Texas is under siege. From starlings in the sky to hogs in the fields and fish in the lakes, invasive species are disrupting ecosystems across the state.

These unwelcome guests are tough, fast-breeding, and costly. Here’s a look at the worst offenders threatening Texas’s land, water, and wildlife.

Birds

Texas is home to several invasive bird species that disrupt local ecosystems. These birds often compete with native birds for food and nesting sites, sometimes even displacing them.

Introduced primarily from other continents, they can also cause agricultural damage and urban nuisances.

Invasive species such as starlings and house sparrows pose major threats to native bird populations.

European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

- Introduced on purpose: Brought to the U.S. by Shakespeare fans trying to introduce every bird mentioned in his works.

- Feathered squatters: Outcompete native birds like bluebirds and woodpeckers by hijacking nesting holes.

- Crop and health menace: Massive flocks destroy crops, spoil cattle feed, and spread diseases through toxic droppings.

Brought from Europe in the 1890s, starlings now number over 200 million in North America. They aggressively compete with native cavity-nesting birds (like bluebirds and woodpeckers) by taking over nest holes .

Starlings also flock in huge numbers that destroy crops (grains, fruit) and contaminate livestock feed, and their droppings can carry diseases such as histoplasmosis.

Notably, their spread across Texas has made them a persistent agricultural pest and urban nuisance.

House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)

- Feathered freeloaders: Originally from Europe and the Middle East, they now dominate Texas cities and farms.

- Tiny but vicious: Known to attack and evict native birds from nest boxes, even mid-nesting.

- Breeding machines: Can raise several broods a year, giving them a numbers advantage in the battle for habitat.

Introduced from the Middle East and Europe in the 19th century, this little brown sparrow is now one of the most widespread birds in Texas.

House sparrows thrive in urban areas and near people. They are notorious for aggressive behavior toward native birds. They will invade nest boxes and evict or even attack native songbirds to take over nesting sites.

They can raise multiple broods per year and feed on grains and insects, sometimes stealing food from other birds.

House sparrows now pose a serious threat to native bird species by out-breeding and out-competing them for habitat.

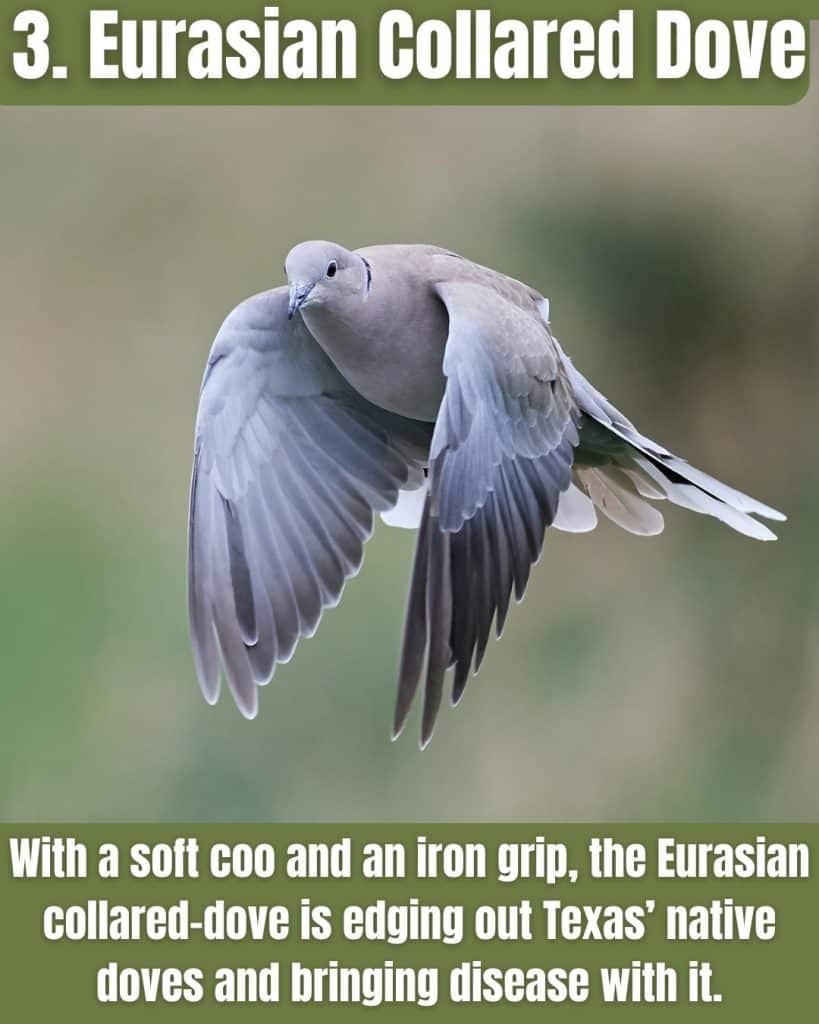

Eurasian Collared Dove (Streptopelia decaocto)

- Fast-track invasion: From the Bahamas in the ’70s to Texas suburbs by the ’90s — they spread like wildfire.

- Feeder bullies: Dominate backyard feeders and outcompete native doves like the gentle mourning dove.

- Disease threat: Can transmit parasites to native doves and the raptors that eat them.

A pale gray dove with a black neck collar, originally from Asia, now rapidly expanding across Texas.

First introduced to the Bahamas in the 1970s, collared doves spread to Florida and then Texas by the 1990s.

Extremely prolific breeders, they can raise several broods a year and are successful colonizers. In Texas, they frequent suburbs and farms, often dominating bird feeders. Scientists suspect (suspect?) they compete with native doves (like mourning doves) for food and nesting space.

They also carry parasites (e.g., Trichomonas) that can spread disease to native doves and even the hawks that prey on them.

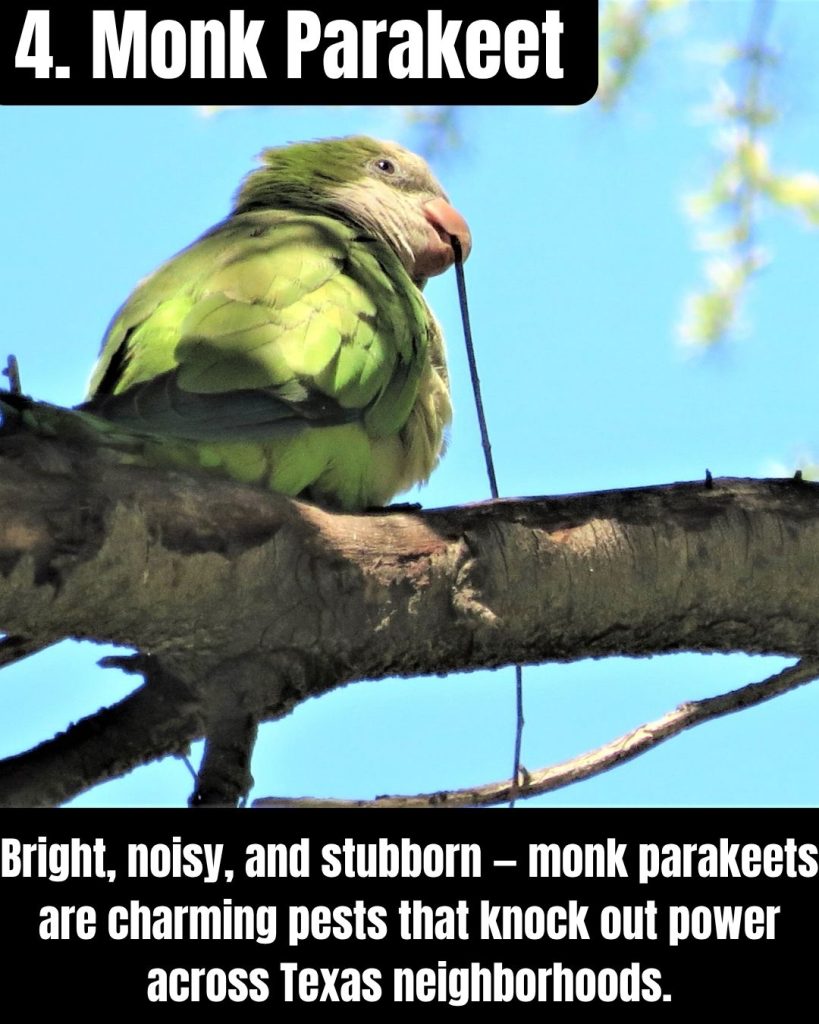

Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus)

- Power-hungry pests: Their massive stick nests on transformers and poles can spark blackouts.

- Tough little parrots: Unlike tropical cousins, they survive Texas winters by huddling in communal nests.

- Serial rebuilders: Remove a nest, and they’ll rebuild it the same day — often in the same spot.

Also known as the Quaker parrot, this bright-green parakeet from South America has formed feral colonies in Texas cities (e.g. Houston, Austin).

Notorious for their large communal nests, monk parakeets build massive stick nests on utility poles and transformers, causing power outages.

Unlike many parrots, they tolerate cold weather by nesting in groups. While initial fears of crop damage proved unfounded, they cause significant damage to electrical infrastructure.

Even if nests are removed, the parrots often rebuild at the same site within hours.

Introduced via the pet trade in the 1960s, they now thrive in Texas due to their adaptability and lack of natural predators.

Rock Pigeon (Columba livia)

- Urban squatters: Descended from homing pigeons, they thrive on rooftops, statues, and city ledges.

- Toxic mess-makers: Their droppings are corrosive and can damage buildings, bridges, and monuments.

- Health hazard: Guano buildup can harbor dangerous fungi that threaten human health.

The common “city pigeon” is an Old World species long established in Texas towns and cities. Descended from domestic homing pigeons, feral pigeons gather in flocks on buildings and public areas.

They are considered invasive because of their high numbers and the problems they cause in urban centers.

Pigeon droppings are not only unsightly but acidic and corrosive, which accelerates the deterioration of metal and stone structures.

Large accumulations of guano can also harbor fungi and pathogens. Pigeons have been associated with diseases such as histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis, which pose health risks to humans.

Insects

Invasive insects in Texas cause extensive ecological and economic damage. These pests often have no natural predators here, allowing their populations to explode.

They may defoliate forests, destroy agricultural crops, or spread plant diseases. Many arrived via global trade, hitchhiking in cargo or plants.

As a result, Texas is battling everything from aggressive fire ants to tree-killing beetles. Controlling these insects is critical, since they spread rapidly and out-compete native insects for resources, sometimes fundamentally altering habitats.

