Imagine hiking a Michigan trail or launching a boat on a clear inland lake… and realizing the biggest threat isn’t a storm or a bad day of fishing. It’s a quiet invasion.

Michigan’s forests, wetlands, and Great Lakes shoreline are packed with life—but invasive species keep barging in, taking over habitat, and throwing the whole system off balance.

From mussels that clog pipes to plants that swallow riverbanks, here are 25 invasive troublemakers causing real problems across Michigan—and what to watch for.

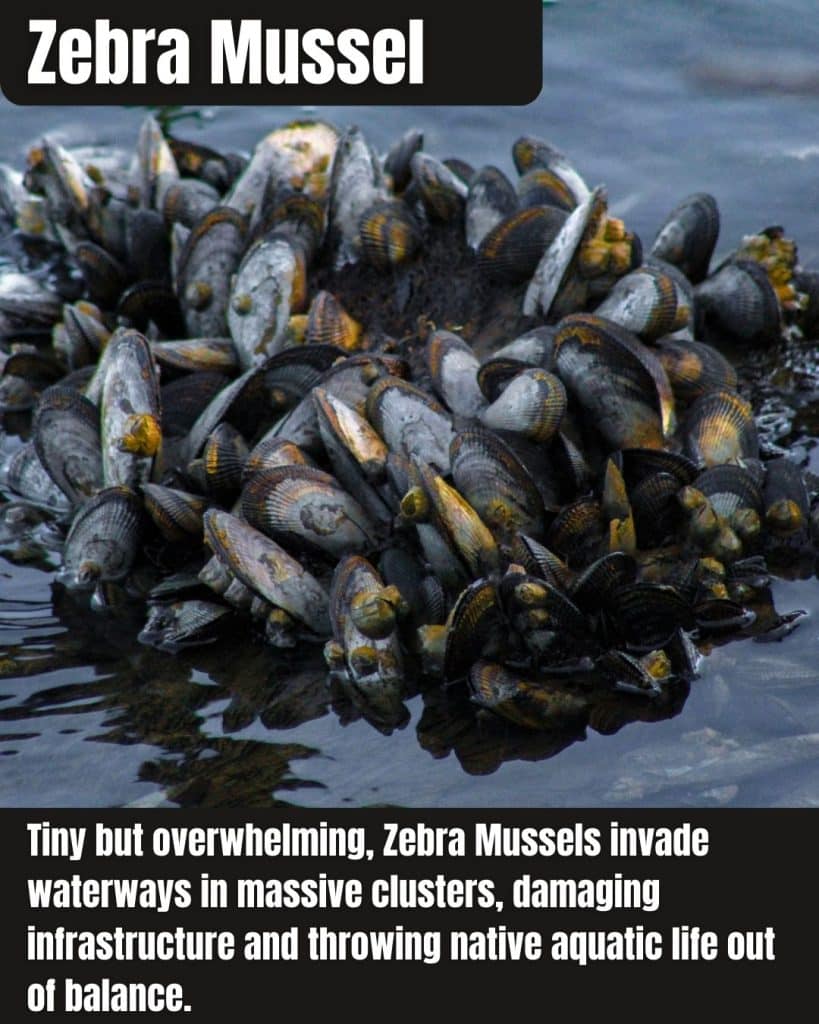

1. Zebra Mussels

- Clogs infrastructure: Pipes, intake screens, and marina equipment can get packed with shells.

- Smothers native mussels: They attach in piles, stressing or killing Michigan’s native species.

- Sharp shoreline hazard: Beaches and shallow areas can turn into “shell beds” that cut feet and paws.

Zebra mussels are small, but in Michigan waters they act like a living, multiplying coating. Once they get established, they attach to almost anything hard—docks, rocks, boat hulls, water intakes—and they don’t stop.

The best defense is prevention: Clean, Drain, Dry boats and gear, and never move water or bait between lakes.

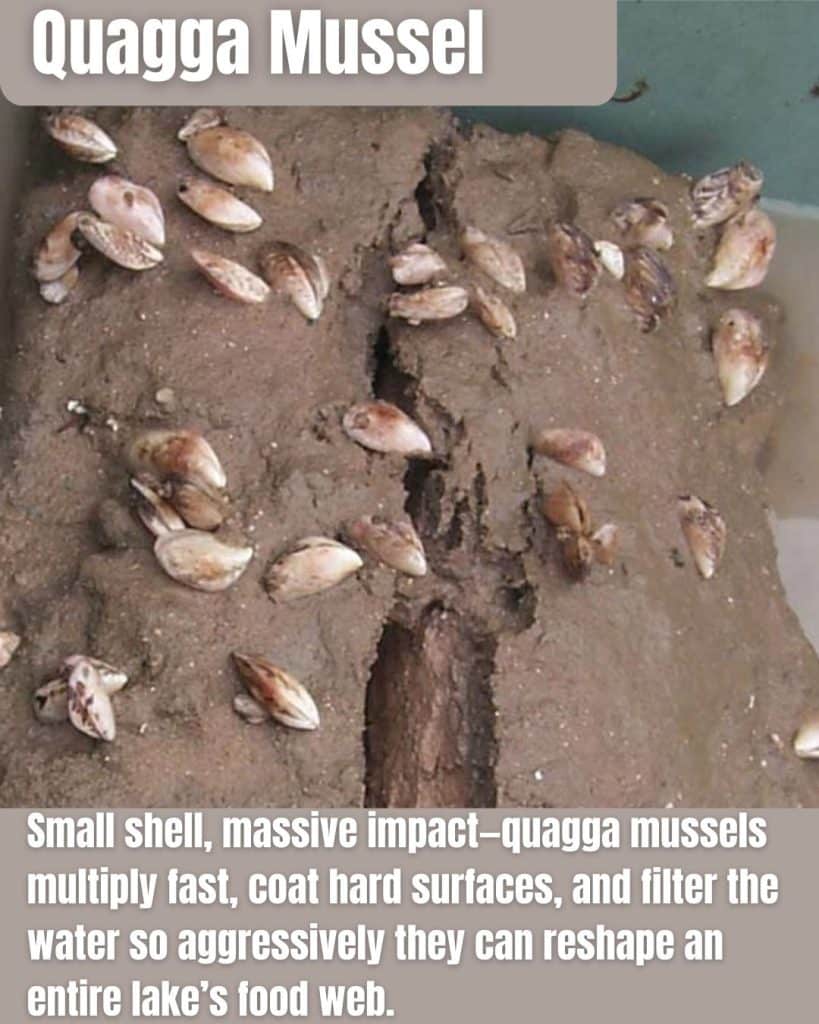

2. Quagga Mussel

- Deep-water invader: Unlike zebra mussels, quaggas can thrive deeper and spread wider.

- Food web disruption: They filter out plankton that young fish and native species depend on.

