting water, moving live fish, or ignoring rules meant to keep waters separated. Invasive fish don’t need many chances—just one.

9. American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus)

- Native-eater: Eats native frogs, salamanders, small fish, and anything it can swallow.

- Breeds fast: Thrives in ponds and slow water, building big populations.

- Human spread history: Often moves with people through releases and “pond stocking.”

Bullfrogs are basically the linebacker of the frog world, and in Washington they can turn a quiet pond into a native amphibian dead end. They eat aggressively, breed successfully, and tolerate conditions that stress more sensitive native species.

The spread mistake is the old one: releasing animals into “a nicer place.” That good intention has created invasive problems all over the country. If it’s not native to that water, it doesn’t belong there.

10. African Clawed Frog (Xenopus laevis)

- Disease carrier: Can spread pathogens that harm native amphibians.

- Competitive invader: Outcompetes native amphibians in suitable habitats.

- Pet/research release pathway: Escapes and releases are the common “origin story.”

This one is a classic “it started in captivity” invader. African clawed frogs have a track record of surviving where they shouldn’t, competing hard, and potentially moving diseases that native amphibians aren’t prepared to handle.

The spread mistake is painful and predictable: dumping aquarium or lab animals. If you’ve got an unwanted animal, there are responsible surrender options. “Release” isn’t kindness—it’s an ecosystem gamble.

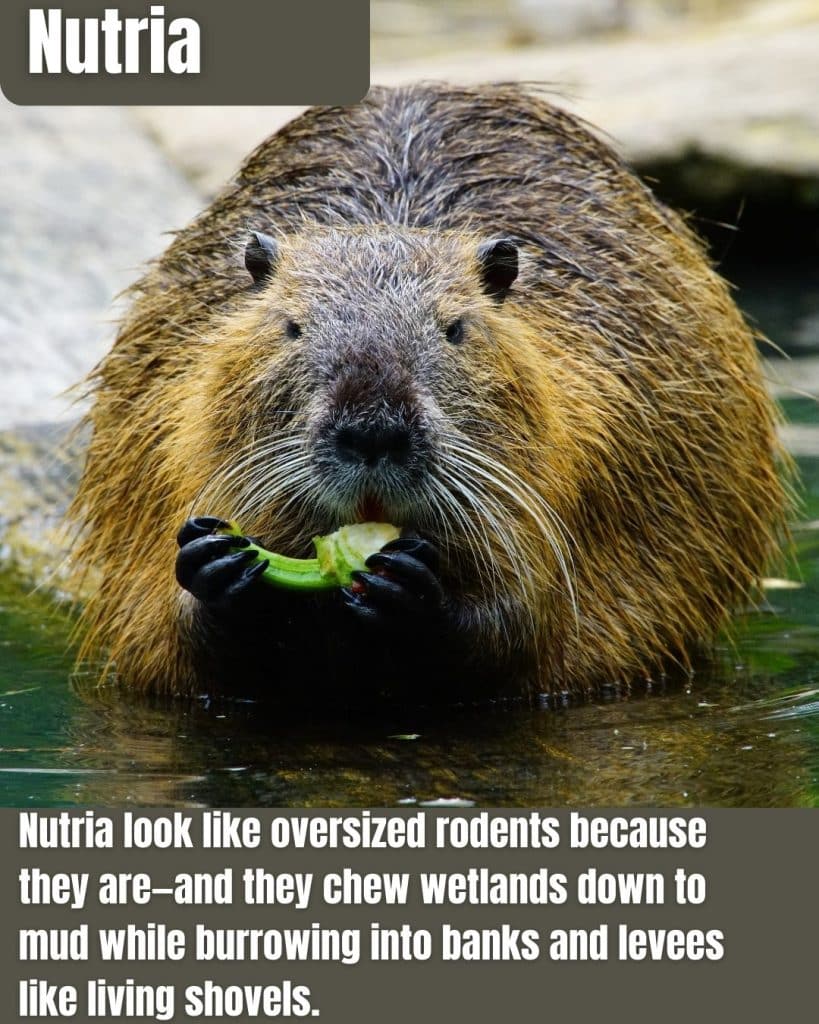

11. Nutria (Myocastor coypus)

- Wetland damage: Eats and uproots vegetation that holds marsh edges together.