Red Imported Fire Ant (Solenopsis invicta)

Perhaps Texas’s most infamous insect invader, this venomous ant came from South America (likely via ship cargo in the 1930s). Fire ants spread rapidly across the South, forming huge colonies.

Their impacts are widespread: they aggressively attack ground-nesting animals, sting humans (painfully and repeatedly), and even damage electrical wiring and equipment.

They can also reduce crop yields by feeding on germinating seeds and harassing livestock. Fire ants have become a major pest in Texas, and their large mounds can disrupt farming and fun.

They are tough to get rid of, given the ants’ ability to rebound quickly.

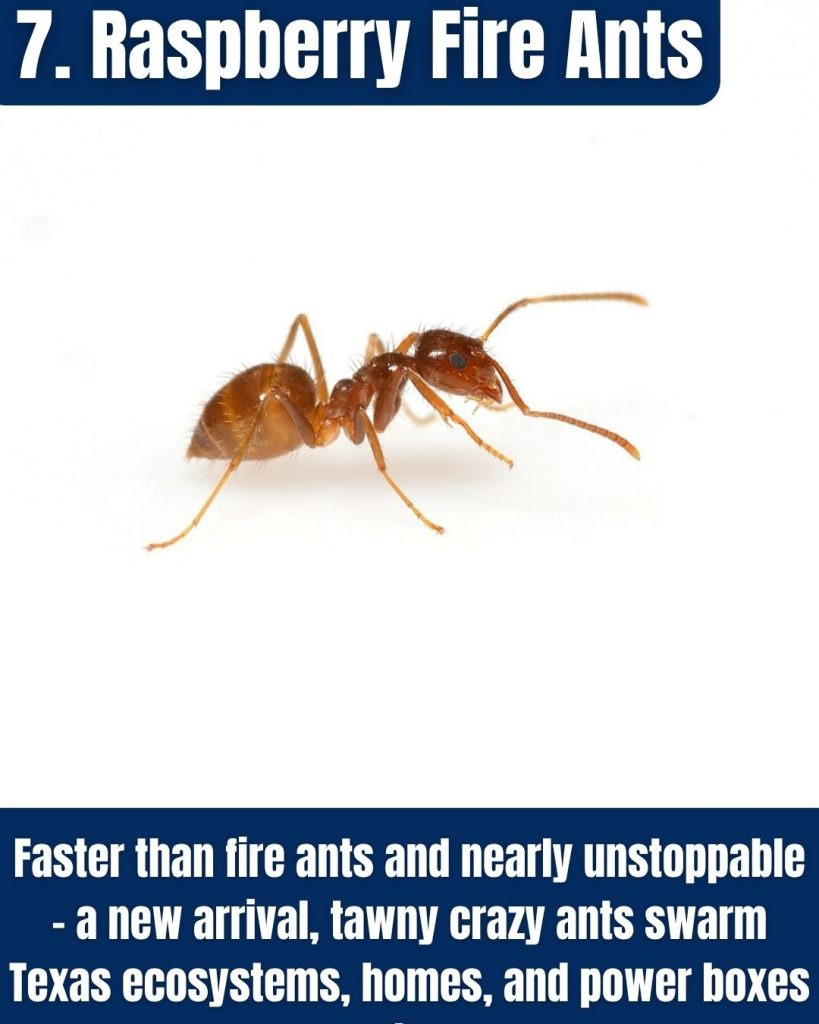

Tawny (Rasberry) Crazy Ant (Nylanderia fulva)

- They beat fire ants: These invaders evolved resistance to fire ant venom and are pushing them out in some regions.

- Insatiable swarms: They don’t sting, but they pour into homes, cars, and electronics, shorting out gear and swamping structures.

- Ecosystem wreckers: Devour native insects, spiders, and even small animals, leaving little behind for birds or other wildlife.

A newer invader (first found in Texas in 2002) that is in some areas even worse than fire ants. Originating from South America, tawny crazy ants form enormous super-colonies with multiple queens.

They have even displaced fire ants in parts of Texas by evolving a resistance to fire ant venom.

Crazy ants don’t sting, but they overwhelm environments by sheer numbers… infesting homes, swarming into electrical boxes and vehicles, and wiping out native insects.

They’ll nest in any cavity, often invading buildings and causing electrical shorts.

Outdoors, they consume nearly every insect (and even small vertebrates) they encounter, which means native insects, spiders, and even nesting songbirds can be overrun by these ants.

Their explosive spread and difficult control make them a serious emerging threat in Texas.

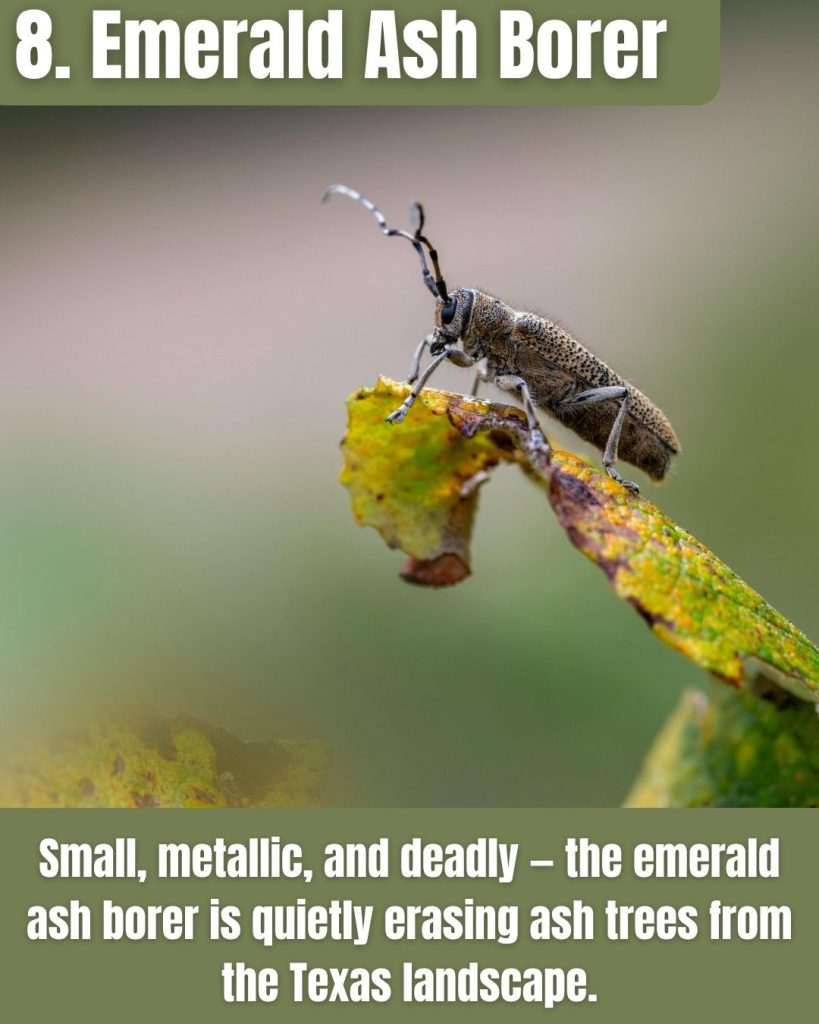

Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis)

- Tree assassin: Its larvae burrow under bark, choking ash trees to death in just 2-3 years.

- Late to Texas, but fast-moving: Detected in 2016, it’s already confirmed in dozens of counties, especially in the northeast.

- Ashpocalypse now: Threatens to wipe out native ash trees that provide shade, habitat, and valuable hardwood.

A shiny green wood-boring beetle from Asia that is devastating Texas ash trees.

EAB was first detected in Texas in 2016 after killing millions of ash trees across the eastern U.S. This insect’s larvae tunnel under the bark of ash trees, girdling and killing them within 2-3 years.

All native ash species (including Texas’s green and white ash) are at risk.

Since its arrival, the EAB has been confirmed in dozens of Texas counties, especially in the northeast. The beetle’s spread threatens urban shade trees and forest ecosystems, ash trees are important for wildlife and used for lumber.

Texas forest officials warn that without intervention, EAB could eliminate ash from Texas forests, with major economic and ecological consequences .

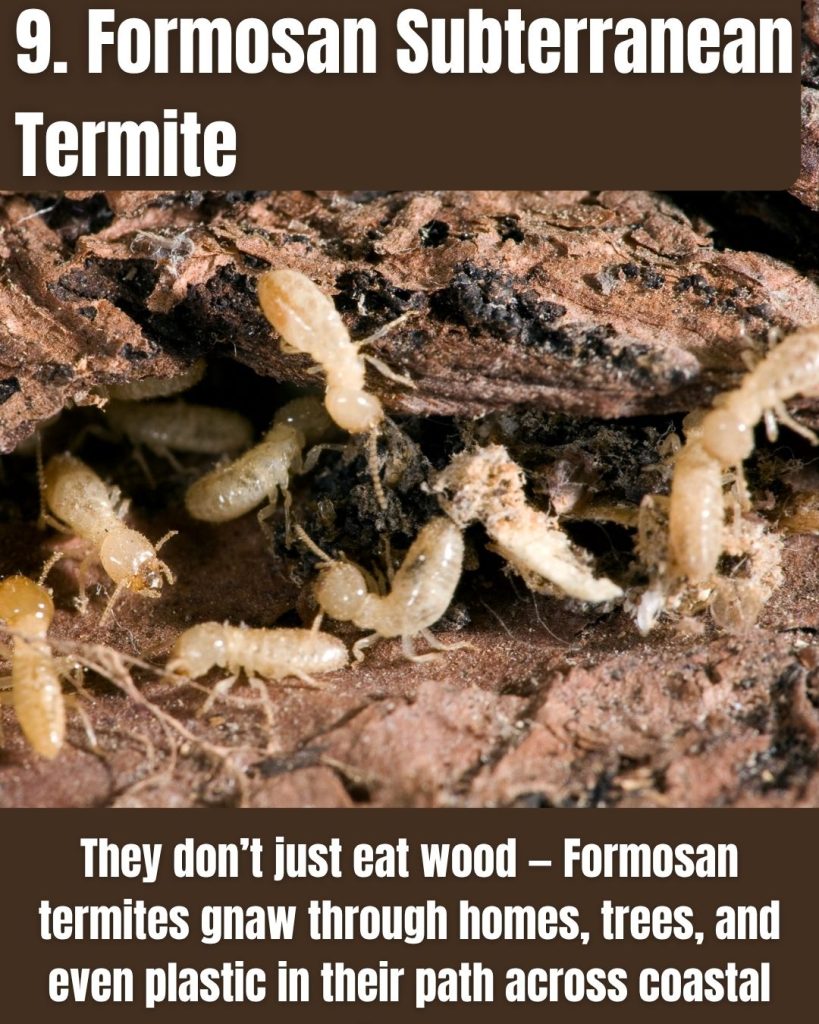

Formosan Subterranean Termite (Coptotermes formosanus)

- Not your average termite: Known as “super-termites,” their colonies can be millions strong and chew through more than just wood.

