Tired of seeing your garden overtaken by aggressive invaders that outcompete native plants and harm wildlife?

These 25 invasive plant species have wreaked havoc across the United States, displacing beneficial flora and altering ecosystems.

Learn where each comes from, how it arrived, where it thrives, and effective control methods to protect your landscape.

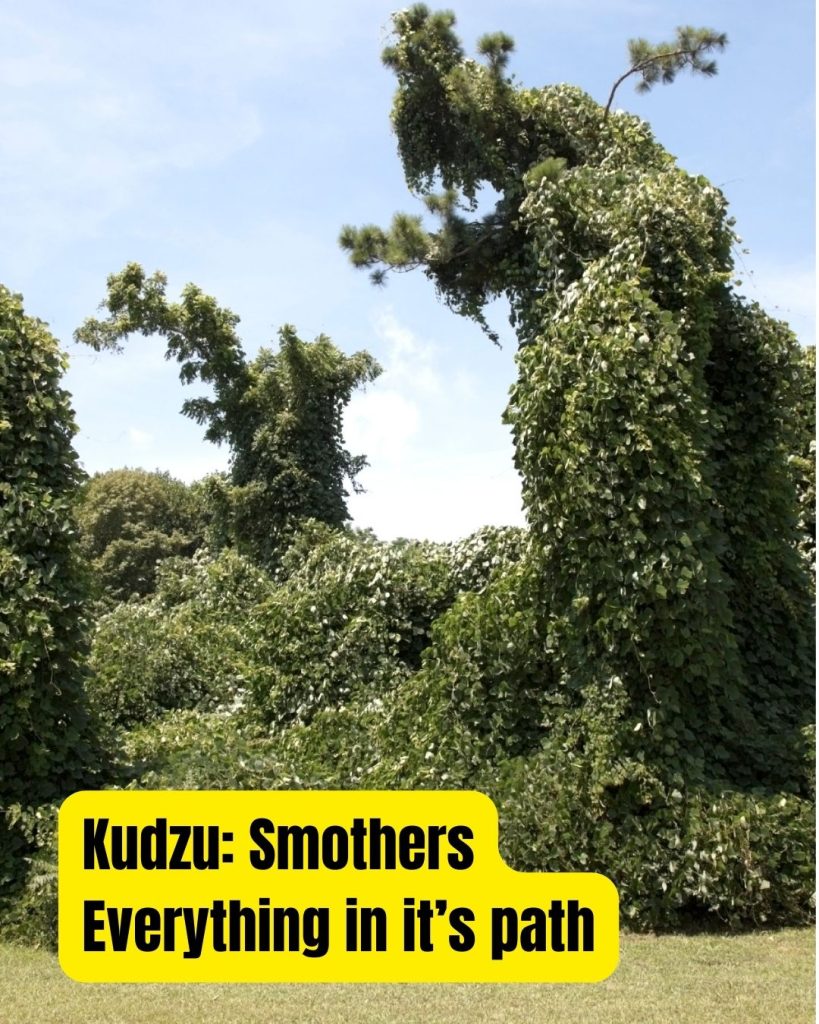

1. Kudzu (Pueraria Montana var. lobata)

Kudzu is a fast‑growing vine native to Southeast Asia, introduced in the 1800s for ornamental use and soil stabilization.

It now blankets millions of acres across the Southeast, smothering trees, shrubs, and native groundcover under thick mats.

Persistence is key to control: mow or graze repeatedly, apply systemic herbicides like glyphosate, and establish competitive native shrubs to starve out resprouts.