- Levee and bank burrowing: Weakens dikes and shorelines through tunneling.

- Hard to notice early: Populations can establish quietly until damage becomes obvious.

Nutria look like a weird mix of beaver and oversized rat, and the damage can be equally confusing at first. But once they dig in, they can chew down wetland plants and undermine banks—turning a stable edge into a collapsing mess.

The spread mistake is usually indirect: moving materials, ignoring sightings, assuming “it’s just one.” With animals that reproduce well, early reporting can save a whole region from a long-term problem.

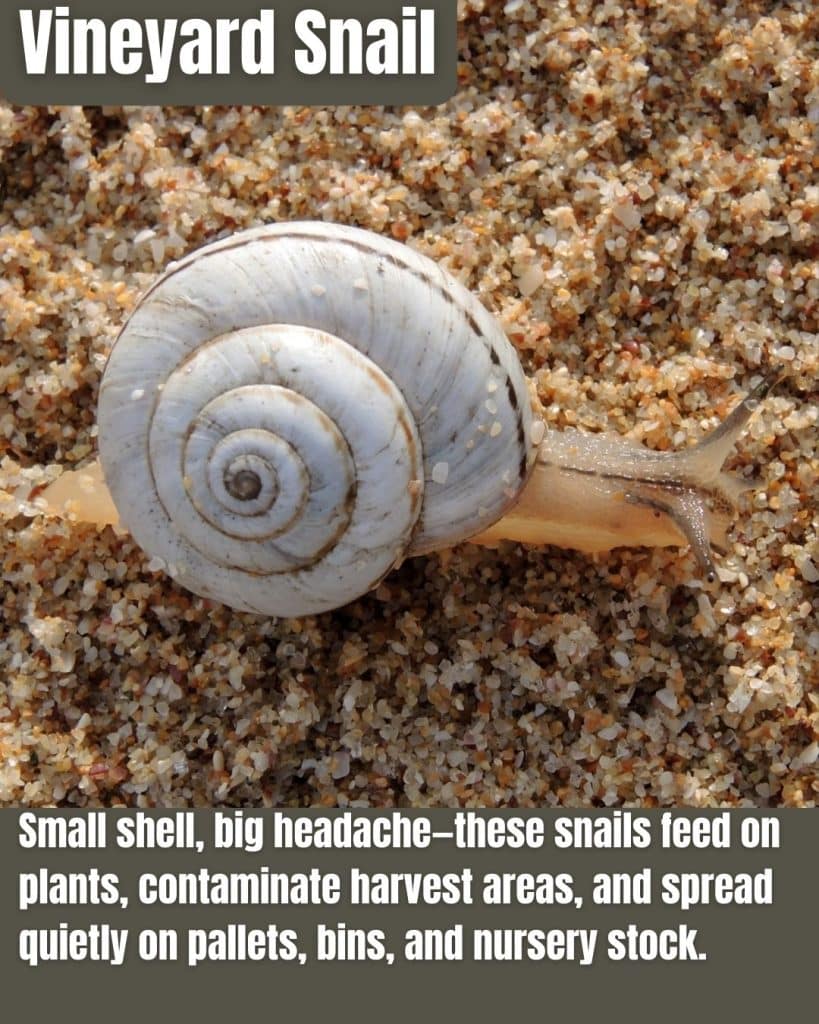

12. Vineyard Snail (Cernuella virgata)

- Crop feeder: Damages plants and creates contamination issues in agricultural settings.

- Trade hitchhiker: Moves with shipments, equipment, and plant material.

- Hard to fully eliminate: Once established, it takes consistent pressure to keep numbers down.

Snails don’t sound scary—until you’re dealing with them in real numbers. Vineyard snails can become an agricultural headache because they don’t just nibble; they contaminate, cluster, and travel with the same commerce that keeps farms running.

The spread mistake is moving infested materials: potted plants, pallets, field equipment, even harvest bins. If something sat in a snail-heavy area, it needs inspection before it goes to a new site.

Land Wreckers: The Big Mammals That Tear Up Ground and Spread Disease

Some invasives don’t need a microscope. They leave obvious sign—rooted-up soil, collapsed banks, shredded lawns, and damage that looks like a rototiller ran wild at 2 a.m.