- Material munchers: Can tunnel through plastic, asphalt, and even soft metal to reach their next meal.

- Silent homewreckers: Can cause severe structural damage to buildings in under two years — even from aerial nests.

An extremely destructive termite species native to China, now established in parts of Texas (especially Gulf Coast cities).

Formosan termites are nicknamed the “super-termite” for their huge colonies and voracious appetite. They attack over 50 species of living plants and any wood in structures.

Remarkably, they can even chew through non-wood materials like plastic, asphalt, or soft metals to get at a food source.

A single Formosan colony can number in the millions of termites, able to cause severe structural damage to an unprotected house in as little as two years.

Unlike native termites, they can form aerial colonies (without ground contact), making them harder to control.

Texas homeowners now face costly repairs as this invasive termite spreads, causing millions of dollars in damage each year.

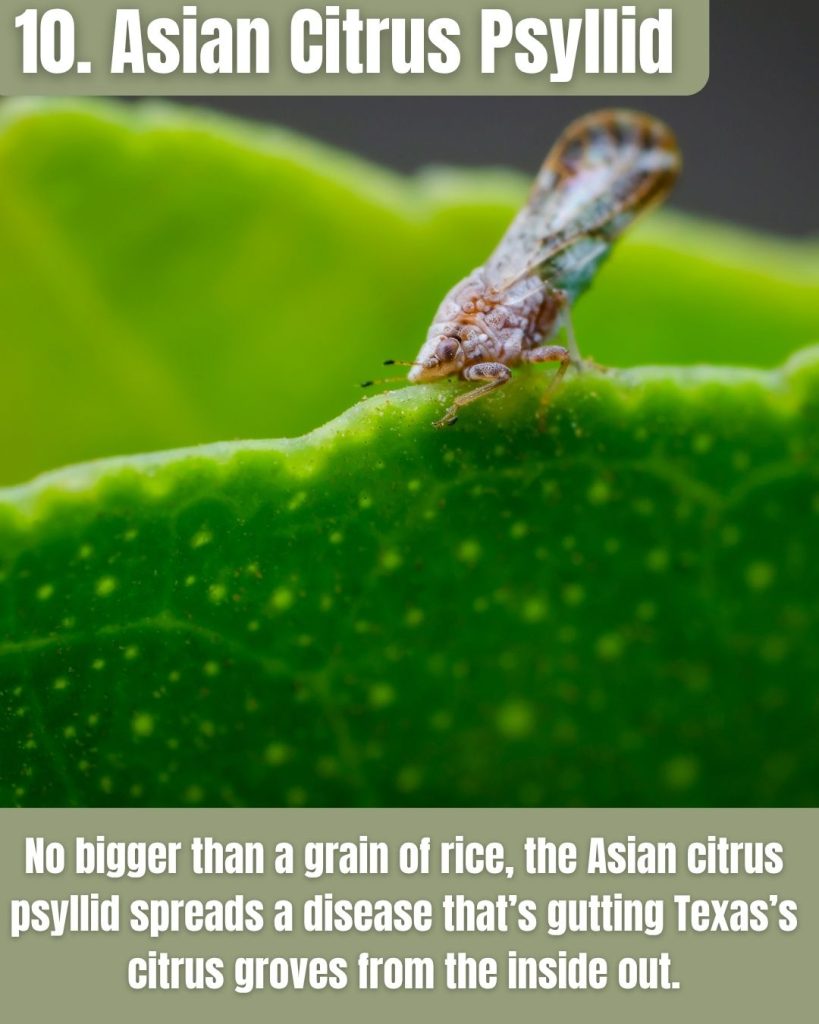

Asian Citrus Psyllid (Diaphorina citri)

- Tiny but deadly: Spreads citrus greening disease (HLB), one of the most destructive plant diseases on earth.

- Industry killer: Has already crippled Florida’s citrus industry — now threatening groves in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley.

- Under quarantine: Its fast spread forced the USDA to quarantine the entire state of Texas.

A tiny sap-sucking insect with an outsized impact, the Asian citrus psyllid is the primary vector of citrus greening disease (huanglongbing).

The psyllid itself feeds on citrus leaves, but the real danger is the bacteria it spreads, which cause citrus greening… a lethal disease of citrus trees.

Citrus greening has devastated Florida’s groves and was detected in South Texas in the 2010s.

Because the psyllid can move the disease quickly, the USDA quarantined all of Texas for this pest. Infested trees become stunted, produce bitter, misshapen fruit, and eventually die, threatening Texas’s citrus industry in the Rio Grande Valley.

The Asian citrus psyllid’s rapid spread and efficiency at transmitting disease make it one of the most critical invasive insect threats to Texas agriculture.

Intensive monitoring and control efforts are in place to slow its advance.

Animals (Non-Bird, Non-Insect)

Texas’s landscapes are under siege by several invasive mammals and other non-insect animals.

These species, often introduced for hunting or by accident, typically have high reproductive rates and few local predators, allowing their populations to boom.

The result is severe damage to crops, rangelands, and native wildlife. From rampant feral hogs tearing up fields to exotic deer competing with native game, invasive animals cause billions in economic losses and ecological harm each year.

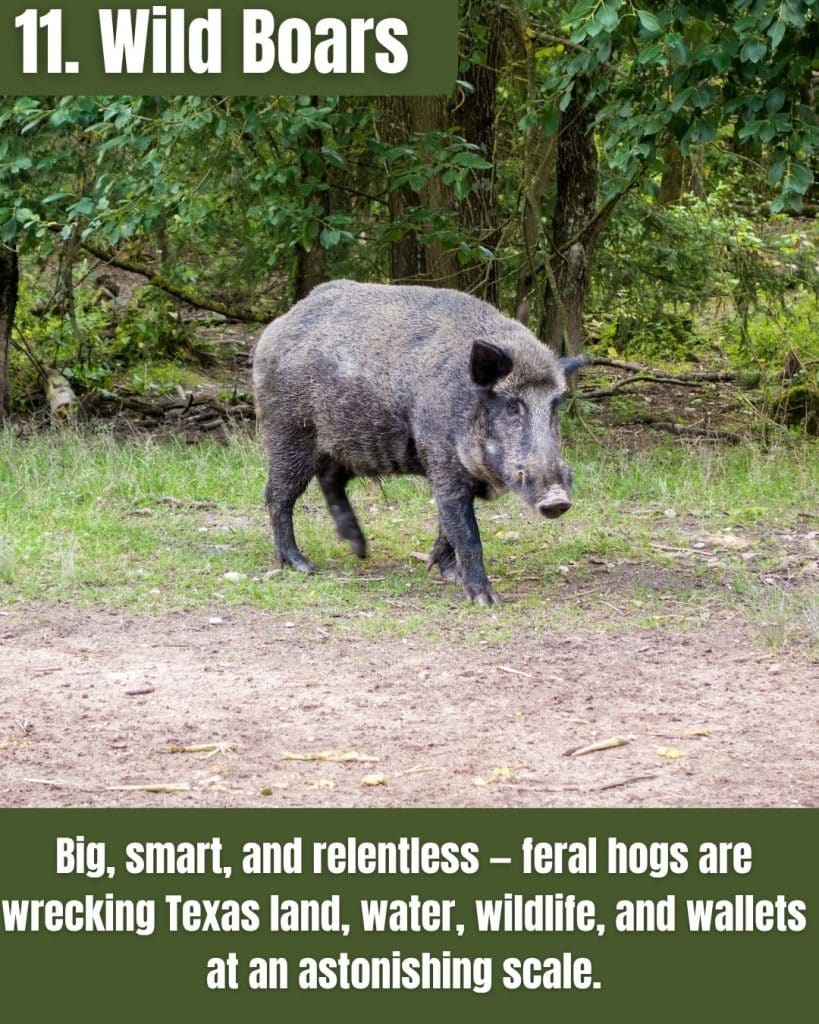

Feral Hog (Sus scrofa)

Often called wild boars, these are domesticated pigs and European wild boars gone wild. Feral hogs have exploded across Texas (over 1.5 million statewide) and are one of the most destructive invasive animals.

They are large (up to 300+ lbs.), travel in groups, and have no natural predators sufficient to control them.

Hogs root up crops, pastures, and native plant communities, causing massive soil erosion and even deforestation with their voracious eating and digging.

Their incessant rooting damages levees and watercourses and can foul streams. They also predate wildlife – hogs will eat ground-nesting bird eggs and young animals.

Beyond habitat damage, feral hogs carry diseases (like pseudorabies, brucellosis) that can spread to livestock.

Conservative estimates put their damage at over $1.5 billion annually in the U.S. (crop losses, property damage, etc.), with Texas bearing a huge share of that.

Controlling feral hogs is a major challenge requiring coordinated trapping and hunting efforts.

