You don’t notice invasive species all at once. They don’t crash in loudly. They creep. One vine on a fence. One odd bug on a tree. One plant that suddenly seems to be everywhere.

In North Carolina, these quiet invasions are reshaping forests, clogging lakes, wrecking dunes, and costing homeowners, farmers, and towns real money.

Some of these invaders kill mature trees. Others ruin boat launches, erase wildflowers, or turn backyards into ant minefields. The worst part? Most people help them spread without realizing it.

Below are 25 invasive species causing real damage across North Carolina—what they look like, why they matter here, and the one mistake that helps each one spread.

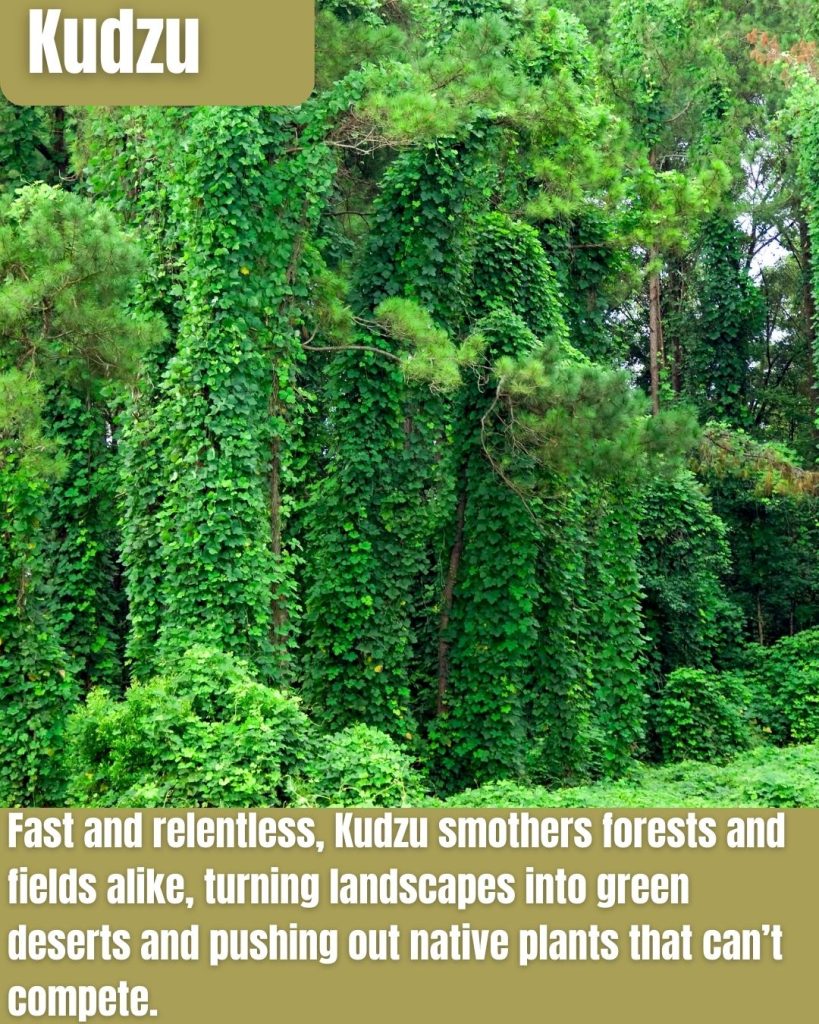

1. Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata)

- Smothers everything: It blankets trees, shrubs, and fences until they can’t photosynthesize.

- Fast takeover: Turns sunny edges and disturbed ground into a single green “blanket.”

- Hard to eliminate: Roots can be deep and stubborn, and regrowth is common without follow-up.

Kudzu is the classic “vine that ate the South,” and North Carolina has plenty of warm, sunny edges where it thrives—roadsides, old fields, powerline cuts, and forest margins.

Cutting alone usually isn’t enough. Successful control is about persistence: repeated cutting, targeted treatment when appropriate, and keeping it from climbing into trees where it becomes a canopy killer.

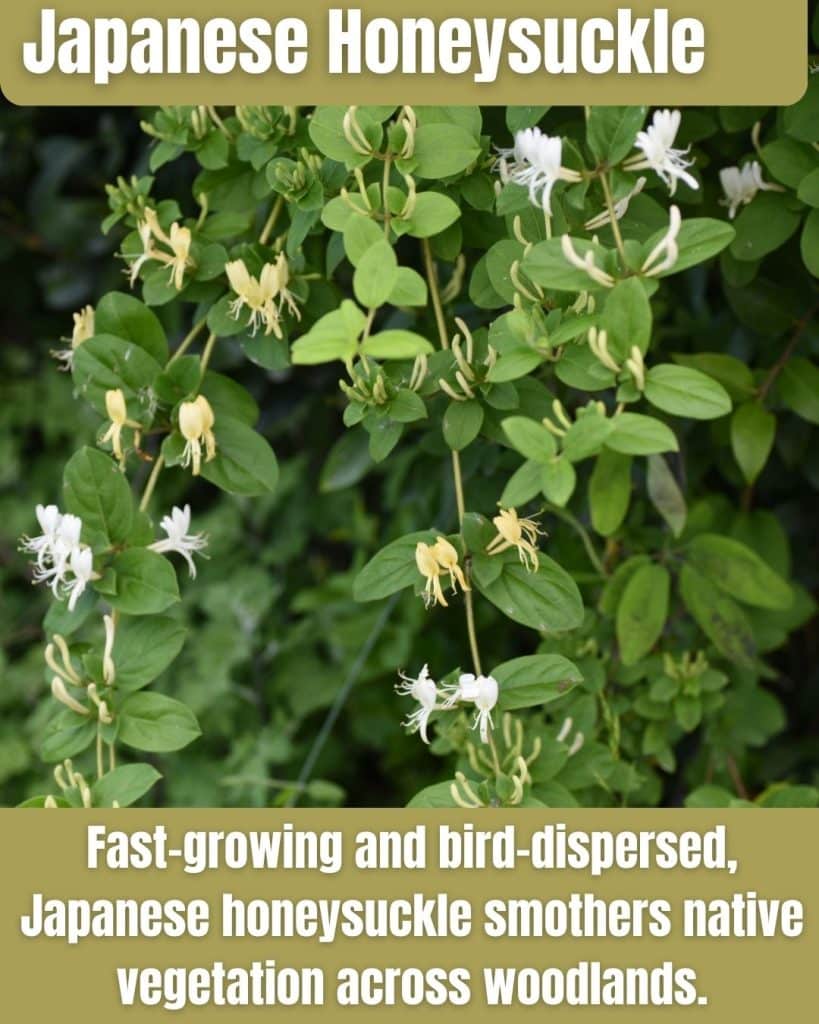

2. Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)

- Mat-maker: Forms thick tangles that crowd out native plants on the forest floor and edges.

- Climbs and strangles: Smothers shrubs and young trees, stealing light.

- Spreads easily: Birds move seeds, and stems can root when they touch soil.

Japanese honeysuckle can look harmless—until you see it weaving through a woodland edge like a net.

In North Carolina, it’s a common takeover plant along trails, fence lines, and sunny forest borders.

The best time to act is before it turns into a blanket. Pulling small patches (roots and all) and preventing it from climbing and seeding keeps it from becoming a long-term headache.