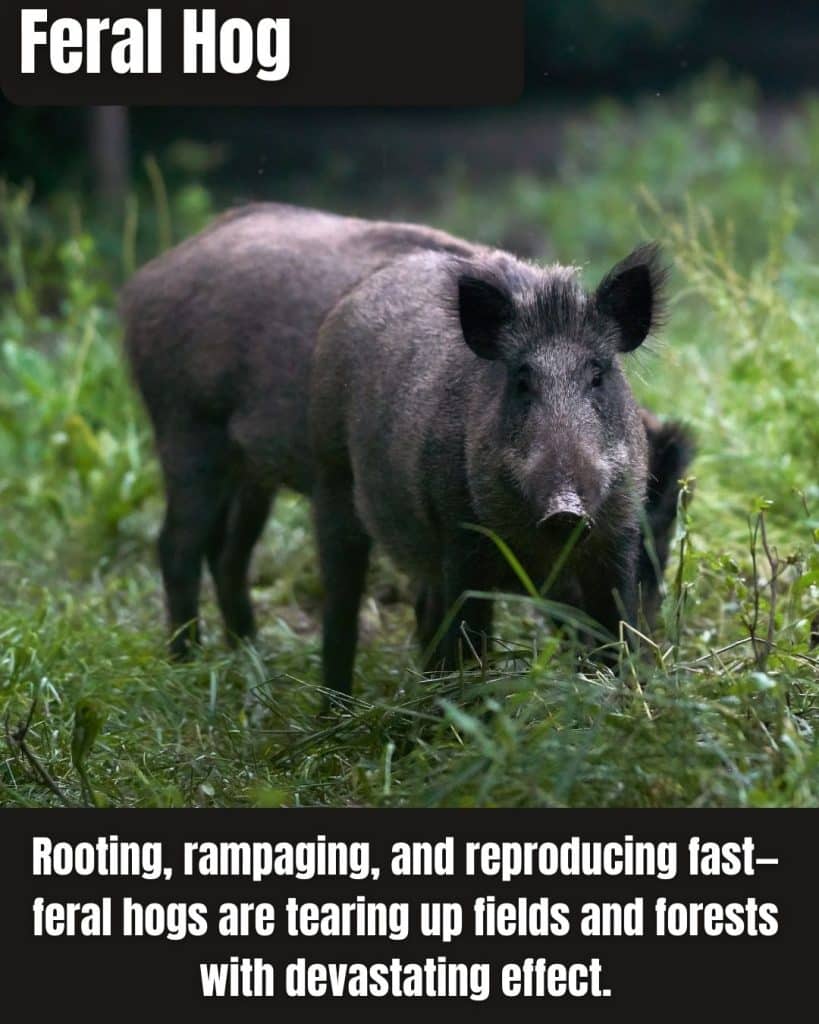

13. Feral Swine (Sus scrofa)

- Soil destroyers: Root up ground like rototillers, damaging forests, fields, and wetlands.

- Crop damage: Tear up farms, food plots, and gardens.

- Disease risk: Can spread diseases that impact livestock, wildlife, and pets.

In Washington, feral swine are treated like what they are: a high-impact threat that’s easier to stop early than to fight later. These animals can tear up ground overnight, create erosion issues, and carry diseases that ripple into farms and wildlife.

The spread mistake is the same story across America: people move pigs, release pigs, or “help” pigs establish for hunting. If you see sign—rooting, tracks, wallows—report it. Waiting is how a sighting becomes a population.