- Costs add up: Maintenance and cleanup can hit water systems, marinas, and shoreline communities.

Quagga mussels are one reason Michigan’s Great Lakes ecosystem keeps shifting. They filter massive amounts of water, which can sound “good” until you realize they’re stripping the base of the food chain and reshaping fish habitat.

They spread the same way zebra mussels do—by hitchhiking—so boat and gear hygiene is everything.

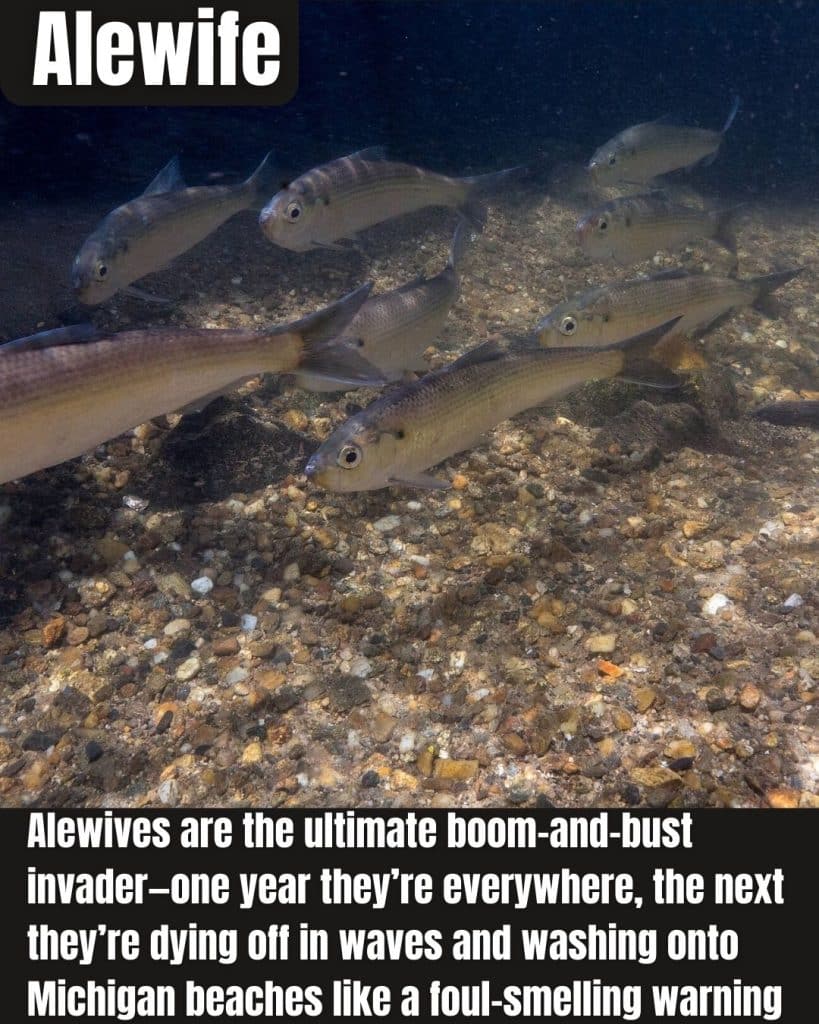

3. Alewife

- Boom-and-bust fish: Their populations can surge and crash, creating chaos for the lake food web.

- Outcompetes natives: They can pressure native forage fish by competing for food.

- Beach nuisance: When die-offs happen, shorelines can get littered with dead fish.

Alewives are one of those invasives that don’t just “show up.” In Michigan’s Great Lakes history, they’ve been tied to massive swings in the system—sometimes exploding in number, sometimes crashing and washing up by the truckload.

Management in big waters is complicated, but the everyday rule stays simple: don’t move live fish or bait from one waterbody to another.

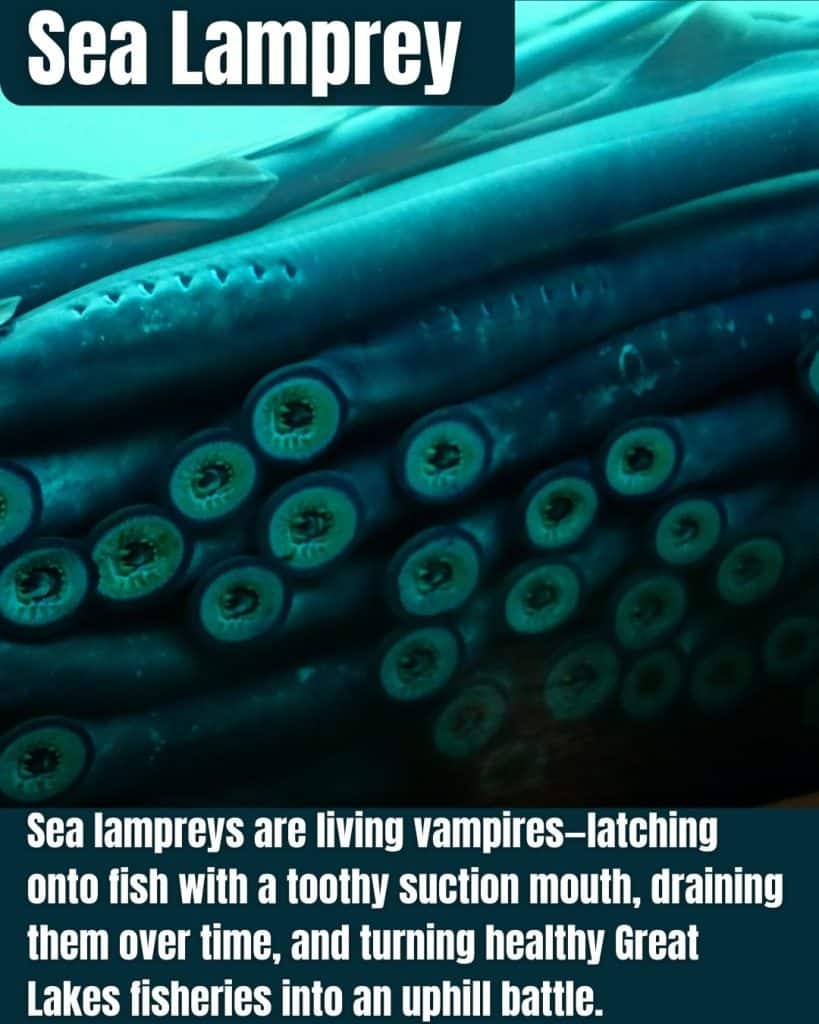

4. Sea Lamprey

- Parasite predator: Attaches to fish and feeds on blood and body fluids.

- Major fishery impacts: Can reduce populations of valuable sport and native fish.

- Spreads via connected waters: Streams and tributaries can act like invasion highways.