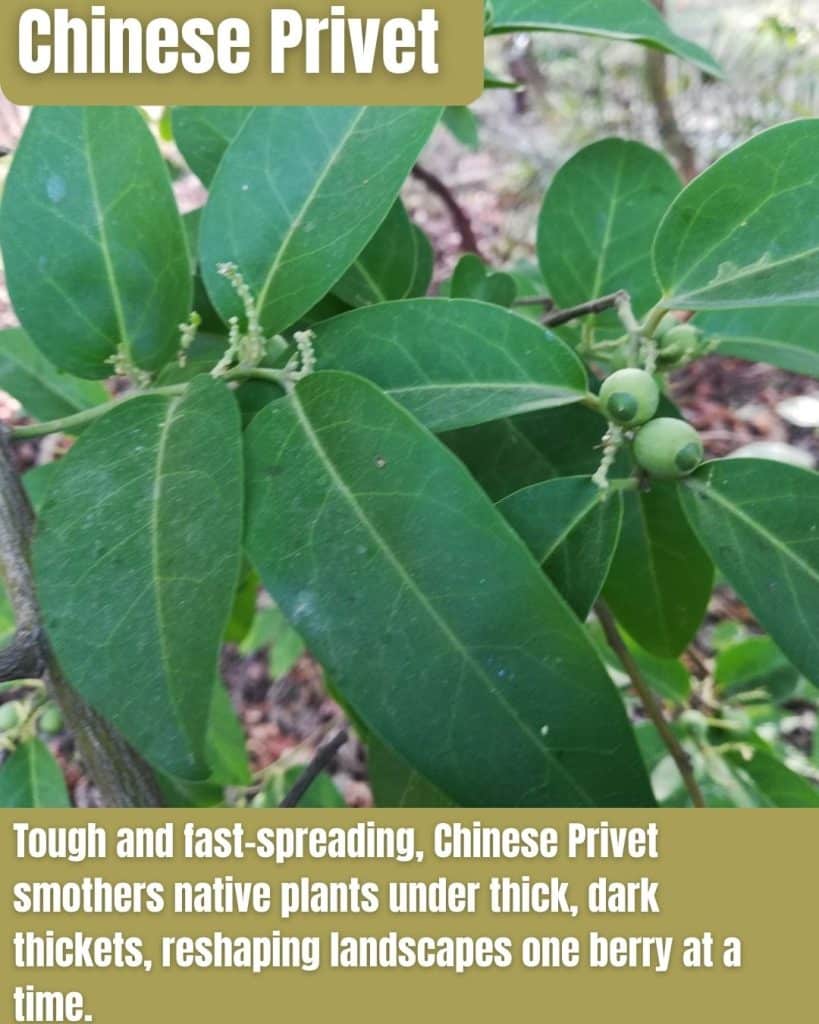

3. Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense)

- Thicket builder: Creates dense walls of shrubs that shade out native seedlings.

- Creek and wetland invader: Often dominates streambanks and bottomlands.

- Bird-spread seeds: Berries help it leap into new areas from landscaping.

Chinese privet is one of those “once it’s in, it’s everywhere” shrubs—especially along North Carolina creeks, floodplains, and shaded woodland edges. It packs in tight, and native plants lose the light battle.

Effective removal usually means cutting and preventing resprouts. If you knock it back once and walk away, it often comes right back thicker.

4. Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

- Chemical warfare: Releases allelopathic chemicals that suppress nearby plants.

- Fast colonizer: Spreads quickly in disturbed areas like roadsides and lots.

- Thicket-former: Sends up sprouts and creates dense stands that crowd out natives.

Tree of heaven thrives in the exact places North Carolina has plenty of: disturbed ground, sunny edges, urban lots, and construction-adjacent areas.

It’s the kind of tree that moves in fast and doesn’t play nice with neighbors.

Cutting can trigger more sprouting, so control usually takes a strategy. If you’re dealing with a patch, the key is stopping it from expanding and seeding into new territory.

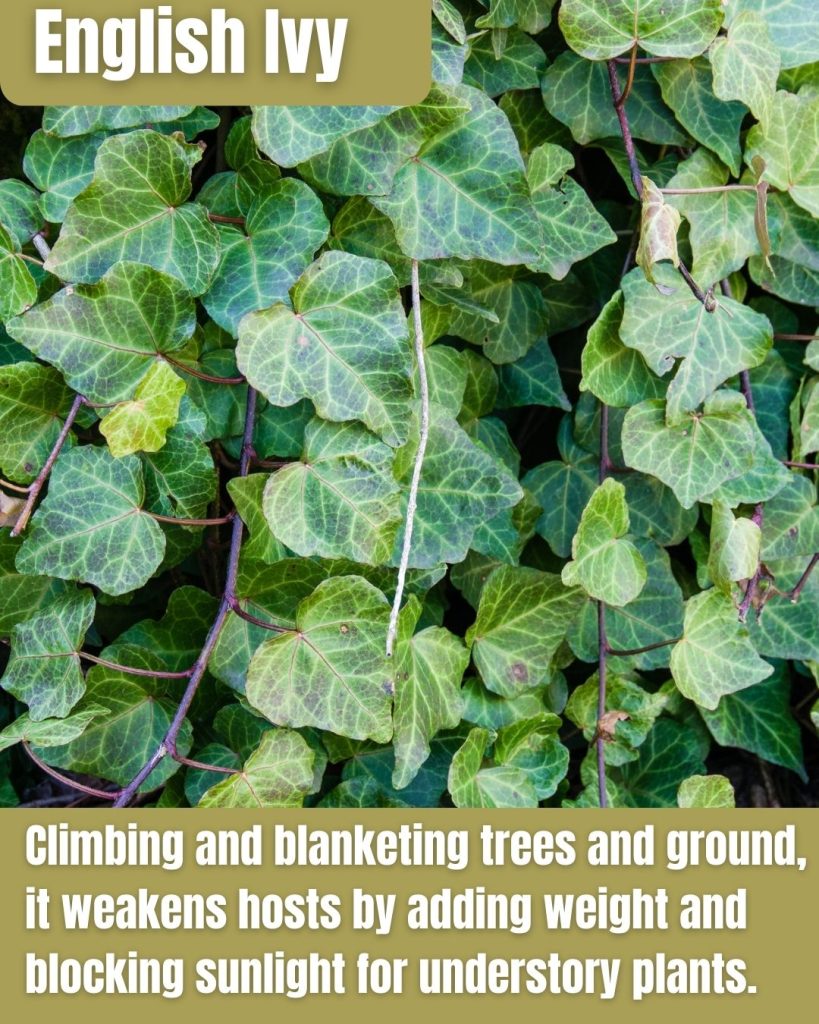

5. English Ivy (Hedera helix)

- Tree-climber: Adds weight and stress to trees, especially in storms.

- Understory smother: Blocks sunlight and crowds out native ground plants.

- Spreads from yards: Landscaping plant that escapes into nearby woods and parks.

In North Carolina neighborhoods and older landscapes, English ivy often starts as “groundcover” and ends up as a woodland problem.

Once it’s climbing, it can change how a stand of trees handles wind and weather.

A practical approach is to cut vines at the base of trees (so the climbing portion dies back) and then work on the ground layer over time. The earlier you start, the easier it is.