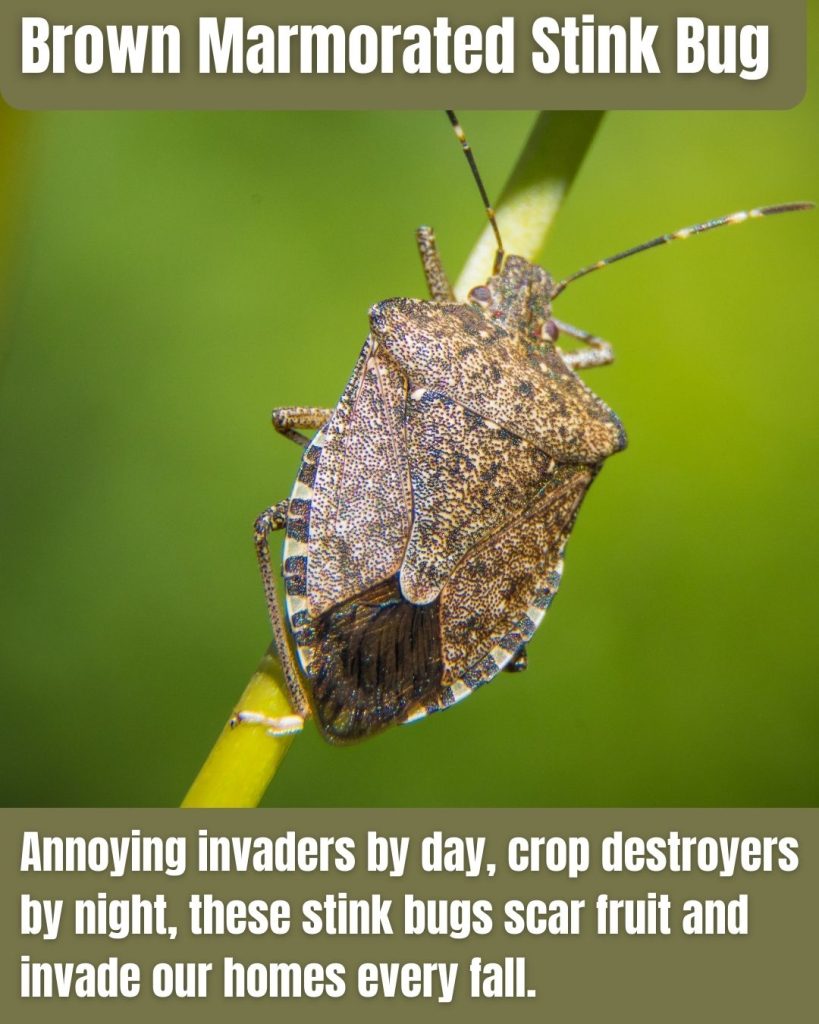

14. Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Halyomorpha halys)

- Crop puncher: Feeds on fruit and vegetables, leaving scars and rot pathways.

- Home invader: Overwinters in houses and buildings by the hundreds.

- Easy to transport: Hitchhikes in vehicles, boxes, firewood piles, and stored items.

This is the bug that turns “weird smell” into “why are there fifty of them on the window?” In Washington’s fruit-growing regions, brown marmorated stink bugs aren’t just annoying—they can damage marketable crops fast.

The spread mistake is accidental travel. They hide in vehicles and storage, then pop out in a new county like they live there. If you’re moving stored goods, outdoor furniture, or equipment, a quick inspection can prevent a fresh outbreak.

Orchard and Garden Hitmen: The Bugs That Turn “A Few Spots” Into Real Money Lost

Washington grows a lot of what the country eats—especially fruit. That also means pests that damage fruit here aren’t just a backyard problem. They’re a statewide economy problem.

15. Apple Maggot (Rhagoletis pomonella)

- Fruit destroyer: Larvae tunnel inside apples and related fruit, ruining quality.

- Spreads via infested fruit: Moving backyard apples is a common pathway.

- Hard to “see” early: By the time you notice, larvae may already be inside the fruit.

The Apple maggot is a nightmare because it’s not loud. A fruit can look fine from the outside, and then you cut it open and realize the damage has already happened. In a state known for apples, that’s not a small issue—it’s personal.

The spread mistake is sharing or transporting homegrown fruit without thinking. If you’ve got backyard apples and you’re traveling, don’t take the fruit with you. Dispose of it properly at home so you don’t seed new areas.