Sea lamprey look like something out of a horror movie… because they kind of are. They latch onto fish with a round, toothy mouth and weaken or kill them over time.

Michigan’s Great Lakes control efforts are a long-term battle, and it shows how one invader can reshape an entire region’s fishing future.

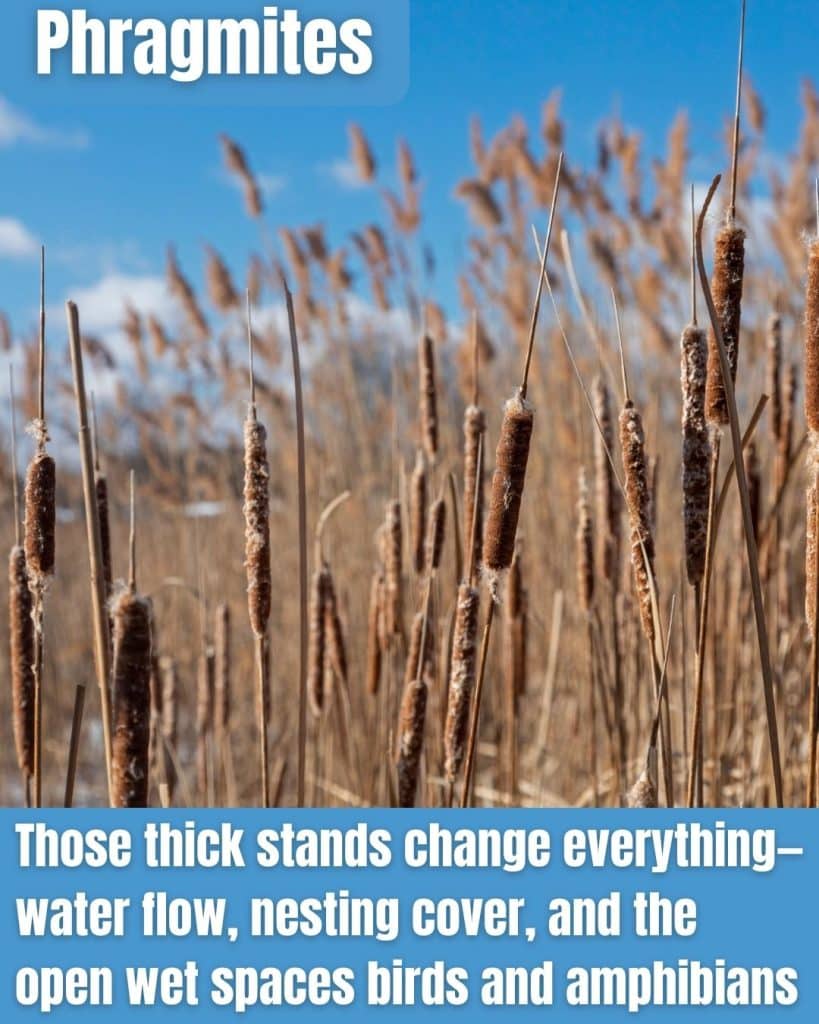

5. Phragmites (Common Reed)

- Wetland wall-builder: Forms tall, dense stands that crowd out native plants.

- Wildlife habitat loss: Many native birds and amphibians don’t use it the same way they use native marsh plants.

- Hard to remove: It spreads by seed and rhizomes, and rebounds after cutting.

Phragmites is one of the most “seen everywhere” invasives in Michigan—especially along roadsides, ditches, shorelines, and wetlands. It grows like a living fence and slowly squeezes out the diversity that makes marshes work.

Control usually takes a plan (often herbicide + follow-up), because cutting alone can make it come back thicker.

6. Round Goby

- Egg eater: Raids nests and eats eggs of native fish, hurting reproduction.

- Aggressive competitor: Pushes native bottom-dwellers out of prime rocky habitat.

- Spreads by hitchhiking: Can move in bait buckets, bilge water, and on gear between waters.

In Michigan, the round goby is a true “bottom bully.” It hugs rocky areas, gobbles up eggs, and takes over the best spawning and feeding real estate.

If you fish the Great Lakes or connected waters, this is one of the invasives you’re most likely to run into. The key prevention message is simple: never dump bait, and always drain water from boats and livewells before you leave.

7. Emerald Ash Borer

- Fast ash killer: Infestations can kill trees in just a few years.

- Neighborhood canopy loss: Streets, parks, and woods can lose shade quickly.

- Firewood spread: Moving ash firewood is one of the easiest ways to help it travel.

Michigan has lived the emerald ash borer disaster up close. Once it’s in a tree, larvae tunnel under the bark and cut off the tissues that move water and nutrients.

If there’s one “do this every time” rule in Michigan, it’s don’t move firewood. Buy it where you burn it.