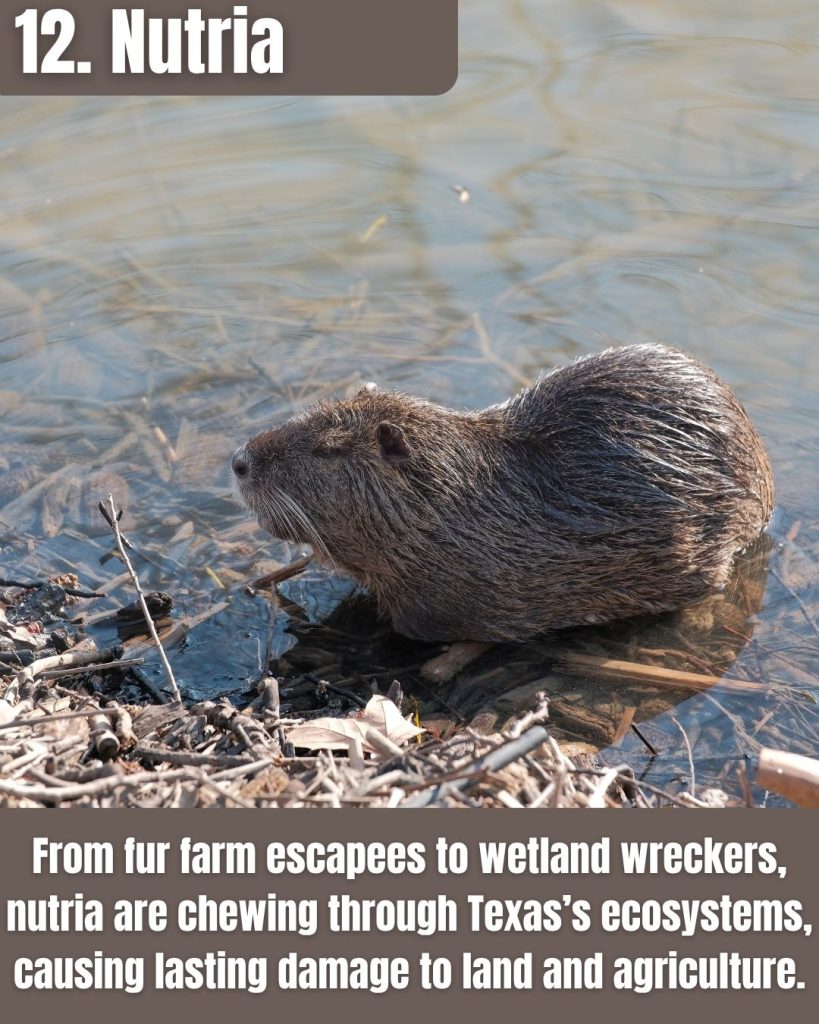

Nutria (Myocastor coypus)

- Escaped fur-farmers: Brought to the U.S. for fur farming, nutria are now a rampant problem in Texas wetlands.

- Vegetation wrecking balls: Can consume up to 25% of their body weight in plants every day, stripping entire marshes.

- Ecosystem engineers (in the worst way): Their burrowing and feeding destroy habitats, erode levees, and damage crops.

A large semiaquatic rodent (20+ lbs) native to South America, Nutria were brought to the U.S. for fur farming and then escaped into the wild.

Now common in East and Central Texas wetlands, nutria are extremely destructive herbivores. They devour aquatic plants and crops voraciously (an adult nutria can eat up to 25% of its weight in vegetation daily.

This feeding habit destroys marshes and wetland habitats, as nutria strip vegetation and leave behind open water and mud.

Their digging of burrows in levees and banks causes erosion and can undermine roads, dikes, and other structures. Nutria have been known to destroy rice, corn, and sugarcane fields.

They also carry diseases and parasites (like tuberculosis and liver flukes) that can affect humans and livestock.

Overall, nutria significantly alter ecosystems by turning vegetated wetlands into open ponds, earning them a spot among Texas’s most damaging invaders.

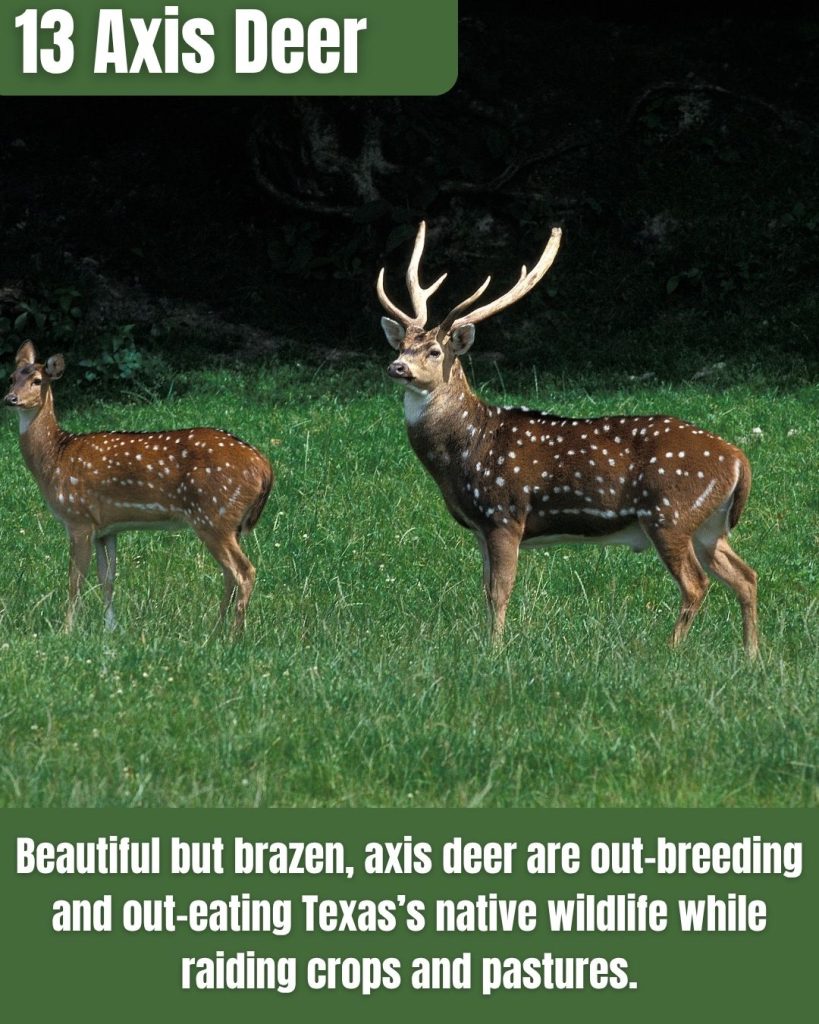

Axis Deer (Axis axis)

- Hill Country takeover: Originally released on Texas ranches in the 1930s, now thriving and expanding in the wild.

- Always in season: Unlike native deer, they breed year-round and bounce back quickly from population dips.

- Too tough for Texas: More disease-resistant than white-tailed deer, giving them an edge in tough conditions and competition.

An exotic deer from India, initially introduced to Texas ranches in the 1930s, the axis deer is now free-ranging in parts of Texas Hill Country.

These spotted deer are similar in size to native white-tailed deer but compete fiercely for the same food and habitat.

Axis deer breed year-round and can increase in number rapidly. Importantly, they show a higher resistance to local diseases than native deer, so while a disease outbreak might reduce white-tailed deer, axis populations continue to thrive.

This allows axis deer to potentially overpopulate and “out-compete” white-tailed deer in some areas . They graze and browse heavily, and Texas farmers report axis deer invading crops and livestock feed, causing damage to gardens and fields.

With tens of thousands now on the landscape, axis deer are the poster child for how introduced game animals can become an invasive problem, threatening both native wildlife and agriculture.

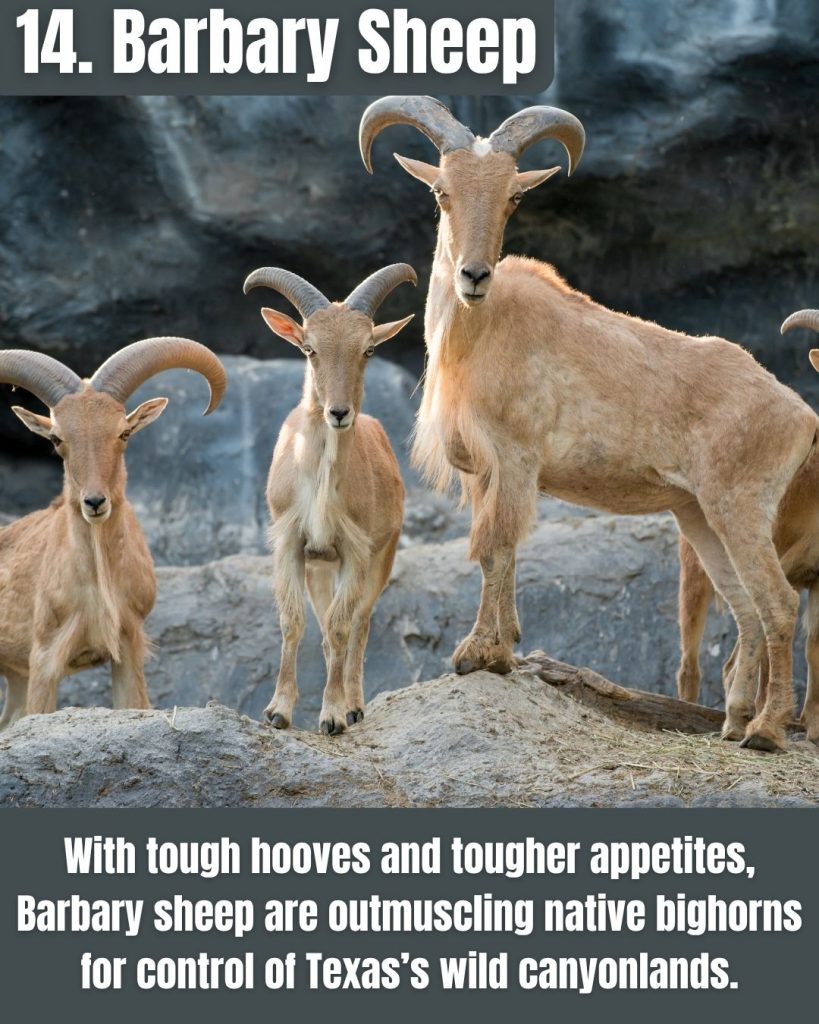

Barbary Sheep (Ammotragus lervia)

- Imported invaders: Released for hunting, now thriving in West Texas’s canyons, right where native bighorns should be.

- Hardy and aggressive: Survive on sparse plants, form large herds, and bully native wildlife out of prime grazing territory.

- Conservation roadblock: Their spread is one of the biggest obstacles to restoring Texas’s desert bighorn sheep.

Also known as aoudad, this North African wild sheep was released in West Texas in the mid-20th century for hunting.

Aoudads have since established robust populations in the rugged canyonlands. They present a major issue by directly competing with native desert bighorn sheep and mule deer for food and space.

Barbary sheep are highly adaptable. They eat a wide range of plants and can survive on sparse vegetation.

They are also aggressive and form large herds, which gives them a competitive edge over the smaller groups of native bighorns.

As a result, efforts to reintroduce Texas’s native bighorn sheep are hampered by aoudads overtaking prime habitat and out-browsing the natives.