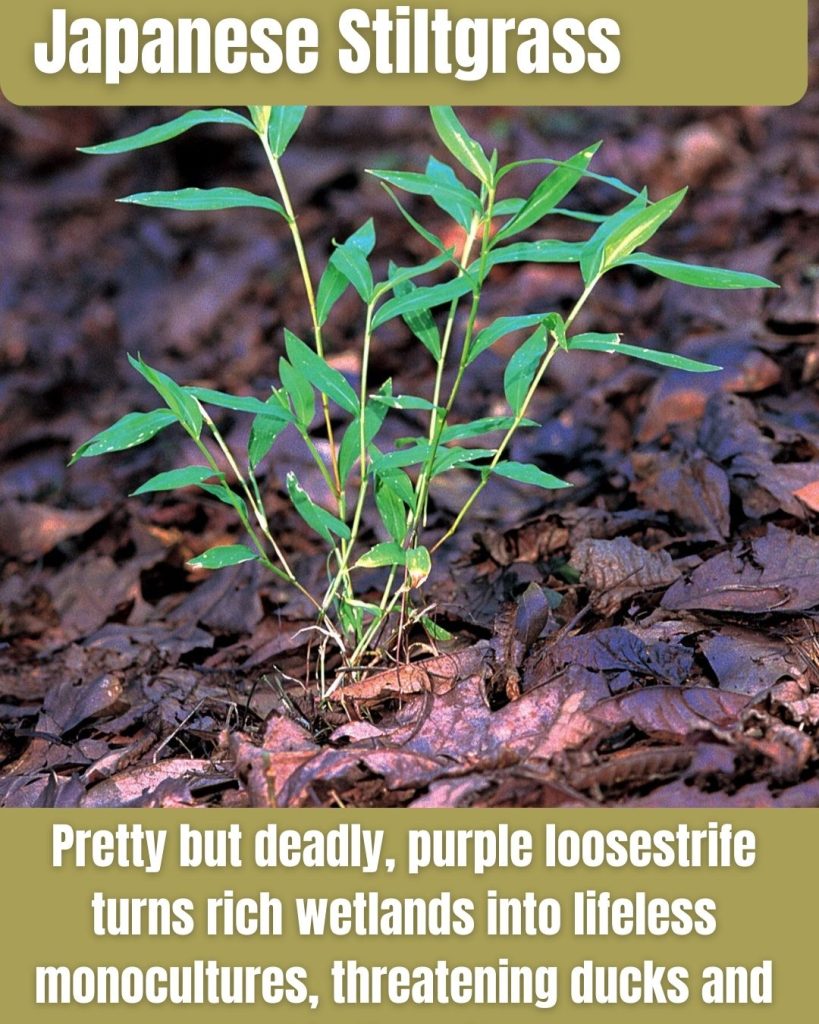

6. Japanese Stilt-grass (Microstegium vimineum)

- Forest-floor carpet: Forms dense mats that block native seedlings.

- Hitchhiker seeds: Spreads on boots, pets, tires, and mower decks.

- Disturbance lover: Trails, creek edges, and thin woods are prime targets.

Japanese stiltgrass is sneaky because it doesn’t always look dramatic at first—then you realize an entire patch of woods is turning into a single-species carpet. North Carolina trail corridors and flood-prone creek bottoms are especially vulnerable.

Timing is everything: cutting or pulling works best before it seeds. Prevention matters too—clean footwear, gear, and mower decks so you don’t “plant” it somewhere new.

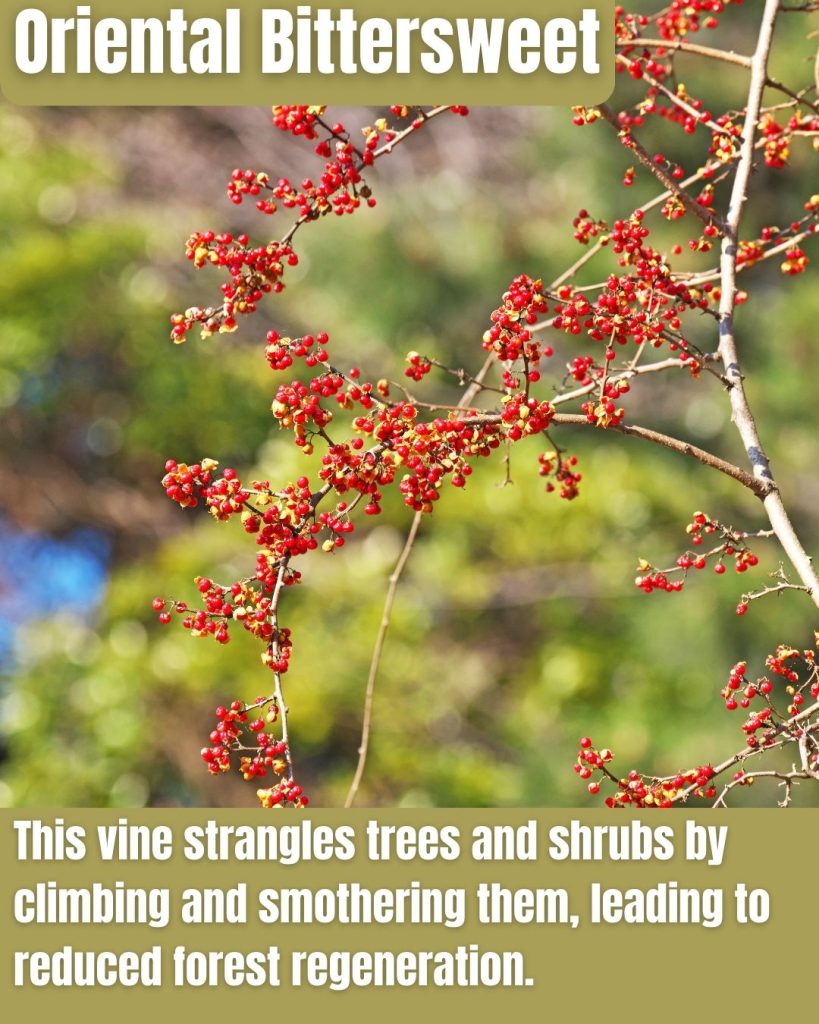

7. Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus)

- Canopy killer: Girdles trunks and drapes over trees until branches break.

- Fast climbing vine: Races into sunlight and overwhelms woodland edges.

- Spreads by berries: Birds carry seeds far beyond where it started.

Oriental bittersweet is one of the worst “vine weight” problems you can get. In North Carolina woods and old fields, it can climb high, wrap tight, and slowly pull the canopy down like a net.

If you see it climbing, don’t wait. Early removal—before it gets into the treetops—can save you a long, expensive battle later.

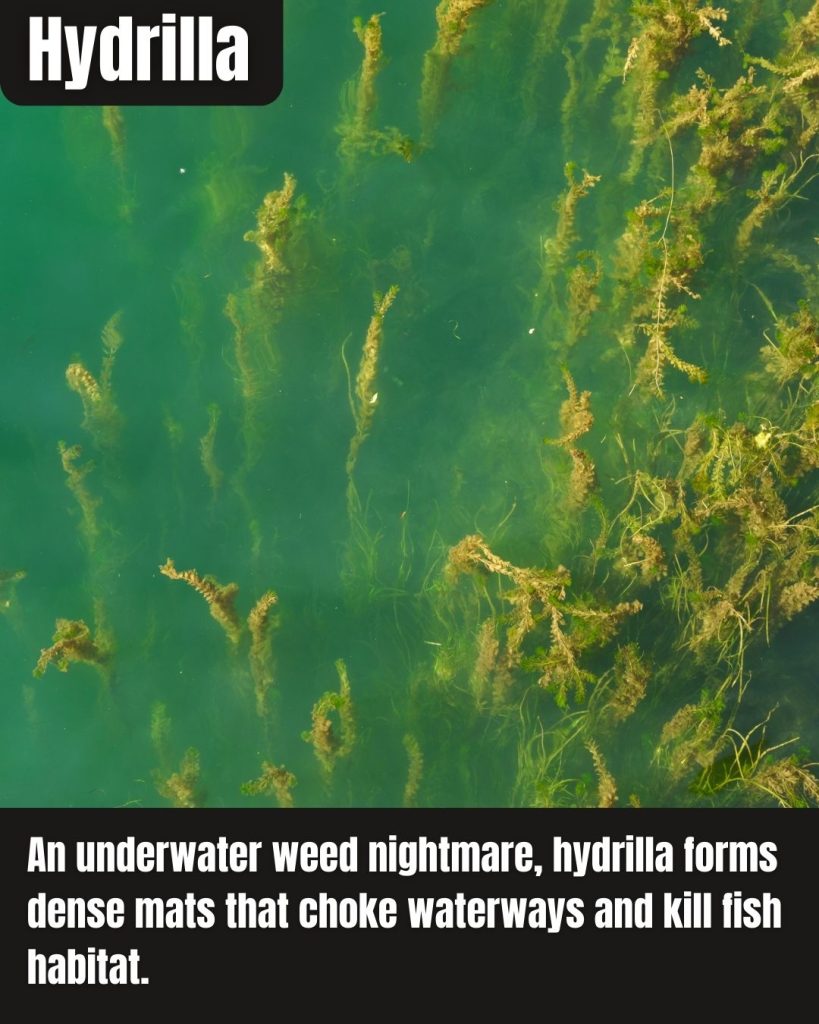

8. Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata)

- Underwater mat maker: Forms thick growth that chokes out native aquatic plants.