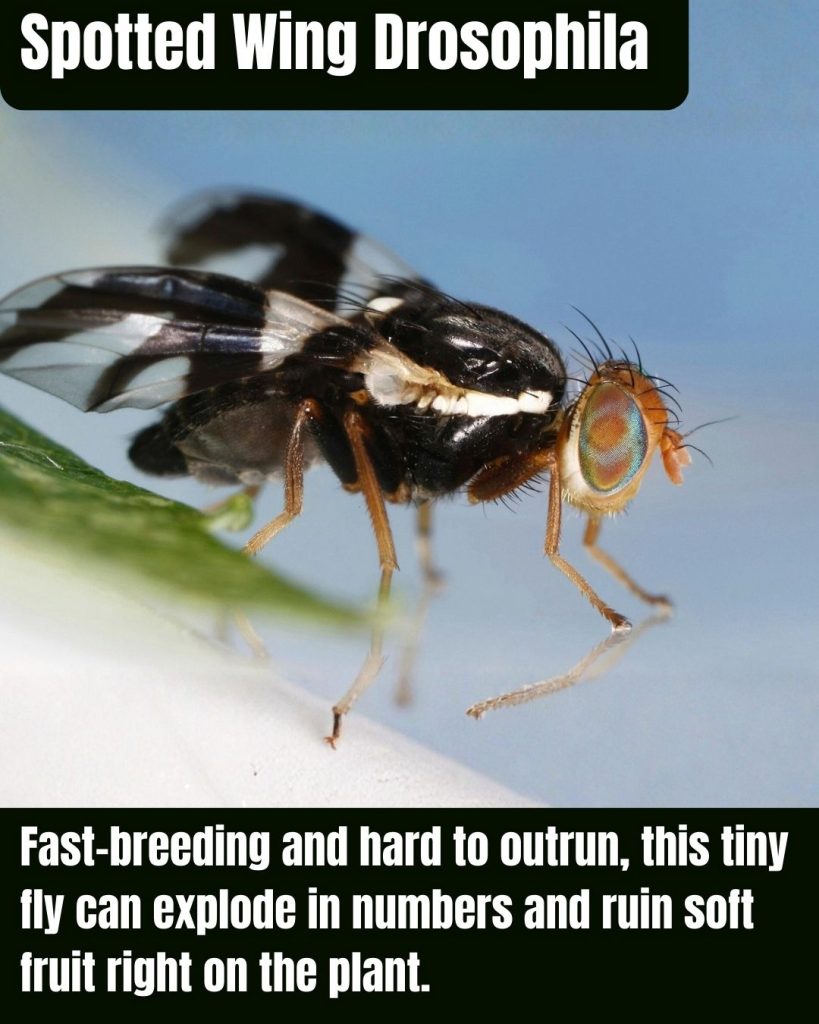

16. Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii)

- Berry attacker: Infests soft fruit like berries, often before harvest.

- Fast reproduction: Populations can explode during the growing season.

- Moves with fruit: Transporting infested fruit spreads it quietly.

This is the “looks fine today, mush tomorrow” pest for berries and soft fruit. Spotted wing drosophila can lay eggs in ripening fruit, and the damage shows up fast—especially in warm stretches.

The spread mistake is moving fruit waste. If you garden, don’t toss infested fruit into open compost piles or along fence lines where flies can keep breeding. Bag it or handle it the way local guidance recommends.

17. European Chafer (Amphimallon majale)

- Grub damage: Larvae chew grass roots, causing dead patches in lawns and turf.

- Soil spread: Moves with sod, soil, and landscaping materials.

- Second-wave problem: Often noticed after animals start digging for grubs.

European chafer is the lawn wrecking ball you don’t see until it’s already working. The grubs chew roots underground, and the first sign is often a lawn that peels up like a rug—or raccoons and skunks digging like they own the place.

The spread mistake is moving sod and soil without checking source risk. Landscaping projects can unintentionally transport grubs to brand-new neighborhoods.

18. Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica)

- Leaf skeletonizer: Adults chew leaves into lace, stressing ornamentals and crops.

- Wide menu: Feeds on many plants, so it spreads damage across landscapes.

- Turf connection: Larvae (grubs) can damage lawns and attract digging animals.

Japanese beetles don’t nibble politely. They show up, recruit their friends, and turn leaves into lace. In Washington, the concern isn’t just what they do to one rose bush—it’s what they can do when they’re entrenched across yards, gardens, and agricultural edges.

The spread mistake is moving infested soil and nursery plants. Adults fly, sure—but grubs travel the easy way: in root balls, sod, and soil that looks harmless.

19. Scarlet Lily Beetle (Lilioceris lilii)

- Lily destroyer: Defoliates lilies and related plants fast.

- Garden heartbreak: Turns prized ornamentals into bare stems in a short window.

- Moves with plants: Nursery stock and plant swaps are common pathways.