Aoudads even occasionally raid farmers’ winter wheat fields, though they are not yet a major agricultural pest.

The presence of these sure-footed invasive sheep in Texas mountains is a significant conservation challenge, requiring active management (usually through hunting) to protect native ungulates.

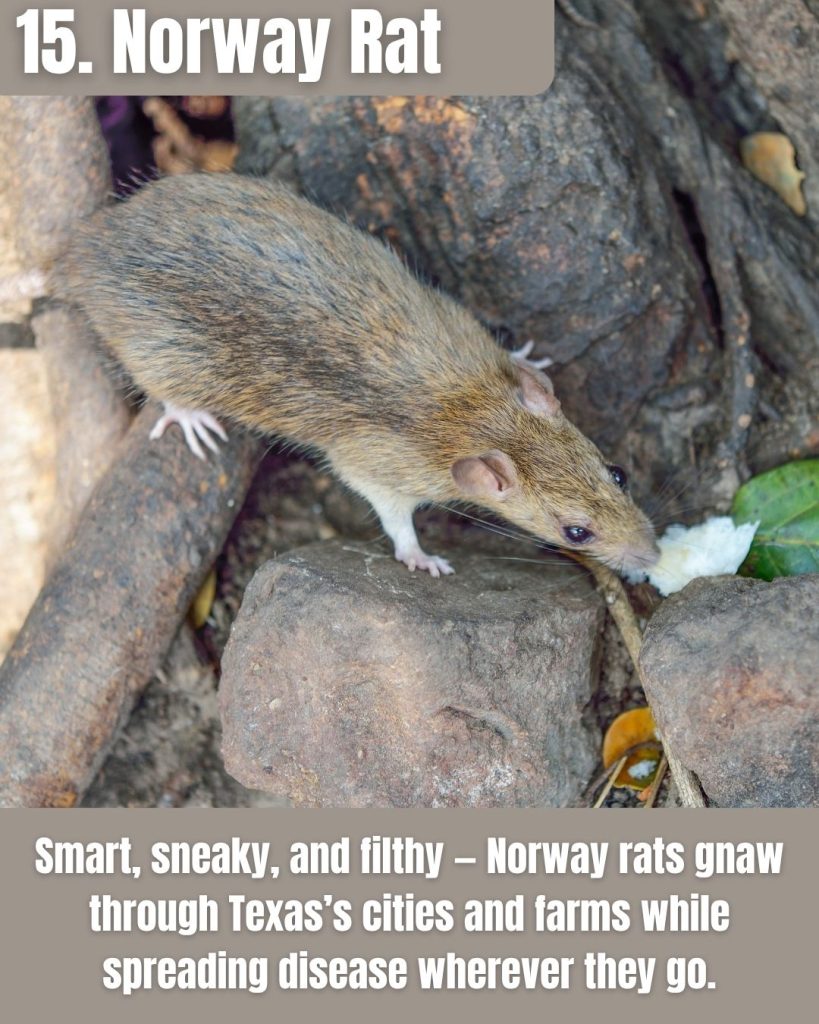

Norway Rat (Rattus norvegicus)

- Adaptable and unstoppable: Thrive in cities, farms, sewers, and buildings — anywhere people are, rats follow.

- Tiny terrors with teeth: Chew through wood, plastic, and electrical wiring, causing fires and property damage.

- Walking biohazards: Known carriers of plague, typhus, salmonella, and other diseases dangerous to humans and livestock.

The Norway rat (brown rat) is a commensal rodent originally from Asia, now found statewide in Texas, especially in urban and farm areas.

These rats are prolific breeders and adapt well to human environments. In the wild they disrupt ecosystems by preying on native insects, eggs, and small animals.

Economically, Norway rats are a serious pest: once established, they cause frequent property destruction, gnawing on wood, plastic, and electrical wires .

They invade poultry houses and farms, eating stored grains and even attacking young chickens or livestock (reports exist of rats killing young chicks and even piglets).

Perhaps most concerning, Norway rats carry many diseases; they are vectors or reservoirs for pathogens causing bubonic plague, typhus, salmonellosis, rat-bite fever, and more.

As fast breeders that are adept at avoiding traps, Norway rats remain one of the most persistent and harmful invasive mammals affecting Texas’s urban infrastructure and public health.

Plants (Terrestrial)

Texas’s land ecosystems face invasions by numerous non-native plants. These invasive plants often grow faster and reproduce more prolifically than natives, allowing them to overrun habitats.

They choke out native flora, alter soil chemistry, increase wildfire risks, and reduce habitat quality for wildlife.

Humans introduced many of these species (as ornamentals, for erosion control, etc.), only to have them escape cultivation.

Now, Lone-Star land managers see forests, rangelands, and prairies transformed by invasive trees, vines, and grasses. Below are five of the most problematic terrestrial invasive plants in Texas:

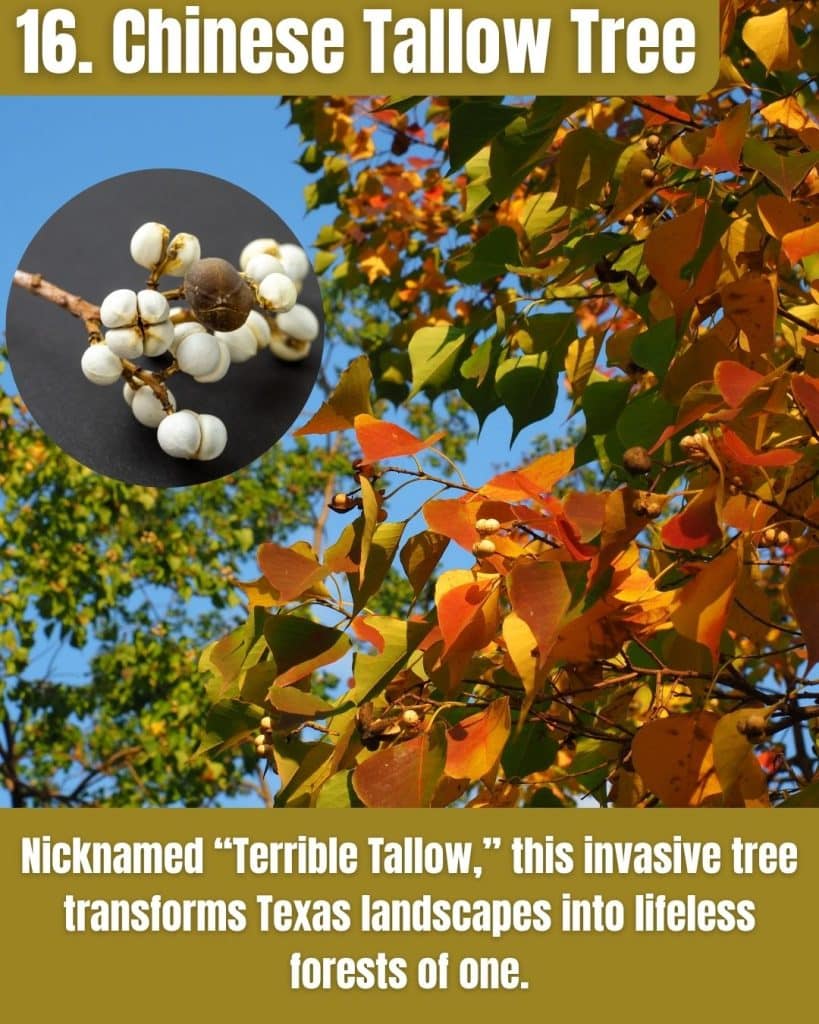

Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica sebifera)

Nicknamed “Popcorn tree” for its white seeds, this ornamental from Asia has become one of Texas’s worst invasive trees.

Chinese tallow is highly adaptable and invades forests, prairies, and wetlands, often forming dense monocultures.

It spreads by both seeds and root sprouts. Once established, tallow trees can quickly dominate an area until they’re the only tree species present.

They also may alter soil chemistry to their advantage, making it harder for other plants to grow. Texas foresters have observed tallow stands replacing native bottomland trees and coastal prairie vegetation, earning it the moniker “Terrible Tallow”.

Aside from ecosystem impacts, tallow trees can be costly for landowners to remove due to their prolific saplings.

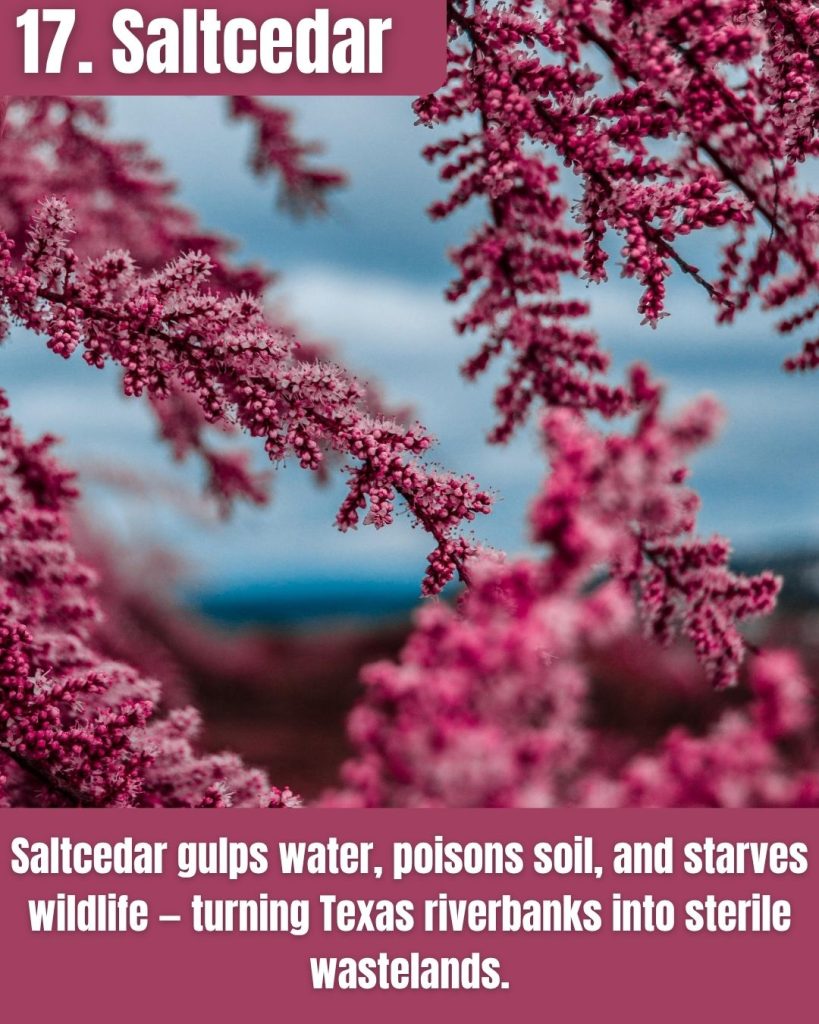

Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.)