- Oxygen trouble: Dense beds can change water conditions and stress fish habitat.

- Spreads by fragments: Tiny pieces hitchhike on props, trailers, and anchors.

Hydrilla can turn good North Carolina fishing and boating water into a clogged mess.

It grows aggressively and can create dense underwater “lawns” that block movement and change the whole shallow-water system.

Boaters are the front line here: remove plants from props and trailers, drain water, and never move aquatic vegetation from one lake or river system to another.

9. Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora)

- Thorny wall: Forms dense, tangled thickets that block access.

- Pasture and edge invader: Takes over field margins, fencerows, and sunny woods.

- Spreads by hips: Birds and wildlife move seeds into new places.

Multiflora rose was once pushed as a “living fence,” but in North Carolina it often becomes exactly that—in the worst way.

It creates thorny barriers that crowd out native shrubs and make land harder to use.

Small plants can be dug if you get the roots. Large thickets usually take repeated control efforts, because it can resprout and expand if it’s only cut back once.

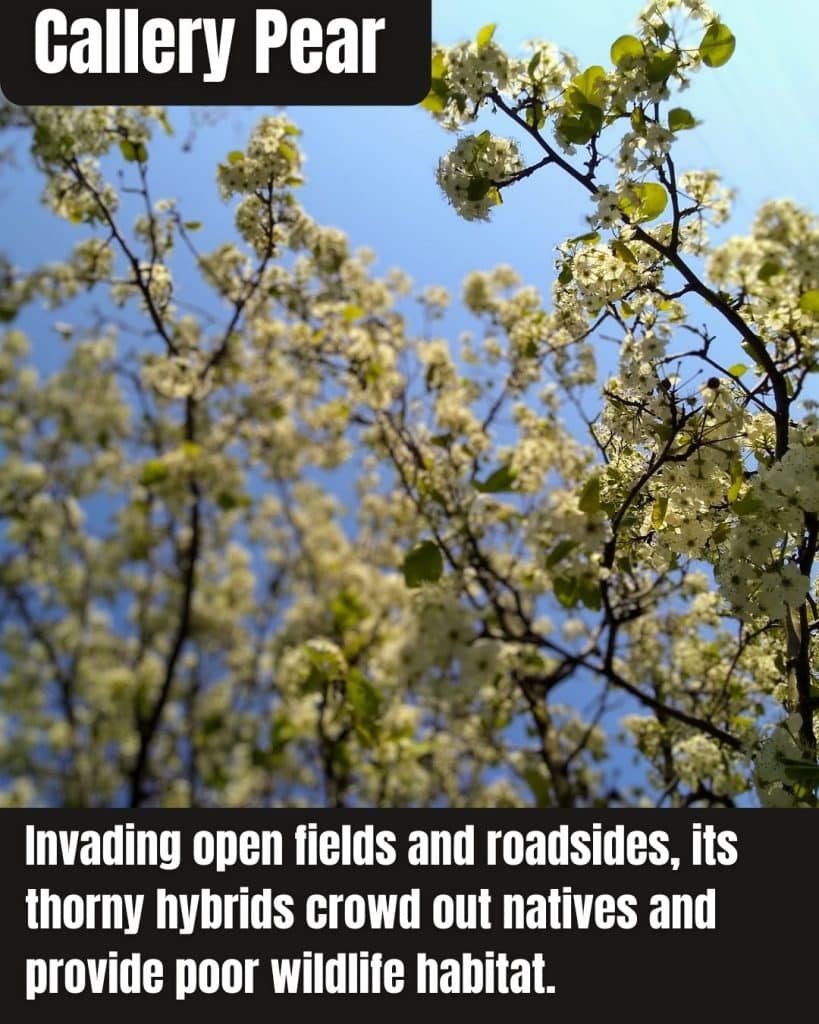

10. Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana)

- Escapes landscaping: Spreads from neighborhoods into fields and woodland edges.

- Monoculture maker: Forms dense stands that outcompete native trees.

- Weak structure: Often breaks in storms, leaving messy, hazardous trees behind.

Callery pear (often known as Bradford pear) is a major escapee in North Carolina.

It spreads into sunny edges and quickly builds thorny thickets that don’t support wildlife the way native trees do.

If you’ve got one in your yard, replacing it with a native option is one of the biggest “do something real” moves you can make. The goal is to stop the seed source feeding nearby invasions.

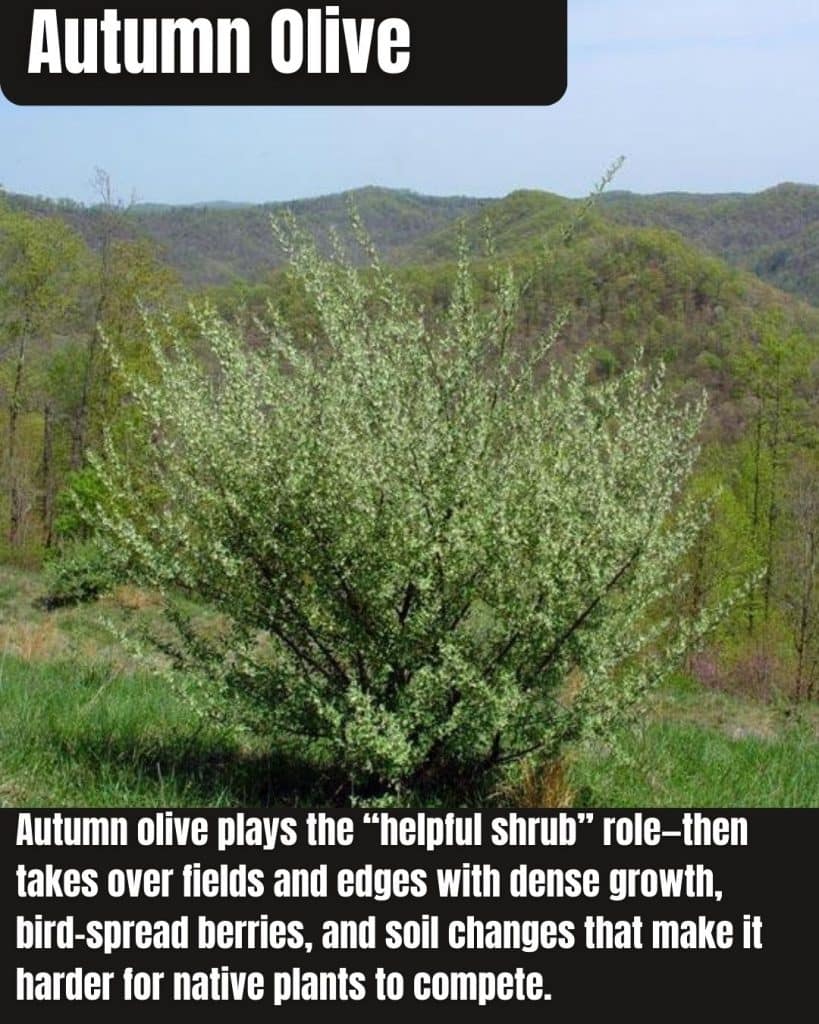

11. Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata)

- Field takeover: Quickly dominates old fields and sunny woodland edges.

- Soil changer: Fixes nitrogen and alters conditions in ways that favor invasives.

- Bird-spread berries: Seeds travel far from where it was planted.

Autumn olive was planted for “wildlife” and erosion control, but it often turns into a thicket problem in North Carolina—especially along roadsides, rights-of-way, and abandoned fields.

Cutting alone usually leads to resprouting. Long-term control is about repeated follow-up and preventing it from producing berries that fuel new infestations.