If you grow lilies, this beetle feels personal. It can take a plant you’ve babied for years and strip it down like a prank—except it’s not a prank, and it comes back every season if it gets established.

The spread mistake is well-meaning sharing. Plant swaps and “here, take a bulb” gifts are great—unless the plant is carrying eggs or larvae. Inspect plants closely before you move them.

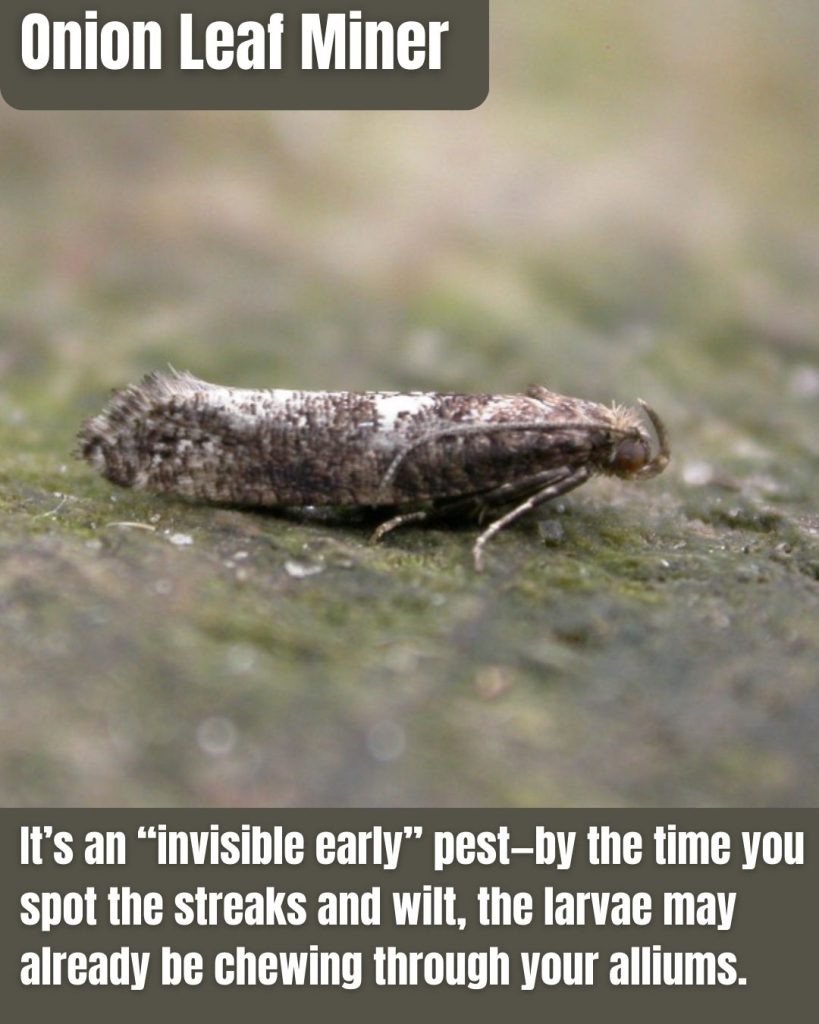

20. Onion Leaf Miner (Phytomyza gymnostoma)

- Allium attacker: Damages onions, garlic, leeks, and related crops.

- Hidden feeding: Larvae mine inside leaves, making early damage easy to miss.

- Moves with plant material: Starts new infestations through transported plants and contaminated debris.

Onion leaf miner is a “quiet” pest with loud consequences. The damage happens inside leaves, so gardeners often notice only after plants stall, yellow, or start collapsing in patches.

The spread mistake is moving allium starts and plant debris between gardens and regions. If you’re sharing garlic or onion starts, be picky about source and keep your cleanup habits tight at the end of the season.

Forest and Street Tree Killers: The Ones That Change a Neighborhood’s Shade

When tree pests get established, the damage doesn’t look like “a bug problem.” It looks like a changed town: fewer healthy trees, more removals, more dead limbs in windstorms, and years of recovery.

21. Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis)

- Fast ash killer: Infestations can kill trees in just a few years.

- Canopy loss: Neighborhoods and forests lose shade and stability.

- Firewood spread: Moving firewood is one of the easiest ways to help it travel.