- Thirsty invaders: One plant can gulp down 200 gallons of water a day, drying up wetlands and rivers.

- Soil saboteurs: Leach salt from their leaves into the soil, making it toxic for native plants to grow.

- Biodiversity busters: Replace rich native habitats with poor, protein-light thickets that support only a handful of bird species.

A group of shrubby trees from Eurasia that have infested riparian areas across West and Central Texas. Saltcedars (also called tamarisks) are water-hungry and extremely aggressive.

A single saltcedar can consume up to 200 gallons of water per day under hot conditions, draining groundwater and drying up wetlands. These plants have long taproots that tap into water tables and can survive drought.

Saltcedar also excretes salt from its leaves, depositing salt into the surrounding soil and inhibiting native plant growth.

The result is rivers and lake shores lined with nearly pure stands of saltcedar, crowding out willows, cottonwoods, and other native plants.

Wildlife is impacted as well. Saltcedar thickets provide little nutritious forage (their foliage is low in protein) and support far fewer native bird species compared to native vegetation (only about 4 bird species in saltcedar vs. 150+ in native riparian habitat).

Saltcedar’s spread has lowered groundwater, increased soil salinity, and even increased wildfire fuel in many Texas watersheds.

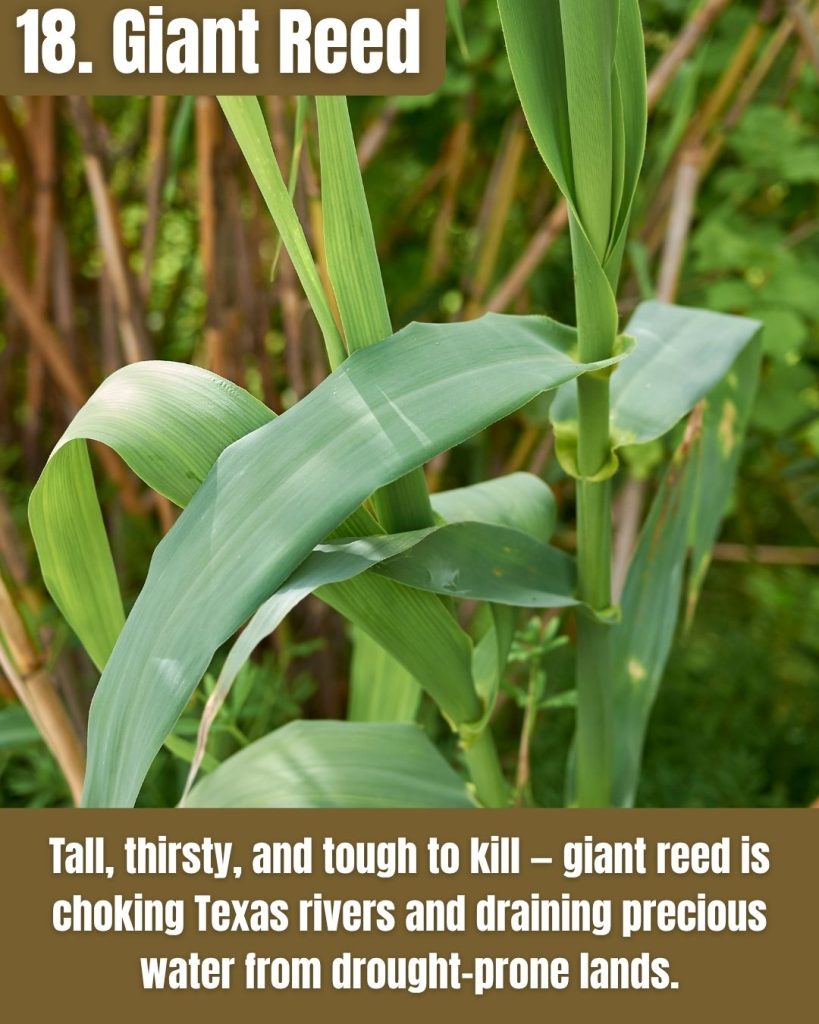

Giant Reed (Arundo donax)

- Bamboo impersonator: Grows up to 20 feet tall, creating thick cane-breaks that push out native river plants.

- Water hog: Sucks up tons of water from streams and ditches, worsening drought and lowering flow.

- Fire and law hazard: Fuels wildfires and blocks visibility along the Rio Grande, hampering border enforcement efforts.

A towering grass introduced from the Old World, giant reed (also called Arundo or carrizo cane) grows in dense cane-breaks along Texas rivers and roadsides.

Resembling bamboo, it can reach 20 feet tall and spreads aggressively in wet areas. Giant reed thrives on riverbanks and irrigation ditches, where its rapid growth and extensive rhizome root system allow it to out-compete native plants.

It often forms monoculture thickets that choke out riparian vegetation. This plant also slurps up water; large stands can reduce stream flow and worsen drought impacts.

Additionally, giant reed provides poor habitat for wildlife and can fuel intense wildfires when dry. Along the Rio Grande, infestations of Arundo have been targeted for removal because they impede law enforcement visibility and consume precious water.

Its resilience and difficult removal (it resprouts from fragments) make giant reed a persistent invasive in Texas.

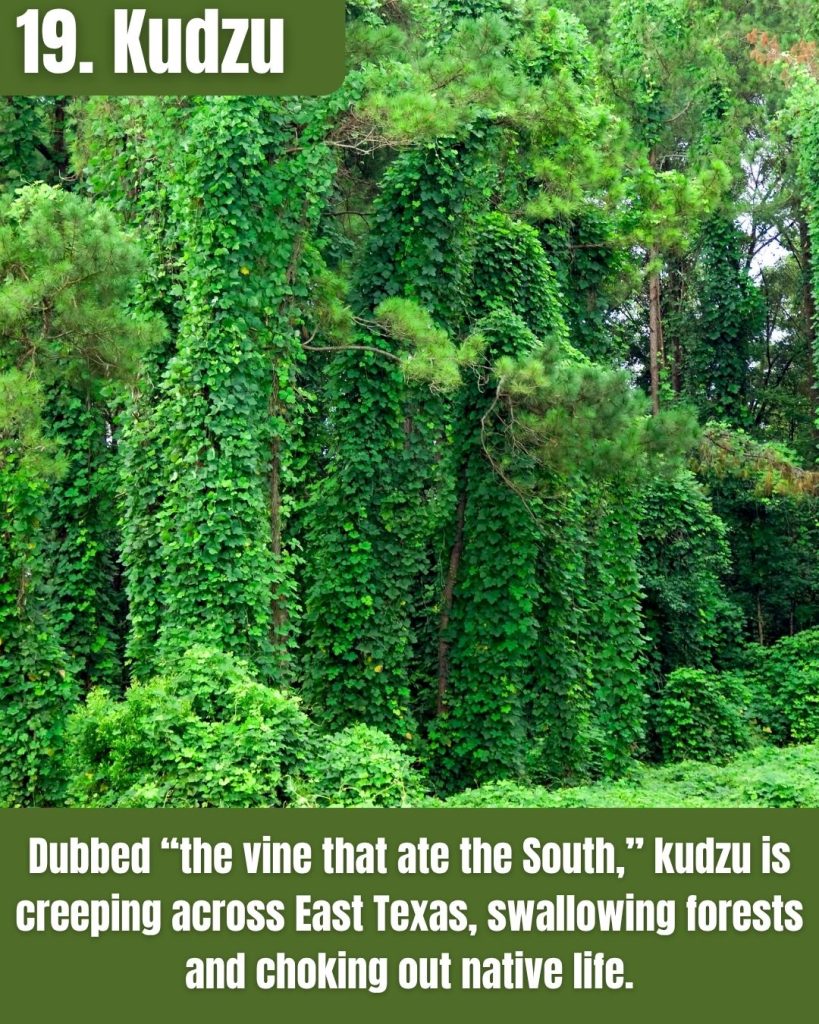

Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata)

- Grows like wildfire: Can grow up to a foot per day, engulfing trees, power lines, and buildings in green curtains.

- Smothers everything: Blocks sunlight and suffocates forests beneath its dense, fast-growing vines.

- Hard to kill, easy to spread: Deep roots and nitrogen-fixing ability make kudzu both persistent and soil-altering.

Famously known as “the vine that ate the South,” kudzu is present in East Texas and poses a constant threat.

This vine, introduced from Asia for erosion control, is a rapid-growing climber that can grow a foot per day in summer.

Kudzu vines will smother entire forests. They climb over trees, shrubs, and structures, covering them in a blanket of dense foliage. Under kudzu’s shade, native plants die from lack of sunlight. Kudzu also fixes nitrogen, which can alter soil nutrient balance.

While not yet as widespread in Texas as in some southeastern states, there are significant infestations in East Texas forests and along roadsides.

If left unchecked, kudzu can turn biodiverse woodlands into vine-draped wastelands. Control is difficult, requiring persistent herbicide application or grazing; the vine’s extensive root system makes it hard to eradicate.

Texas includes kudzu on its list of prohibited noxious plants due to the severe ecological and economic damage it can cause.