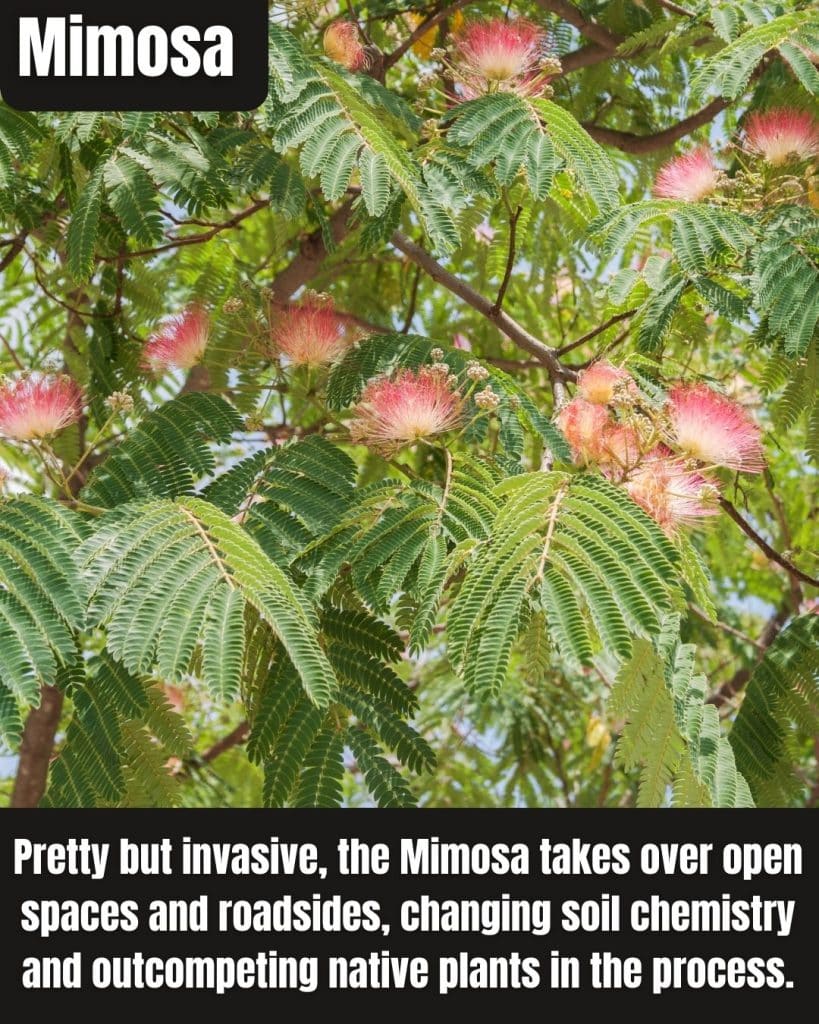

12. Mimosa (Albizia julibrissin)

- Quick shade: Crowds out young native trees and understory plants.

- Seeds spread easily: Pops up along roads, streams, and disturbed soil.

- Low habitat value: Doesn’t replace what native trees provide for wildlife.

Mimosa is pretty—and that’s part of the problem. In North Carolina, it escapes landscaping and shows up along roadsides, creek corridors, and disturbed ground, where it can shade out native regeneration.

Keeping it from seeding is key. If you remove it, stay on top of seedlings for a while, because they love popping up after soil disturbance.

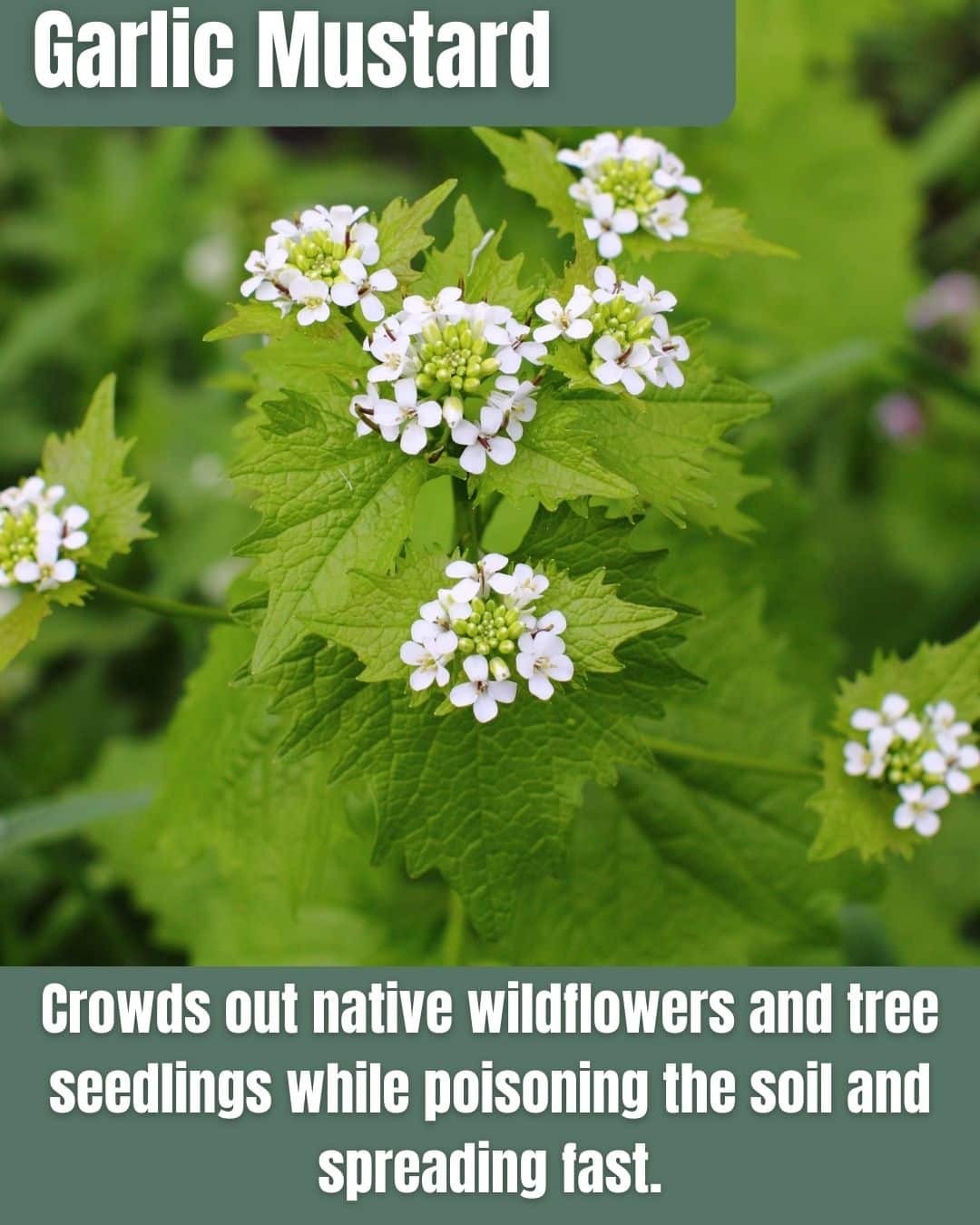

13. Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

- Spring carpet: Crowds out native wildflowers in woodlands.

- Soil disruption: Interferes with fungi many native plants rely on.

- Seed staying power: Seeds can persist, so follow-up matters.

Garlic mustard is a serious woodland invader in many parts of North Carolina, especially in rich, moist woods and along trails. It shows up early, shades out spring wildflowers, and can quietly shift what a forest floor looks like over time.

Hand-pulling works best before flowers turn into seed pods. Bag it if it’s flowering, because pulled plants can still ripen seed if left on the ground.

14. Chinese Wisteria (Wisteria sinensis)

- Tree strangler: Wraps tightly and can girdle trunks and branches.

- Smothering canopy: Climbs high and blocks light from native plants below.

- Structural damage: Heavy vines can damage fences, sheds, and even trees in storms.

Wisteria looks like a postcard when it blooms, but in North Carolina woods it can act like a wrecking ball. Once it gets into trees, it adds weight, blocks light, and can eventually pull down branches and canopies.

If you see wisteria escaping a yard or climbing into woodland edges, that’s the time to act. The longer it grows, the more muscle it takes to remove.