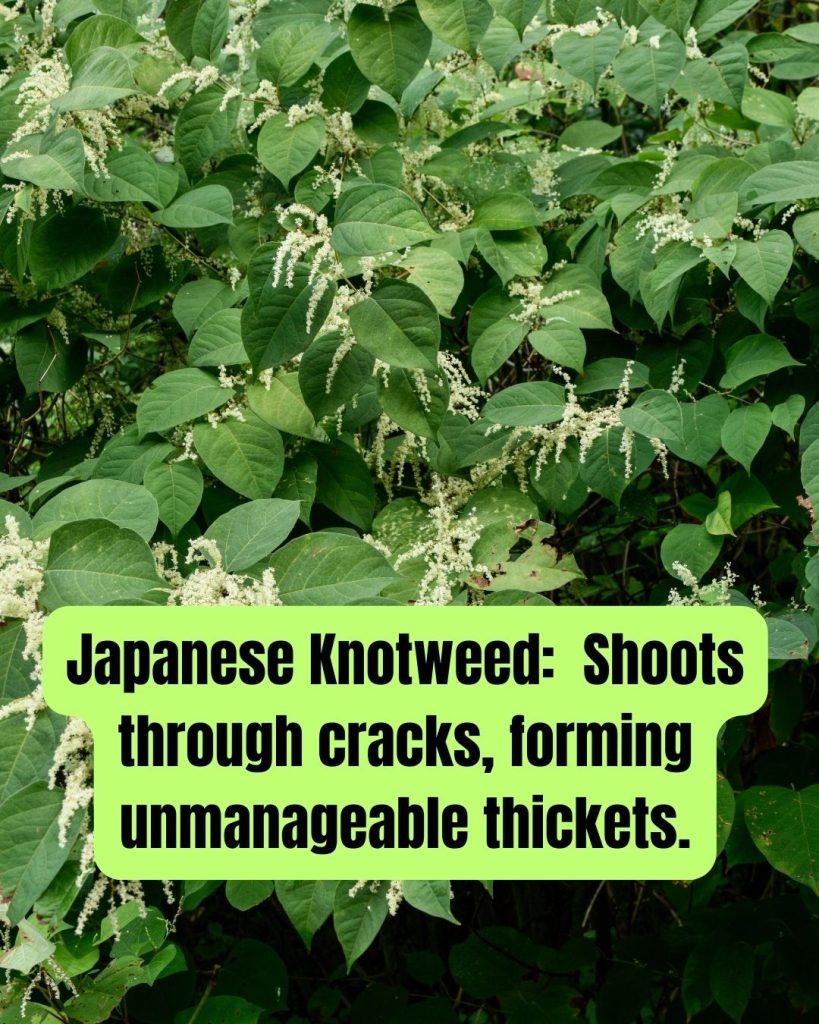

2. Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica)

Originally from East Asia, Japanese knotweed arrived in the 1800s as a showy garden plant.

It escaped cultivation along waterways, roadsides, and disturbed soils from New England to the Pacific Northwest, forming impenetrable thickets.

Eradication takes patience: dig or cut rhizomes deeply, apply systemic herbicides over multiple seasons, and ensure all fragments are removed or bagged to prevent regrowth.