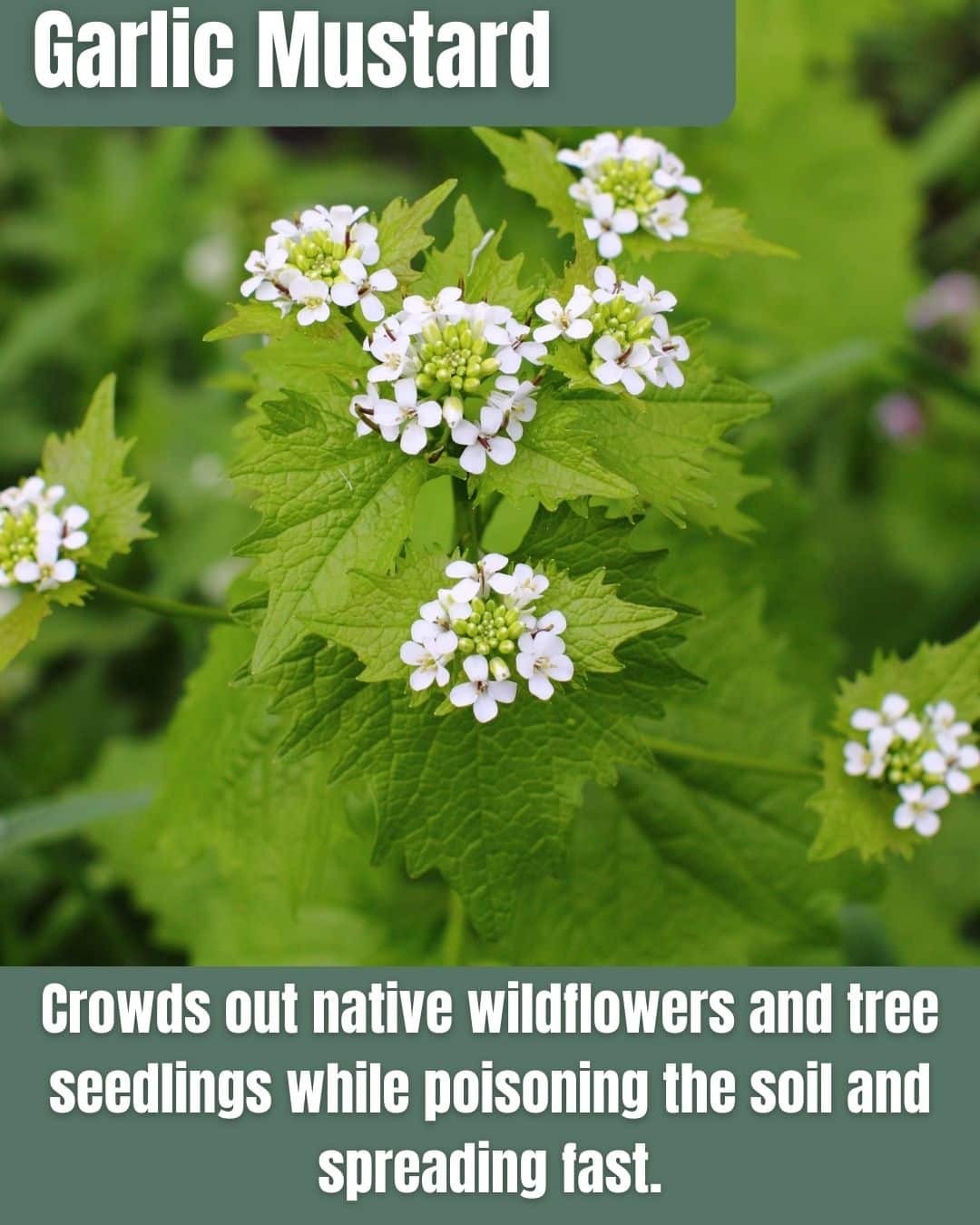

8. Garlic Mustard

- Spring takeover: Forms carpets that crowd out native wildflowers.

- Soil disruption: Interferes with soil fungi many native plants rely on.

- Seed staying power: Seeds can remain viable for years, making follow-up essential.

Garlic mustard is a classic Michigan woods invader—especially along trails, forest edges, and shaded parks. It pops early, shades out spring wildflowers, and keeps coming back if it’s allowed to seed.

Hand-pulling works best before flowers turn into seed pods. Bag it if it’s flowering, because pulled plants can still ripen seed.

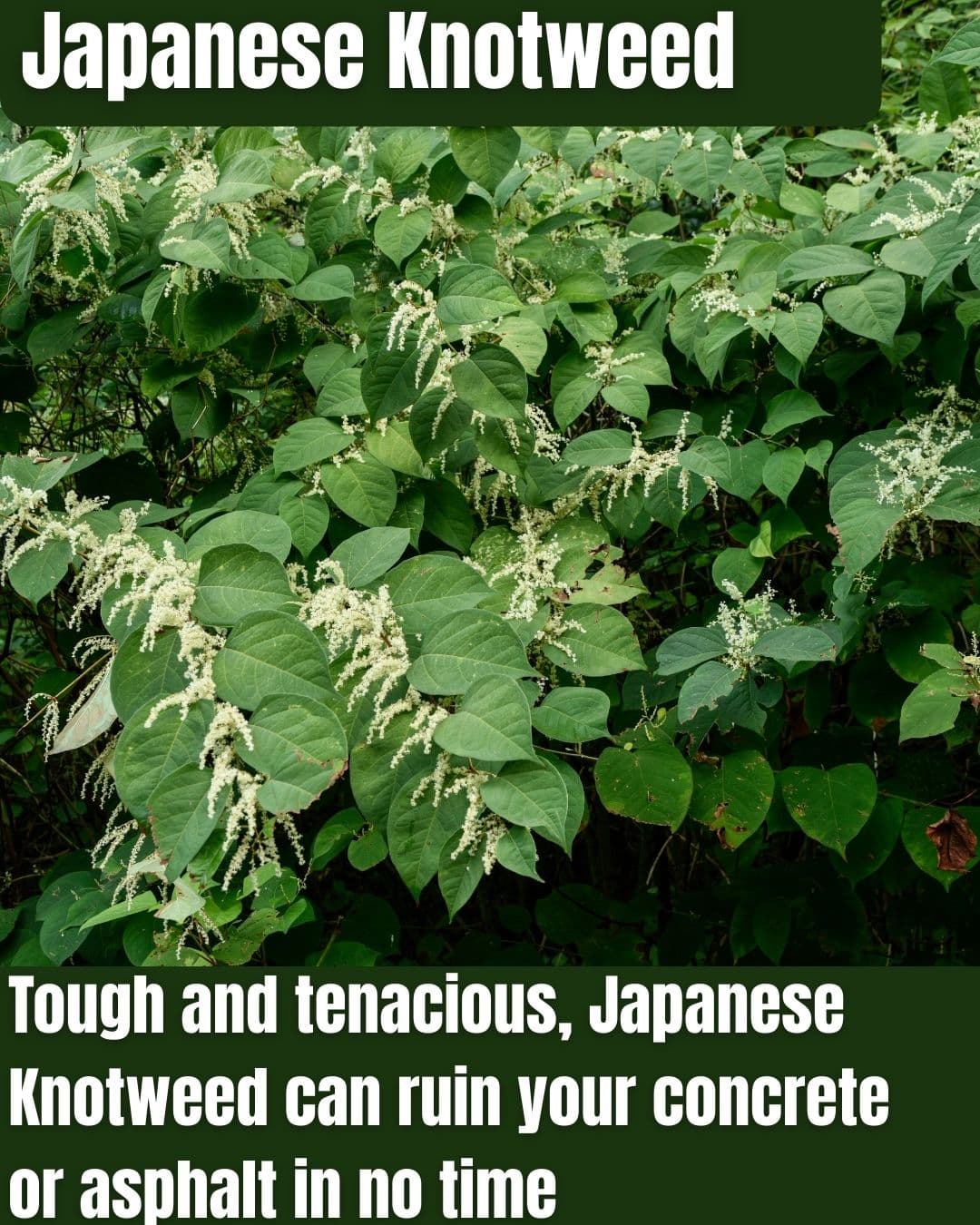

9. Japanese Knotweed

- Riverbank bully: Forms dense walls that crowd out native plants.

- Fragment regrowth: Small pieces of root or stem can start new infestations.

- Infrastructure headaches: Can complicate maintenance along roads, drains, and stream corridors.

Japanese knotweed loves disturbance, and Michigan has plenty of it—streambanks, ditches, road edges, construction sites, and flood-prone areas. Once it gets a foothold, it builds thick stands that block light and push everything else out.

For most homeowners, the reality is this: it usually takes a multi-year plan, and careless cutting can spread it if fragments get moved.