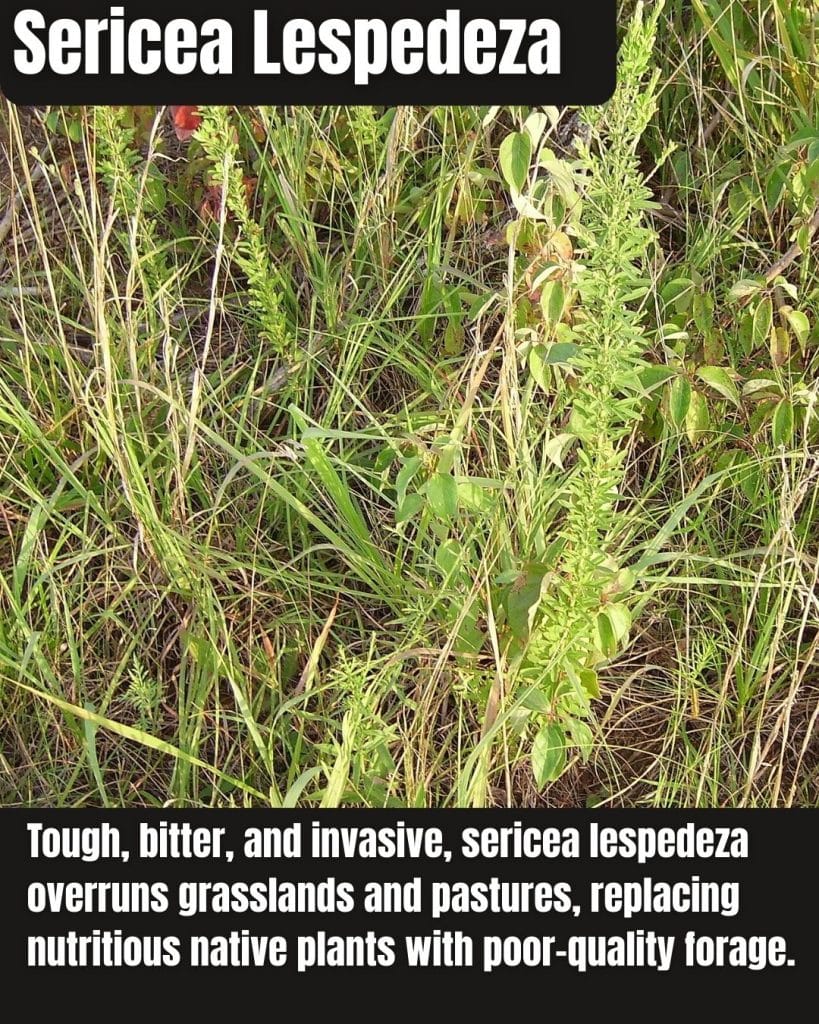

15. Sericea Lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata)

- Grassland takeover: Forms dense stands that crowd out native grasses and flowers.

- Low forage value: Reduces quality habitat for native herbivores and grazing lands.

- Seed producer: Once established, it can keep reseeding and spreading.

Sericea lespedeza is a major problem plant in open habitats—roadsides, pastures, old fields, and sunny slopes.

In North Carolina, it can push out the diverse mix of plants that pollinators and wildlife depend on.

Preventing seed production is huge. If it’s allowed to mature and reseed year after year, it gets harder to reclaim the ground for natives.

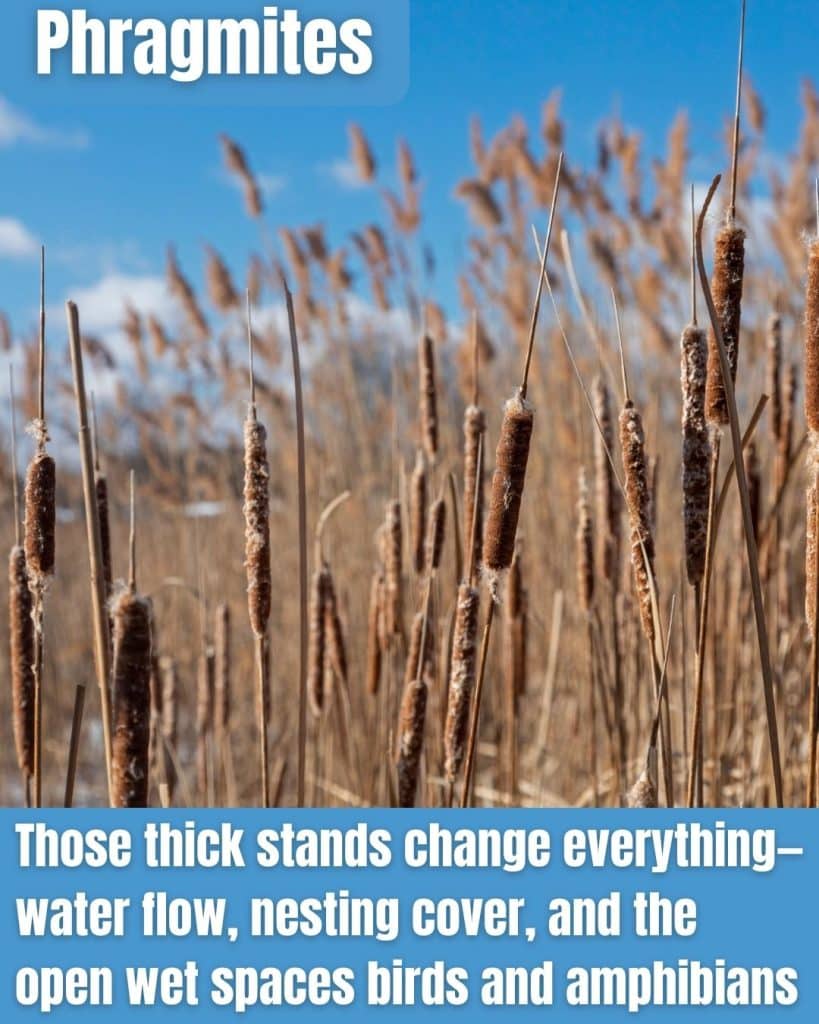

16. Phragmites (Phragmites australis)

- Wetland wall-builder: Forms tall, dense stands that crowd out native plants.

- Habitat downgrade: Replaces diverse marsh plants with a monoculture.

- Hard to remove: Spreads by seed and rhizomes, and rebounds after cutting.

Phragmites is one of the most “seen everywhere” invasives in North Carolina—especially along roadsides, ditches, shorelines, and coastal wetlands. It grows like a living fence and slowly squeezes out the diversity that makes marshes work.

Control usually takes a plan (often herbicide + follow-up), because cutting alone can make it come back thicker.