Emerald ash borer is the tree pest that turns “we’ve got lots of ash” into “we used to have ash.” The larvae tunnel under bark and cut off the tree’s ability to move water and nutrients, and once the decline starts, it can move fast.

The biggest accidental spread in the country is also the easiest one to avoid: don’t move firewood. Buy it where you burn it—even within the same state—because pests don’t care about county lines.

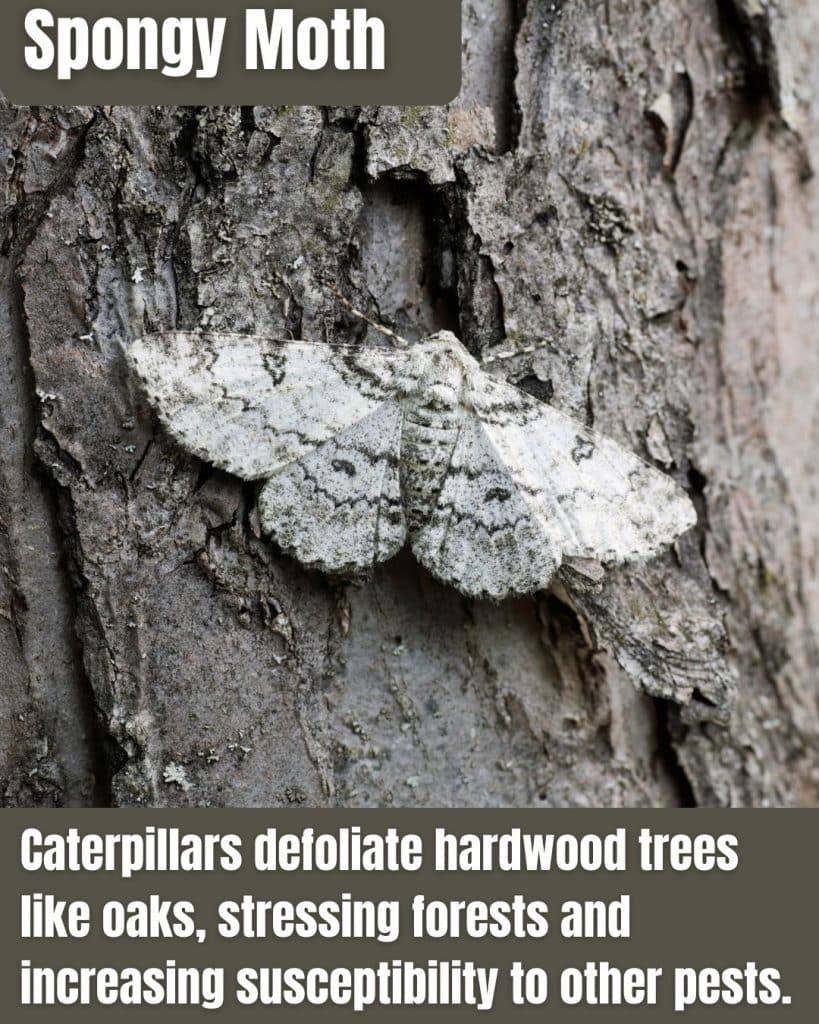

22. Spongy Moth (Lymantria dispar)

- Defoliator: Caterpillars can strip trees, stressing forests and yards.

- Human-transported: Egg masses hitchhike on vehicles, campers, and outdoor equipment.

- Repeat stress: Multiple years of defoliation can weaken trees to the breaking point.

Spongy moth damage can look like a storm hit the canopy—except it’s caterpillars. Defoliation weakens trees, and weak trees invite secondary problems. That’s when the real losses begin: removals, hazards, and long recovery.

The spread mistake is travel. Egg masses can ride on campers, trailers, firewood stacks, and patio furniture. If you’ve been in an infested area, inspect before you bring gear back into Washington forests and neighborhoods.