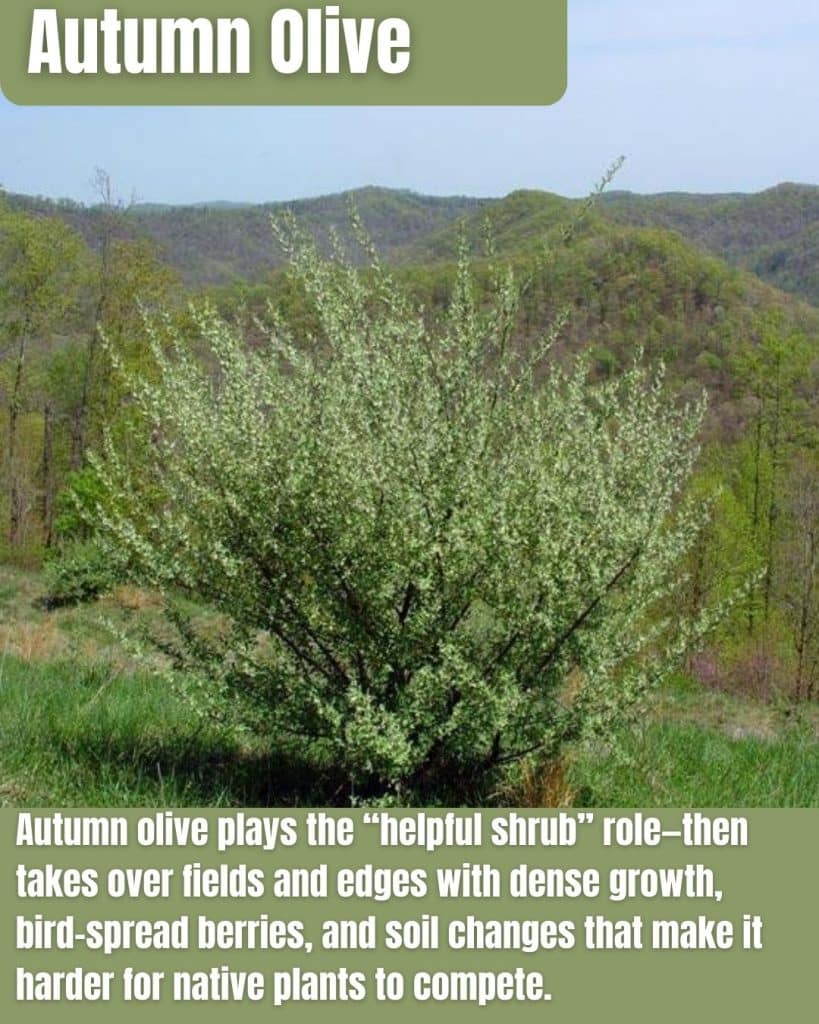

10. Autumn Olive

- Field and edge takeover: Forms dense shrubs that push out native plants.

- Bird-spread seeds: Berries help it travel far from where it was planted.

- Changes soil: Can alter nitrogen levels, giving itself an advantage over natives.

Autumn olive was planted for “wildlife habitat” and windbreaks, but in Michigan it often turns into a thick, thorny problem—especially along old fields, roadsides, and sunny woodland edges.

Cutting alone usually leads to resprouting. Long-term control often means cutting and treating regrowth so it can’t rebound.

11. Spotted Knapweed

- Dry-site invader: Thrives in sunny, disturbed places like roadsides and fields.

- Outcompetes natives: Crowds out grasses and wildflowers that wildlife needs.

- Spreads by seed: Seeds can move on tires, mowers, animals, and soil.

Spotted knapweed can turn open Michigan landscapes into a near-monoculture. It’s common along roads and disturbed ground, and once it dominates, native plants have a hard time getting back in.

Keeping it from seeding—and cleaning equipment after mowing—helps stop it from leapfrogging to new areas.

12. Purple Loosestrife

- Wetland choker: Replaces diverse native marsh plants with dense stands.

- Seed machine: Spreads efficiently through water and disturbed wet soil.

- Habitat downgrade: Looks pretty, but reduces the quality of food and shelter for wildlife.

Purple loosestrife is one of the trickiest Michigan invasives because people still mistake it for a “nice wildflower.” In wetlands and shoreline areas, it can take over fast and squeeze out the plant diversity that makes marsh habitat work.

Small patches can be pulled with care, but big infestations usually need an organized control effort so it doesn’t rebound.

13. European Frog-bit

- Floating mat-maker: Forms dense surface mats that block light.

- Oxygen and habitat impacts: Can change conditions for fish and native aquatic plants.

- Spreads on gear: Fragments and plant clusters can hitch rides between lakes.

European frog-bit looks harmless—little floating leaves, almost “cute.” But in Michigan waters, it can build thick mats that shade out native plants and reduce habitat quality in shallow areas.

Always check props, paddles, anchors, and trailers. Aquatic invasives don’t need much help to spread.