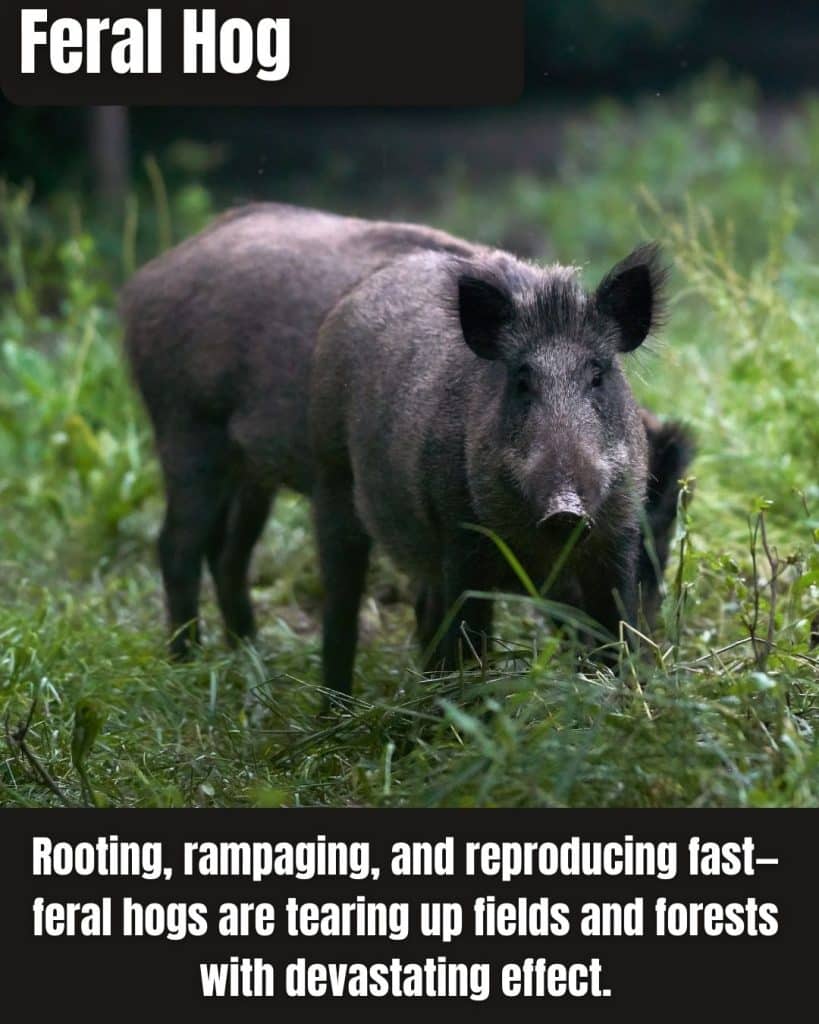

17. Feral Swine

- Soil destroyers: Root up ground like rototillers, damaging forests, fields, and wetlands.

- Crop damage: Tear up farms, food plots, and gardens.

- Disease risk: Can spread diseases that impact livestock, wildlife, and pets.

Feral swine are not a “nuisance animal.” They’re a habitat and agriculture wrecking crew. In parts of North Carolina, they can tear up huge areas overnight, leaving erosion and damaged vegetation behind.

If you’re seeing rooting damage, wallows, or repeated sign, reporting it matters. These populations grow fast, and early response is far easier than trying to fight an established herd.

18. Emerald Ash Borer

- Fast ash killer: Infestations can kill trees in just a few years.

- Canopy loss: Neighborhoods and forests lose shade and stability.

- Firewood spread: Moving firewood is one of the easiest ways to help it travel.

North Carolina has ash trees in natural areas and in towns, and emerald ash borer can wipe them out fast. Larvae tunnel under the bark and cut off the tissues that move water and nutrients—so a healthy-looking tree can decline quickly once infestation takes hold.

If there’s one “do this every time” rule, it’s don’t move firewood. Buy it where you burn it—especially when camping or traveling across the state.

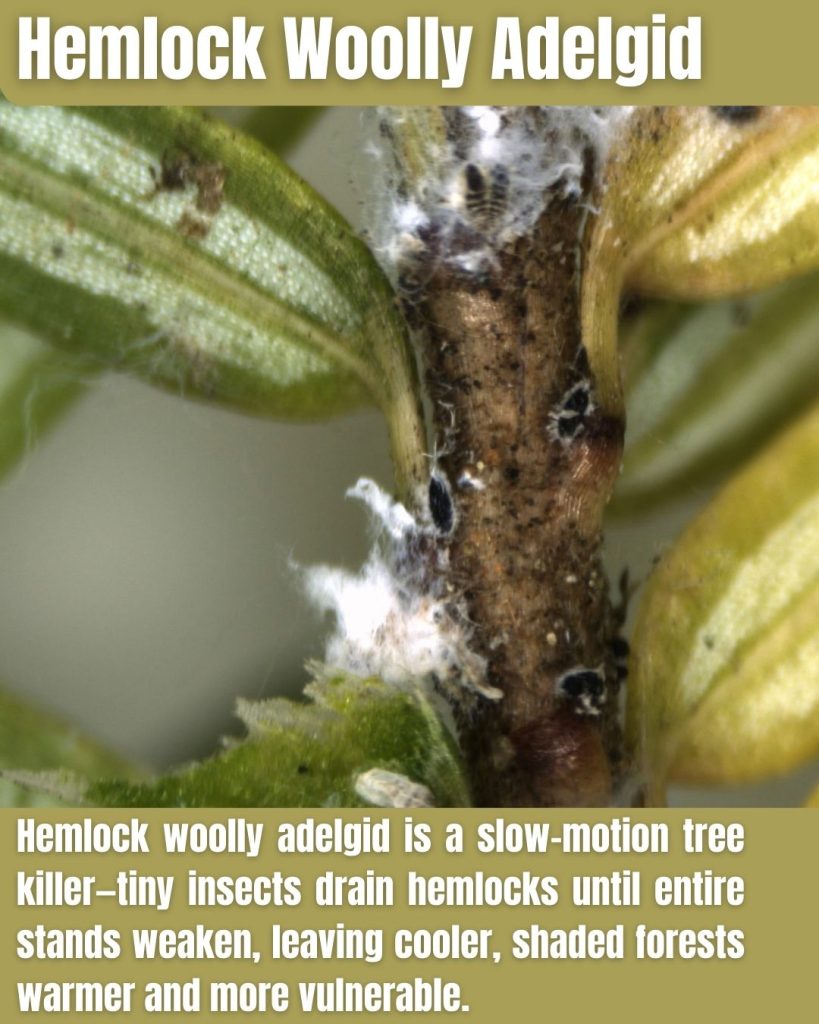

19. Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

- Hemlock killer: Weakens trees by feeding on sap, leading to decline.

- “Cottony” clue: White woolly masses on twigs are a common sign.

- Stream impacts: Losing hemlock shade can warm streams and change habitat.

In North Carolina’s mountain forests, hemlocks help create that cool, shaded feel along creeks and coves. Hemlock woolly adelgid threatens that by draining trees until they can’t keep up, and whole stands can decline over time.

Early detection matters. If you notice the cottony clusters on hemlock twigs, it’s worth reporting so professionals can confirm and respond in the right way.