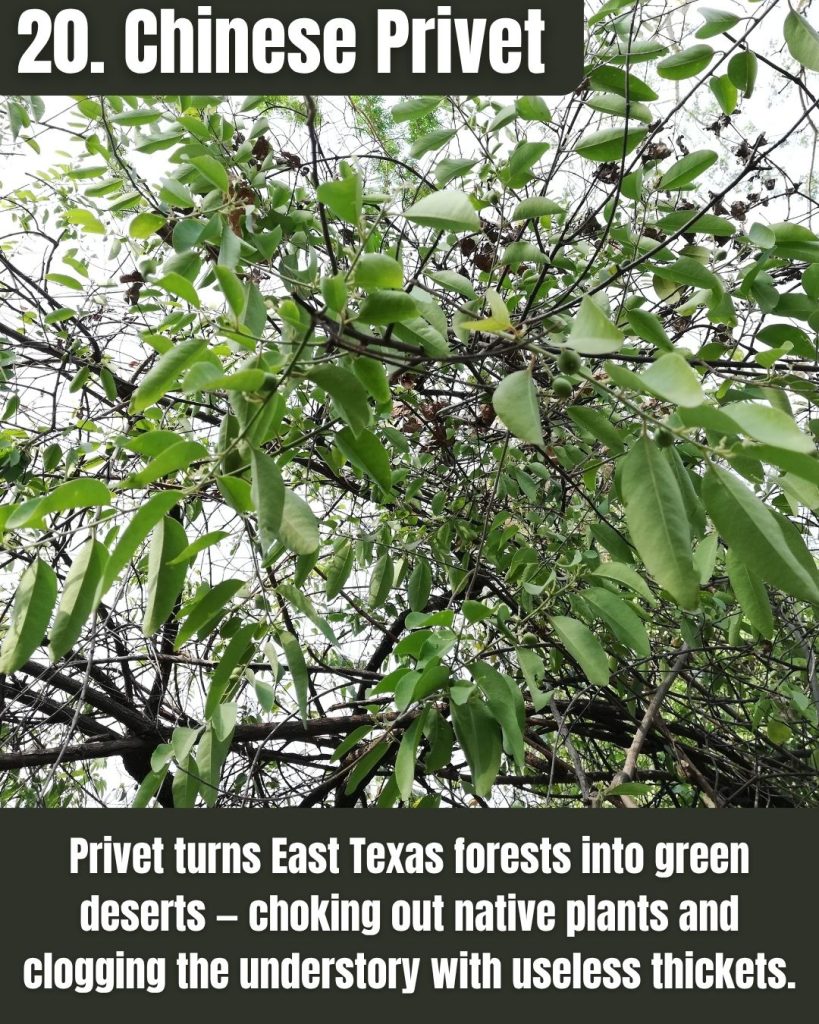

Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense and other Ligustrum spp.)

- Shade-loving invader: Thrives under forest canopies, forming thick understory thickets that block out native plants.

- Bad berries, big spread: Birds eat the berries but gain little nutrition — and spread seeds far and wide.

- Takes over fast: Once rooted, privet is hard to remove and often requires repeated herbicide and cutting to control.

These are evergreen shrubs introduced from Asia as landscaping plants, now invasive in Texas woods and fields. Chinese privet and its relatives form thick, impenetrable thickets in the understory of forests.

They tolerate shade well, enabling them to take over beneath forest canopies. As privet spreads, it out-competes virtually all other understory vegetation, creating a monoculture.

This reduces plant diversity and alters wildlife habitat (few native animals eat privet berries, and dense thickets can impede movement of larger animals).

Privet invasions are especially problematic in East Texas bottomland forests and urban greenbelts.

They also invade fence rows and stream banks. Birds do eat the berries and disperse the seeds, which has facilitated privet’s spread.

Land managers note that once privet is established, it can dominate an area and is very hard to remove. Consistent cutting and herbicide treatment are usually required to reclaim native plant communities from these hardy invasive shrubs .

Waterways (Fish and Aquatic Plants)

Texas’s rivers, lakes, and coastal waters are under threat from various invasive fish, invertebrates, and aquatic plants.

These aquatic invaders can out-compete native species for food and space, alter water quality, and cause costly damage to infrastructure.

Boaters, anglers, and the aquarium trade have inadvertently introduced many of these species to Texas waterways.

Once established, they often spread rapidly downstream or between water bodies. The following five invasives are among the most damaging to Texas’s aquatic ecosystems and fisheries:

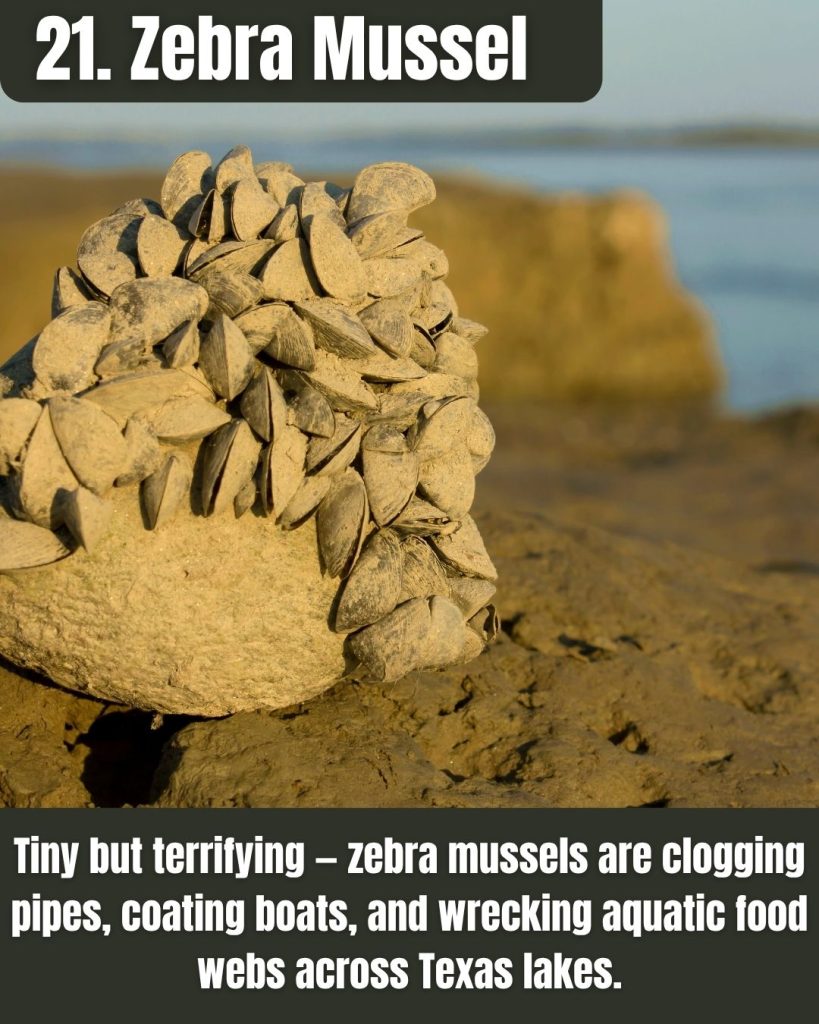

Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorph)

- Reproductive powerhouse: A single female can spawn up to a million eggs a year, rapidly overrunning waterways.

- Infrastructure nightmare: Clog pipes, pumps, and water systems, causing expensive damage to cities and power plants.

- Aquatic ecosystem disrupters: Filter out plankton and nutrients, starving native fish and invertebrates.

A small freshwater mussel with black-and-white striped shells, originally from Eurasia. Zebra mussels were first found in Texas in 2009 and have since infested numerous lakes and rivers.

They have explosive reproduction. A single female can release up to a million eggs per year. The mussels attach in massive clusters to any hard surface.

As a result, they clog water intake pipes, pumps, and valves, posing huge problems and maintenance costs for municipal water supplies and power plants.

Recreationally, they encrust boat hulls, docks, and even native mussels (often killing them). Ecologically, zebra mussels are filter feeders that can clear out plankton and nutrients from the water, robbing native fish and invertebrates of food.

Their invasion has already altered aquatic food chains in Texas lakes. Because of these impacts, Texas has strict boat-cleaning rules to prevent their spread, as zebra mussels are considered one of the most destructive aquatic invaders in the state.

Giant Salvinia (Salvinia molesta)

- Grows at warp speed: Can double in size weekly, forming thick mats that choke lakes and bayous.

- Kills from the top down: Blocks light and oxygen, smothering fish, plants, and entire aquatic ecosystems.

- Hitchhiker hazard: Spreads easily on boat props and trailers, making accidental infestations common.

A floating fern from South America that has become a notorious weed on Texas water bodies. Giant salvinia forms thick mats of floating vegetation that double in size about every week under optimal conditions, making it one of the fastest-growing aquatic plants.

These mats block sunlight and oxygen in the water, causing die-offs of submerged plants and animals. Native fish and waterfowl lose food and habitat as salvinia blankets the surface.

When the plant dies and decomposes, it further depletes oxygen, leading to fish kills . Giant salvinia has infested several East Texas lakes (like Caddo Lake) and bayous, sometimes completely covering coves and boat lanes.

Boaters can unintentionally spread it on their props and trailers. Because it can render lakes unusable for recreation and devastate ecosystems, Texas Parks and Wildlife has mounted aggressive efforts to contain and eradicate giant salvinia, including biological control with salvinia-eating weevils.

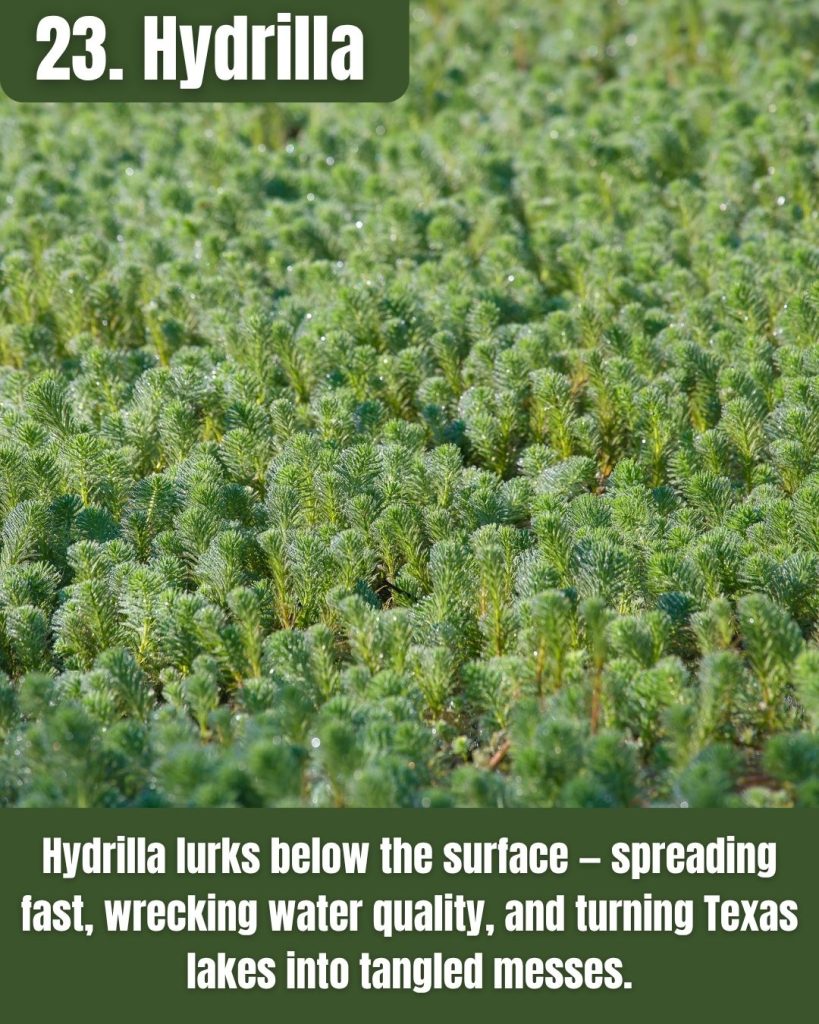

Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata)

- Aquarium escapee: Grows up to 30 feet long, forming dense thickets that block sunlight and choke lakes.