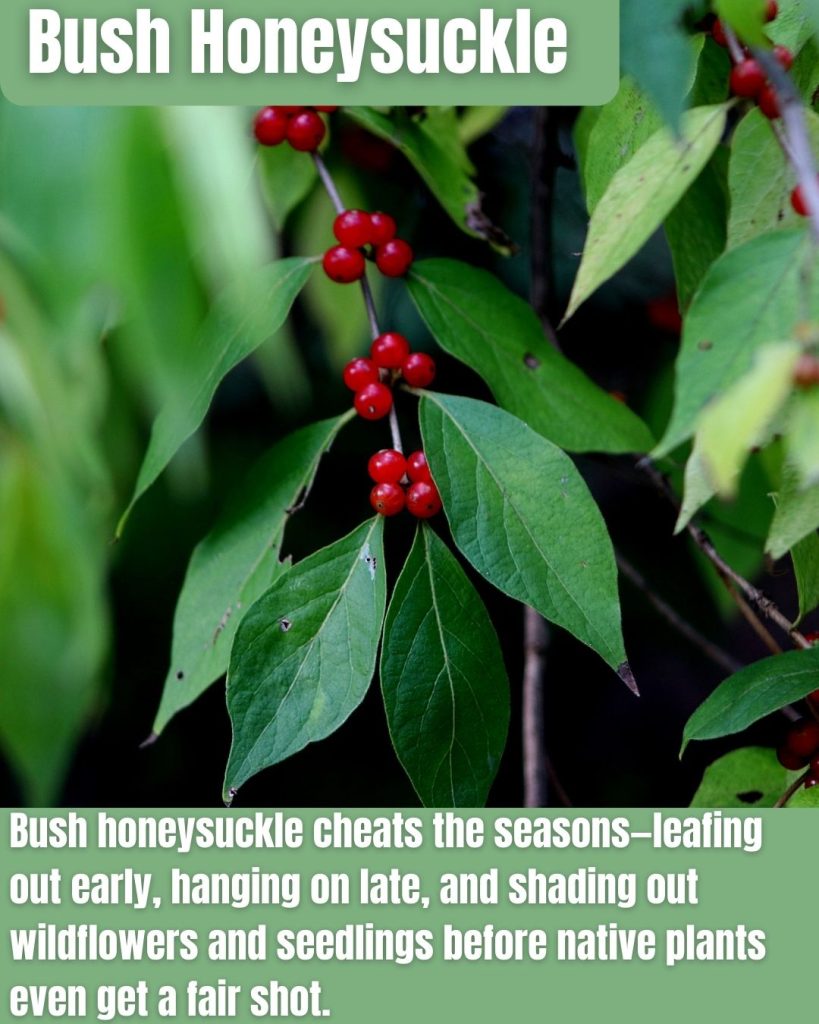

14. Bush Honeysuckle

- Understory takeover: Forms thick shrub layers that crowd out natives.

- Early leaf advantage: Leafs out early and holds leaves late, stealing light.

- Bird-spread berries: Seeds get carried into woods and along creek corridors.

In Michigan, invasive bush honeysuckles are the “quiet takeover” in many woodlots and parks. They create a dense shrub layer that blocks young trees and wildflowers from getting established.

Cutting and treating stumps is often the difference between “I removed it” and “it came back worse next year.”

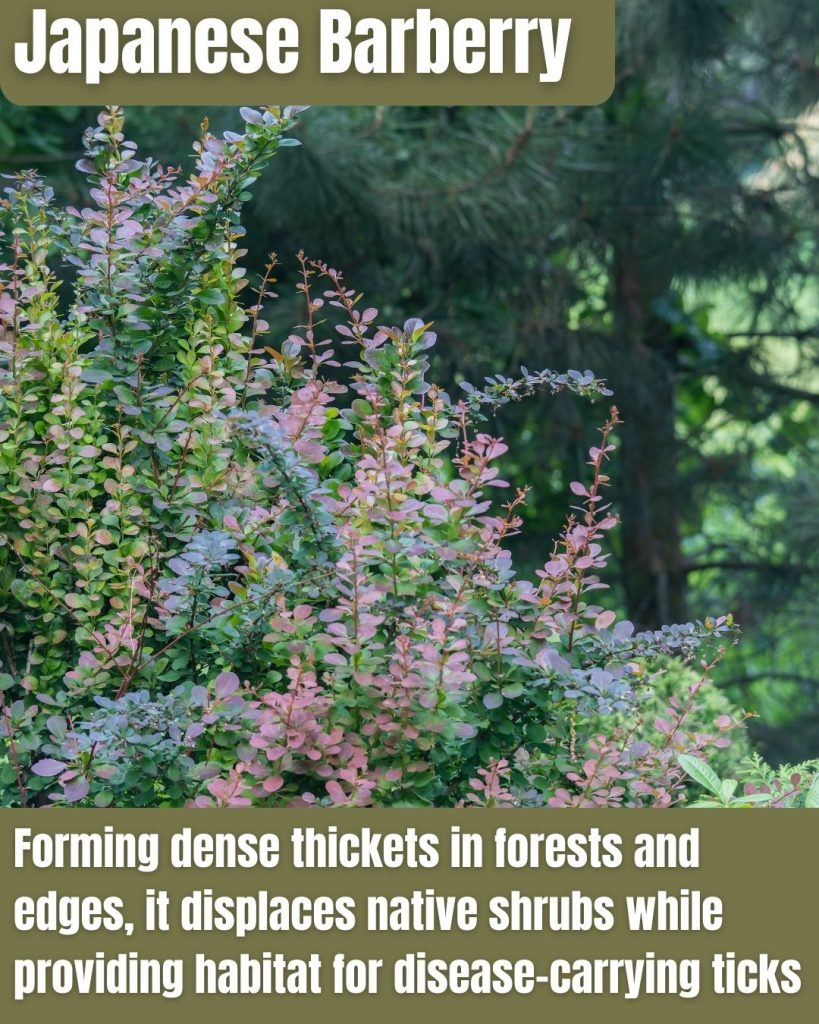

15. Japanese Barberry

- Spiny thickets: Creates dense, prickly patches that push out natives.

- Deer resistance: Often survives where native plants get browsed down.

- Yard escapee: Frequently spreads from landscaping into nearby woods.

Japanese barberry is a landscaping plant that doesn’t know when to stay put. In Michigan, it can form tight thickets in forest edges and understories, making it harder for native plants to compete.

Small plants can be dug out (roots and all). Bigger infestations usually take repeated work over multiple seasons.

16. Grass Carp

- Vegetation eater: Can remove large amounts of aquatic plants.

- Habitat shift: Less vegetation can mean less cover for young fish and wildlife.

- Human-linked spread: Stocking and accidental movement can create new problems.

Grass carp are often tied to “weed control,” but the bigger issue is that they can overshoot the goal. In the wrong place, too many carp can strip vegetation and change shallow-water habitat quickly.

Michigan water management decisions matter here—because once vegetation is gone, the whole system can shift.