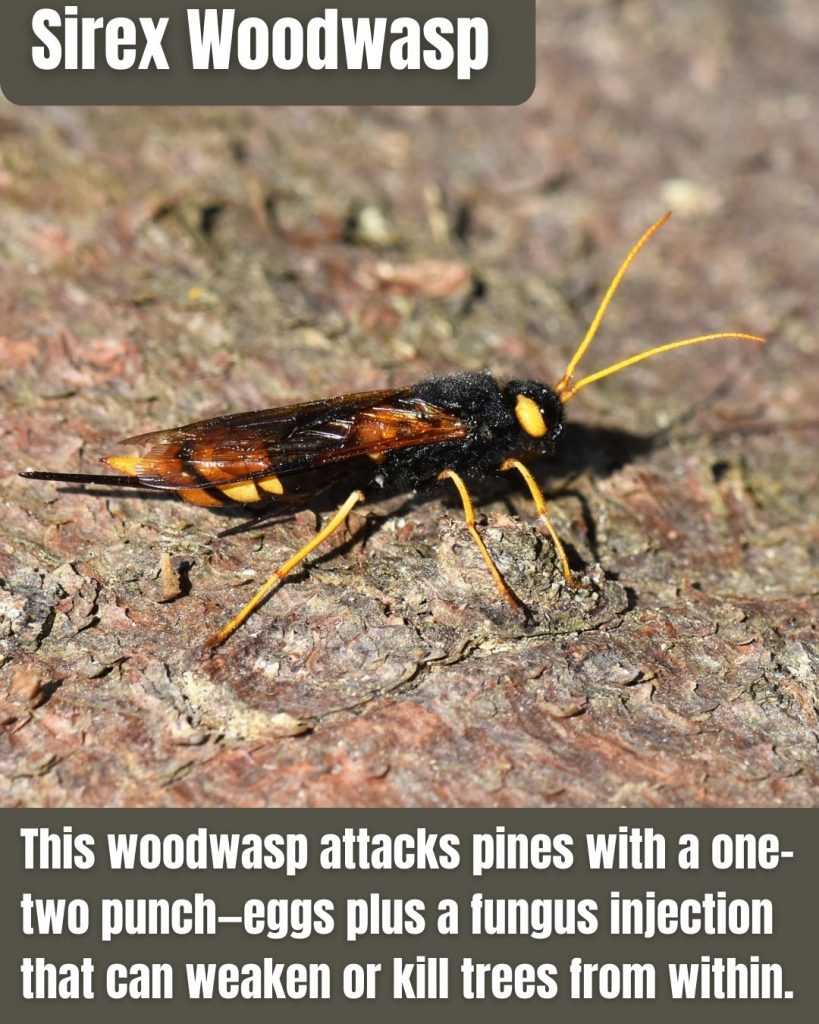

23. Sirex Woodwasp (Sirex noctilio)

- Pine killer mechanism: Injects fungus along with eggs, stressing and killing pines.

- Forestry risk: Threatens pine resources and increases management costs.

- Wood movement pathway: Moves with logs, untreated wood, and related materials.

Sirex woodwasp is the kind of pest foresters watch closely because it doesn’t just “feed on trees”—it sets up a whole system that can kill them. When wood-boring pests pair with a fungus, they can turn healthy stands into stressed stands fast.

The spread mistake is moving untreated wood and materials from place to place. If you’re hauling firewood, logs, or raw wood products, follow guidance and keep it local.

24. Spotted Lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula)

- Hitchhiker pest: Egg masses can travel on vehicles, trailers, and outdoor gear.

- Plant stress: Feeding weakens plants and leaves honeydew that fuels sooty mold.

- Agriculture risk: Can impact grapes, hops, trees, and other high-value plants.

Spotted lanternfly is the invader that spreads like gossip: it rides with people. Egg masses can be on almost anything that sits outside—trailers, firewood racks, lawn furniture, trucks, campers, even rusty equipment you forgot you owned.

The spread mistake is “I didn’t see anything.” That’s exactly how it travels. If Washington residents ever spot it, the smart move is to document and report it quickly—because with pests like this, early action is the whole game.

25. Northern Giant Hornet (Vespa mandarinia)

- Honeybee predator: Can devastate honeybee colonies, threatening pollination.

- Human safety risk: Large hornet with painful stings; encounters can be dangerous.

- Watchlist reality: Even after eradication success, vigilance matters because reintroduction is possible.

Washington learned the hard way what happens when a high-profile invader shows up: everybody pays attention for a while, then attention fades. The problem is, insects don’t need your attention to spread—they just need opportunity.

The spread mistake here isn’t usually intentional movement. It’s missing early signs and assuming “someone else” will catch it. If something looks truly unusual, take a clear photo from a safe distance and report it through the right channels.