- Chemical troublemaker: Alters water pH and oxygen levels, stressing or killing fish during heavy infestations.

- Recreation ruiner: Snarls boat props, clogs waterways, and turns lakes into underwater jungles.

A submerged aquatic plant from Asia, popular in aquariums, that has invaded many Texas freshwater systems.

Hydrilla grows underwater in long strands that can reach the surface, up to 30 feet tall in deep water. It spreads rapidly via fragments and tubers in the soil.

Hydrilla often forms dense underwater thickets or mats at the surface, blocking sunlight and impeding water flow. It can even alter water chemistry; heavy infestations can cause pH swings and deplete oxygen at night, stressing fish.

For boaters and swimmers, hydrilla is a hazard. Its tough stems tangle in propellers and make waterways impassable.

Lakes like Lake Austin have required costly treatments to control hydrilla. While hydrilla can provide some habitat for fish when sparse, its tendency to overgrow makes it ecologically harmful and a management nightmare.

Aquarium dumping and boat traffic have been key factors in its spread, so Texas promotes public awareness (“Don’t dump your tank” and cleaning boats) to help combat this invasive plant.

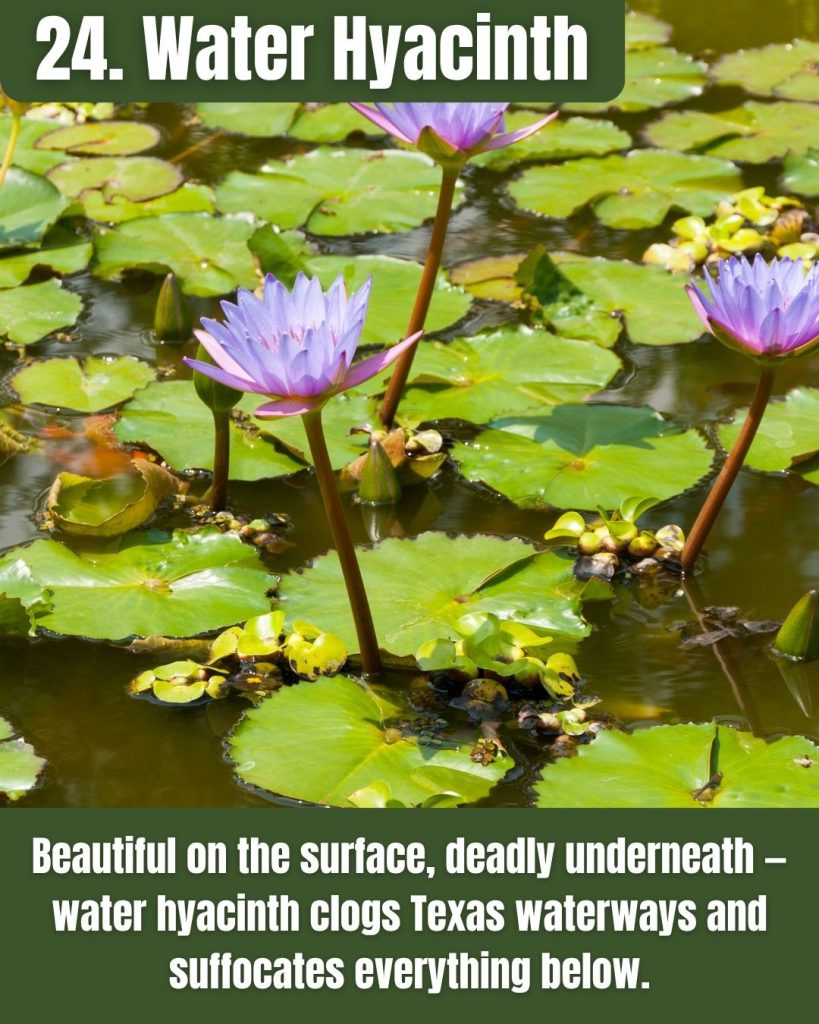

Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes)

- Pretty but problematic: Introduced for its flowers, it now chokes rivers, lakes, and bayous with floating mats.

- Oxygen thief: Blocks sunlight and gas exchange, suffocating aquatic life and killing submerged plants.

- Mosquito motel: Dense mats create stagnant water, perfect for mosquito breeding and disease spread.

A floating water plant native to the Amazon basin, introduced for its attractive purple flowers. In Texas, water hyacinth has proliferated in warm waters and become a serious pest in bayous, rivers, and reservoirs.

The plant forms rosettes of thick, waxy leaves with spongy air-filled stems, allowing it to float. It can multiply rapidly, forming expansive mats over the water’s surface.

Like giant salvinia, water hyacinth blocks sunlight and oxygen exchange, leading to die-off of submerged vegetation and low oxygen for fish.

Large infestations can hinder boating, fishing, and irrigation by clogging waterways . Additionally, stagnant mats of hyacinth create breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

Water hyacinth has been a particular problem in Southeast Texas (e.g. the San Jacinto River and Houston bayous), where constant removal efforts are needed.

Although freezing temperatures can knock it back, the plant often regrows from protected pockets. Due to its pretty appearance, it was spread by gardeners, but it is now recognized as a destructive invader of Texas waters.

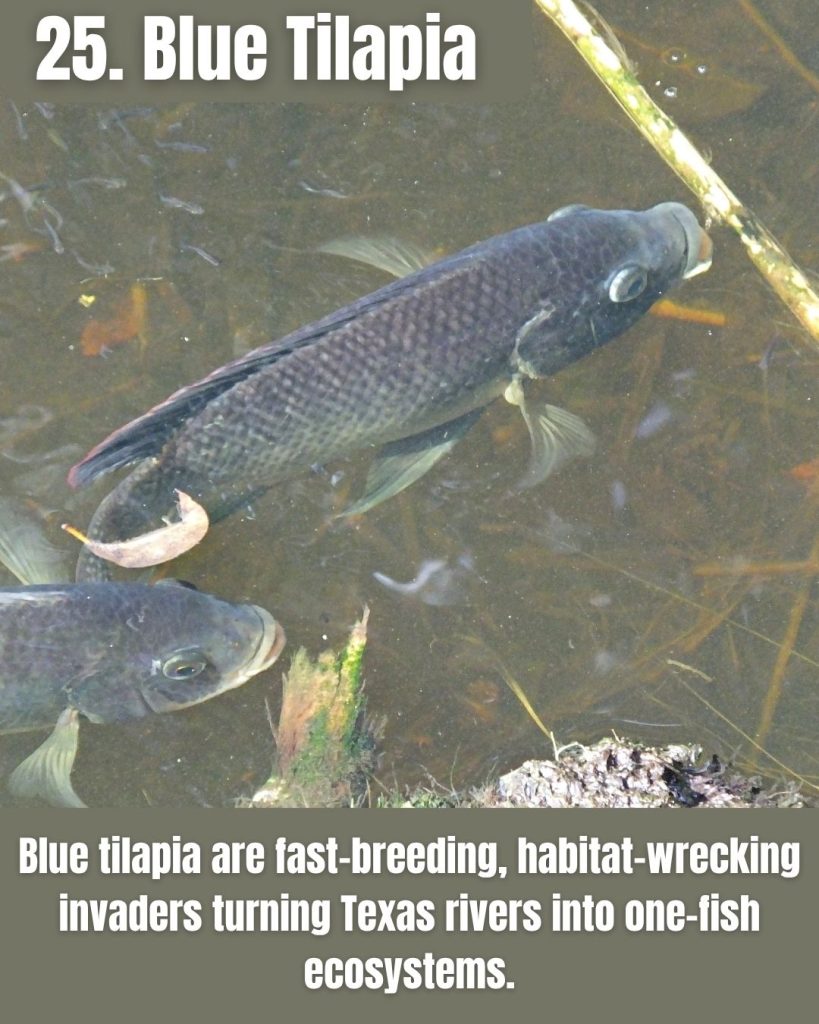

Blue Tilapia (Oreochromis aureus)

- Breeding nonstop: Females can spawn over 1,000 fry at a time and reproduce year-round.

- Ecosystem bullies: Clear vegetation for nests and outcompete native fish for food and space.

- Hardy invaders: Tolerant of poor water quality and cold snaps, making them tough to eradicate once established.

An African cichlid fish that has invaded many Texas lakes and rivers. Originally introduced (sometimes intentionally stocked to control weeds or for sport), blue tilapia have established wild populations in the San Antonio, Brazos, and other river basins.

These fish are hardy and prolific breeders. A female can produce over a thousand fry per spawn and breed year-round.

Blue tilapia are voracious, omnivorous feeders that consume plants, algae, insects, and small fish, thereby depleting the food and habitat that native fish and even freshwater mussels rely on.

They also clear large areas of aquatic vegetation to build their nest colonies, further altering habitats.

In invaded streams, biologists have observed shifts in fish communities, with tilapia outcompeting and reducing populations of native species.

Because they tolerate poor water quality and even occasional cold snaps, tilapia have spread quickly once introduced. They can become the dominant fish, which is a big concern for biodiversity and fisheries. Texas classifies tilapia as harmful exotic fish.

It is illegal to possess or transport live tilapia without a permit, and anglers are encouraged not to release them if caught (to prevent further spread). Controlling an established tilapia population is difficult, so preventing their introduction is key.

Thank you for reading!

Thank you to the following organizations for their valuable contribution:

Texas Parks & Wildlife Department; TexasInvasives.org; Texas A&M AgriLife Extension; U.S. Department of Agriculture (APHIS); U.S. Geological Survey; San Antonio River Authority; University research programs, among others.