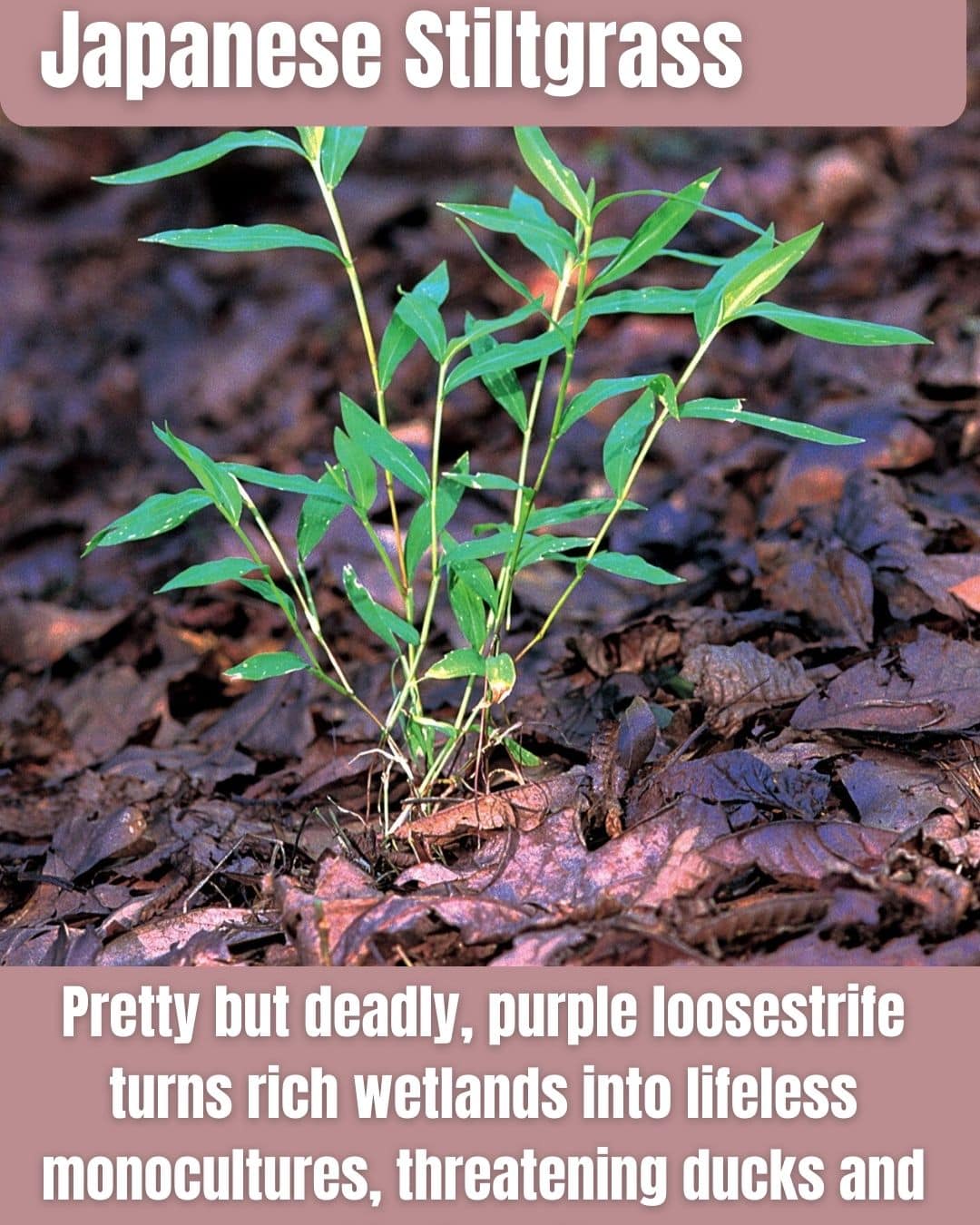

17. Japanese Stiltgrass

- Dense ground mats: Smothers native seedlings and wildflowers.

- Spreads on boots and pets: Tiny seeds hitch rides from trail to trail.

- Thrives in disturbance: Edges, flood zones, and logged areas are prime targets.

Japanese stiltgrass is one of those invasives that spreads quietly—until you realize a whole patch of forest floor is turning into a single-species carpet. Michigan trail corridors and disturbed woods can be especially vulnerable.

Mowing or cutting can work if timed before it seeds, but prevention—cleaning boots, gear, and mower decks—keeps it from hopping to new spots.

18. Water Chestnut

- Surface mat takeover: Can blanket shallow water and choke out natives.

- Recreation impacts: Makes paddling, fishing, and swimming miserable in infested areas.

- Spiny seeds: Hard, sharp nuts can be a hazard in shallow water.

Water chestnut is built to dominate shallow water. When it takes hold, it can create thick floating mats that block sunlight and turn good habitat into a stagnant mess.

Any plant stuck to trailers or tangled in props should be removed before you leave the launch—every time.

19. White Perch

- Competes with natives: Can pressure native fish by competing for food and space.

- Flexible survivor: Tolerates a range of water conditions.

- Spreads through movement: Illegal stocking and bait release are common pathways.

White perch can blend into the background until you see what it does to a fish community over time. It’s adaptable, it reproduces, and it can slowly reshape what anglers catch in connected Michigan waters.

Never release baitfish, and never move fish between lakes “just to see what happens.” That’s how invasions start.

20. Rusty Crayfish

- Shreds habitat: Can reduce aquatic plants and disturb shoreline cover.

- Outcompetes natives: Pushes out Michigan’s native crayfish species.

- Bait bucket risk: Often spreads when people dump live bait.

Rusty crayfish are like tiny, armored bulldozers. In Michigan lakes and streams, they can chew through aquatic vegetation and muscle out native crayfish, changing the shallow-water habitat fish rely on.

This one comes back to the same rule again: don’t dump live bait. Ever.