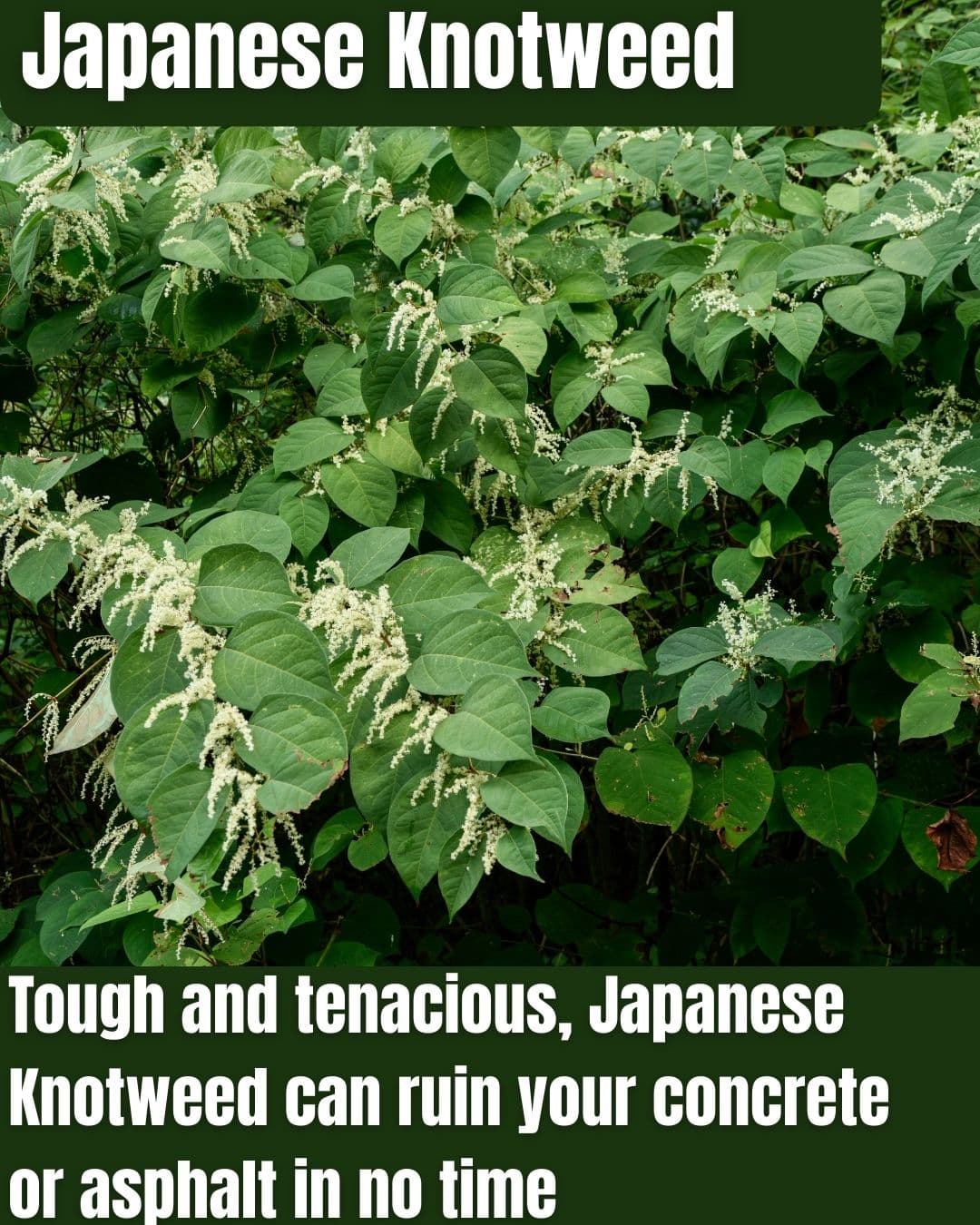

20. Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

- Streambank takeover: Forms dense stands that crowd out native plants.

- Erosion risk: Can leave banks vulnerable when growth dies back seasonally.

- Fragment regrowth: Small pieces of root or stem can start new infestations.

Japanese knotweed loves disturbance, and North Carolina has plenty of it—streambanks, ditches, road edges, construction sites, and flood-prone areas. Once it gets a foothold, it builds thick stands that block light and push everything else out.

For most homeowners, the reality is this: it usually takes a multi-year plan, and careless cutting can spread it if fragments get moved downstream or hauled off with yard waste.

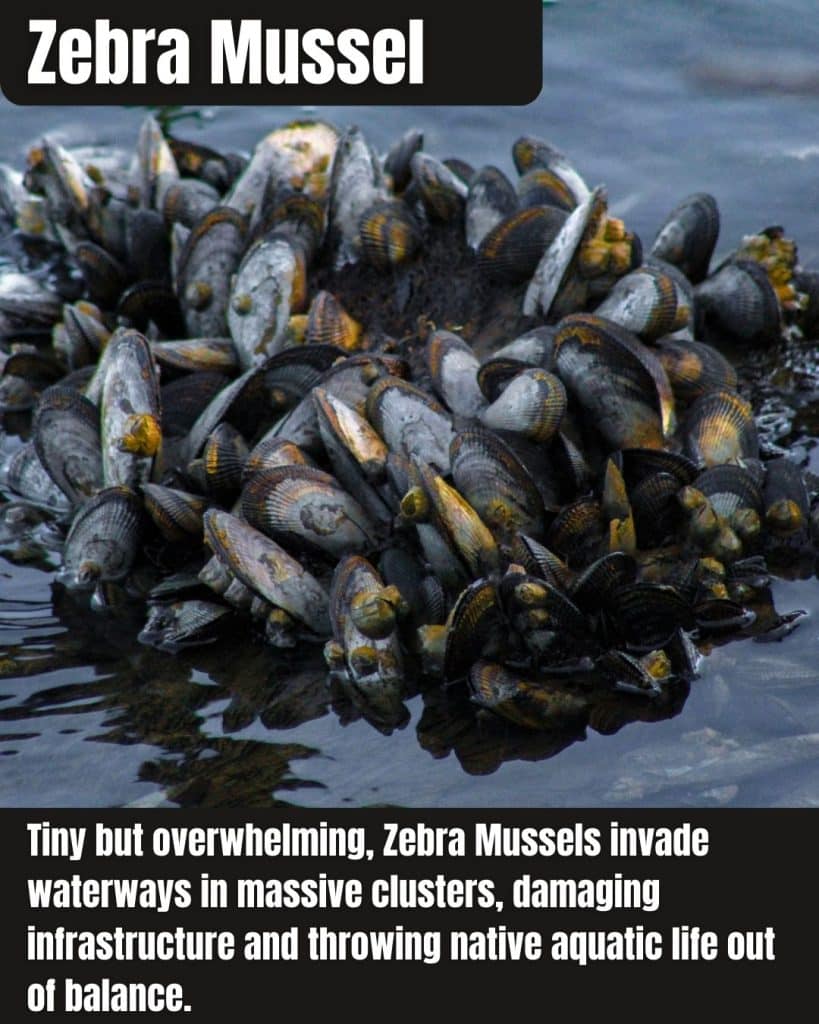

21. Zebra Mussel

- Clogs infrastructure: Pipes, intake screens, and marina equipment can get packed with shells.

- Smothers native mussels: They attach in piles, stressing or killing native species.

- Sharp hazard: Shorelines can turn into “shell beds” that cut feet and paws.

Zebra mussels are small, but they act like a living, multiplying coating. Once they get established, they attach to almost anything hard—docks, rocks, boat hulls, and water intakes—and they don’t stop.

The best defense is prevention: Clean, Drain, Dry boats and gear, and never move water or bait between lakes and rivers.

22. Fire Ant

- Painful stings: Aggressive ants that can swarm and sting repeatedly.

- Yard and field disruption: Mounds interfere with mowing, grazing, and outdoor activities.

- Equipment damage: Can damage electrical equipment and outdoor systems.

Fire ants are more than an annoyance—anyone who’s stepped into a mound knows how fast a small mistake turns into a painful situation. In parts of North Carolina, they can create real issues for yards, farms, and outdoor recreation.

If you’re seeing repeated mounds, don’t ignore them. Early control is far easier than letting a population build and spread across a property.

23. Spotted Lanternfly

- Hitchhiker pest: Egg masses can travel on vehicles, trailers, and outdoor gear.

- Plant stress: Feeding weakens plants and leaves honeydew that fuels sooty mold.

- Agriculture risk: Can impact grapes, trees, and other high-value plants.

The spotted lanternfly spreads because it’s good at riding with people. Egg masses can end up on almost anything—especially items that sit outside, then travel across counties or across state lines.

If North Carolina residents spot it, the smart play is to document it and report it through recommended state/local channels. With invasives like this, early action is the whole game.

24. Japanese Beetle

- Leaf skeletonizer: Adults chew leaves into lace, stressing ornamentals and crops.

- Wide menu: Feeds on many plants, so it spreads damage across landscapes.

- Turf connection: Larvae (grubs) can damage lawns and attract digging animals.

Japanese beetles are a summer gut-punch in North Carolina landscapes. One day the plants look fine, and a week later you’ve got leaves that look “burned” and chewed down to veins.

Managing them is usually about reducing pressure over time—protecting high-value plants, watching for peak activity, and keeping grub damage in turf from turning into the next wave.

25. Beach Vitex (Vitex rotundifolia)

- Dune takeover: Crowds out native dune plants that stabilize sand.

- Erosion risk: Alters how dunes function, which can increase vulnerability.

- Wildlife habitat loss: Reduces quality habitat for beach-nesting wildlife.

Beach vitex is a coastal invader that hits North Carolina where it hurts: the dunes. Those dunes are more than scenery—they’re natural protection for beaches and nearby communities, and they’re critical habitat for coastal wildlife.

If you see it spreading on dunes, treat it seriously. Coastal invasives can move fast, and removal is much easier before it becomes a large, established patch.