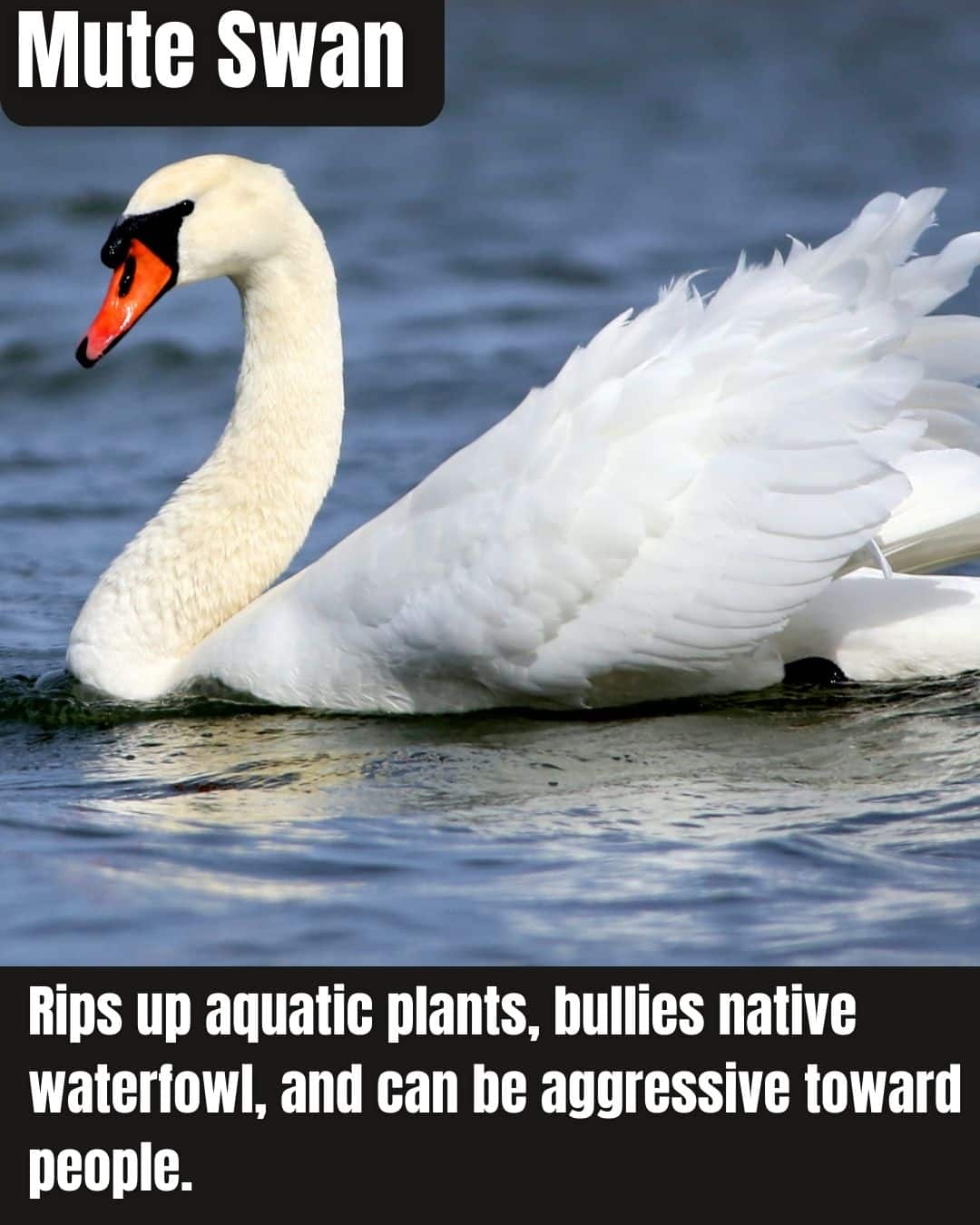

21. Mute Swan

- Plant demolisher: Eats and uproots aquatic vegetation needed by fish and native waterfowl.

- Territorial brawler: Chases off native birds and can get aggressive near nests.

- Big footprint: Large birds with large impacts—especially in shallow bays and wetlands.

Mute swans are beautiful—no argument there. But in Michigan waters, they can behave like an ecological wrecking ball: uprooting plants, pushing out native birds, and creating conflict with people when they defend nests.

If you’re around swans with kids or dogs, give them space. A protective swan can move faster than you think.

22. Giant Hogweed

- Skin hazard: Sap can cause severe skin reactions when exposed to sunlight.

- Large, fast-growing: Can tower over people and shade out native plants.

- Do not handle: Cutting or pulling without proper protection is risky.

Giant hogweed is one of the few invasives that’s not just “bad for habitat.” It can be dangerous to people. The sap can trigger painful skin reactions, especially when sunlight hits the area afterward.

If you suspect hogweed, the safest move is to avoid contact and report it through local or state invasive reporting channels so it can be handled properly.

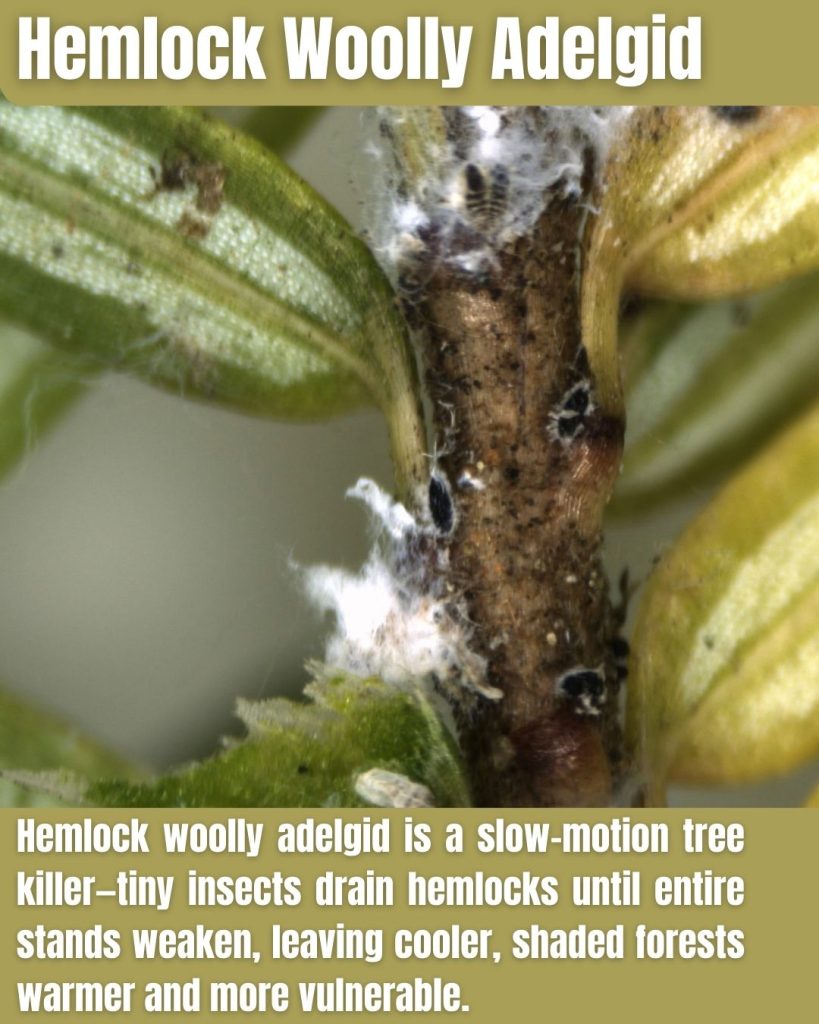

23. Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

- Hemlock killer: Weakens trees by feeding on sap, leading to decline.

- “Cottony” clue: White woolly masses on twigs are a common sign.

- High-value trees: Hemlocks shape cool, shaded forest habitat—losing them changes everything.

Hemlocks create a very specific Michigan forest feel—cooler shade, steady moisture, and shelter for wildlife. Hemlock woolly adelgid threatens that by slowly draining the tree until it can’t keep up.

Early detection is a big deal. If you see the cottony clusters on hemlock twigs, it’s worth reporting so professionals can confirm and respond.

24. Spotted Lanternfly

- Hitchhiker pest: Eggs can travel on vehicles, trailers, and outdoor gear.

- Plant stress: Feeding can weaken plants and promote sooty mold.

- “See it, report it” insect: Early reporting helps slow spread.

The spotted lanternfly is one of those invasives that spreads because it’s good at riding with people. Egg masses can end up on almost anything—especially things that sit outside, then travel.

If Michigan residents spot it, the smart play is to document it and report it through the recommended state/local channels. With invasives like this, early action is the whole game.

25. Red Swamp Crayfish

- Wetland and ditch invader: Can tolerate tough conditions and spread quickly.

- Competes and disrupts: Can pressure native species and disturb habitat.

- Human-assisted spread: Aquaria, bait use, and releases are common pathways.

Red swamp crayfish are tough, fast to reproduce, and good at surviving where other species struggle. That makes them a strong invader when they get introduced outside their native range.

This one circles back to the big prevention rule for Michigan waters: don’t release aquarium animals, don’t dump bait, and don’t move live critters between lakes and streams.