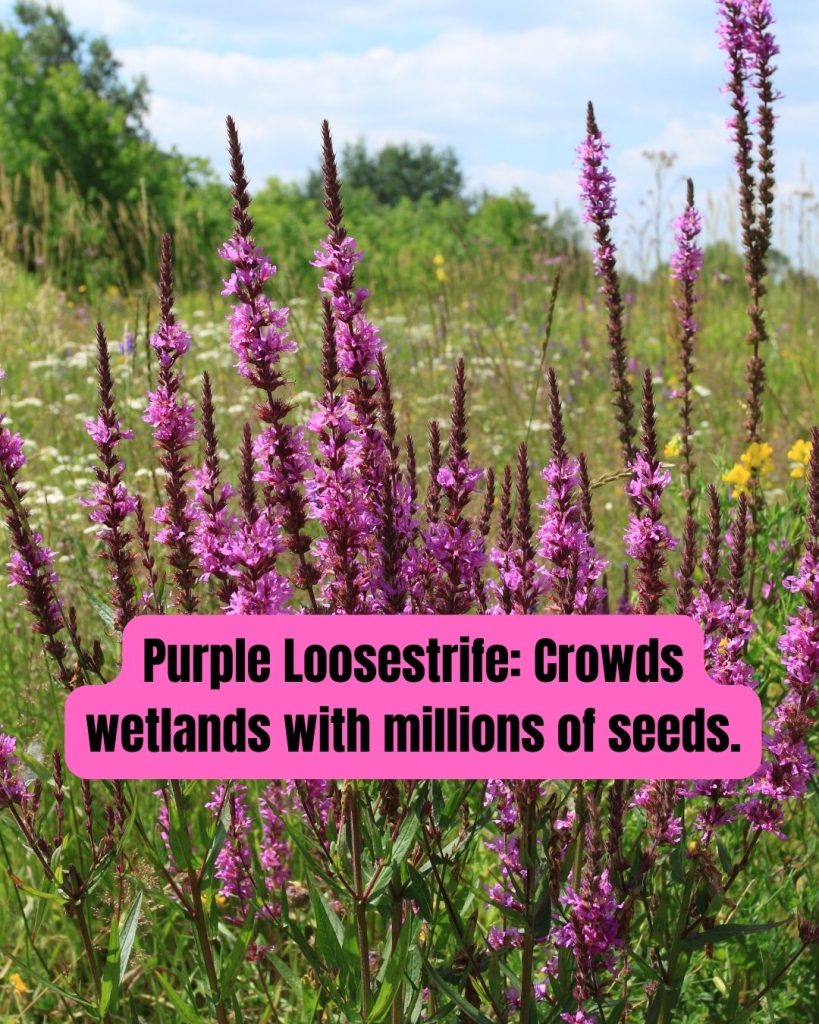

3. Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

Native to Europe and Asia, purple loosestrife hitched a ride in ship ballast and wool imports in the 1800s.

It now carpets wetlands, riverbanks, and ditches from the Atlantic Coast to the Midwest, choking out native marsh plants.

Combine tactics for best results: pull young plants by hand, use water‑safe glyphosate for larger stands, and release leaf‑eating beetles as biocontrol agents.

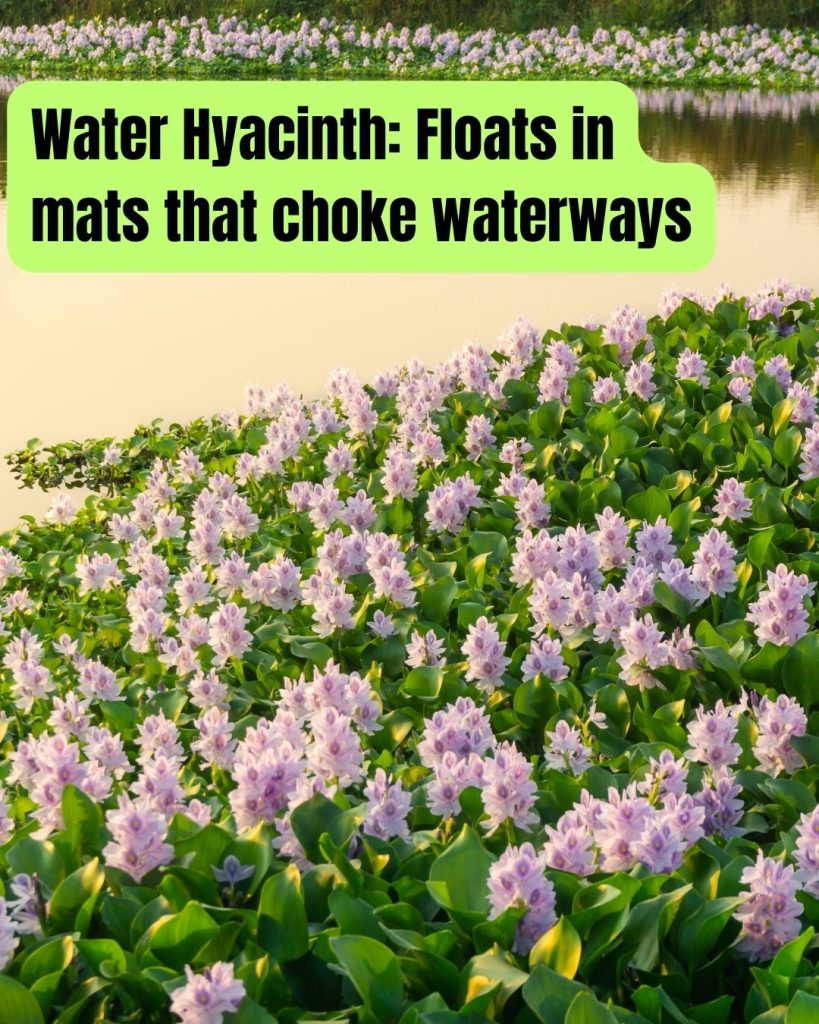

4. Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes)

This floating beauty from the Amazon Basin was introduced as a pond plant in the late 1800s.

It now clogs lakes, rivers, and canals across the South and Gulf Coast, forming mats that block sunlight and deplete oxygen.

Mechanical removal plus biology: harvest mats, apply 2,4‑D herbicide carefully, and introduce weevils that feed on the plant for long‑term suppression.

5. Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata)

Hydrilla, native to Asia, Africa, and Australia, arrived in Florida in the 1950s via aquarium releases.

It now thrives in warm lakes and slow rivers nationwide, forming dense underwater forests.

Control options include: benthic barriers to block growth, targeted herbicide treatments, and mechanical harvesting before it flowers and spreads fragments.

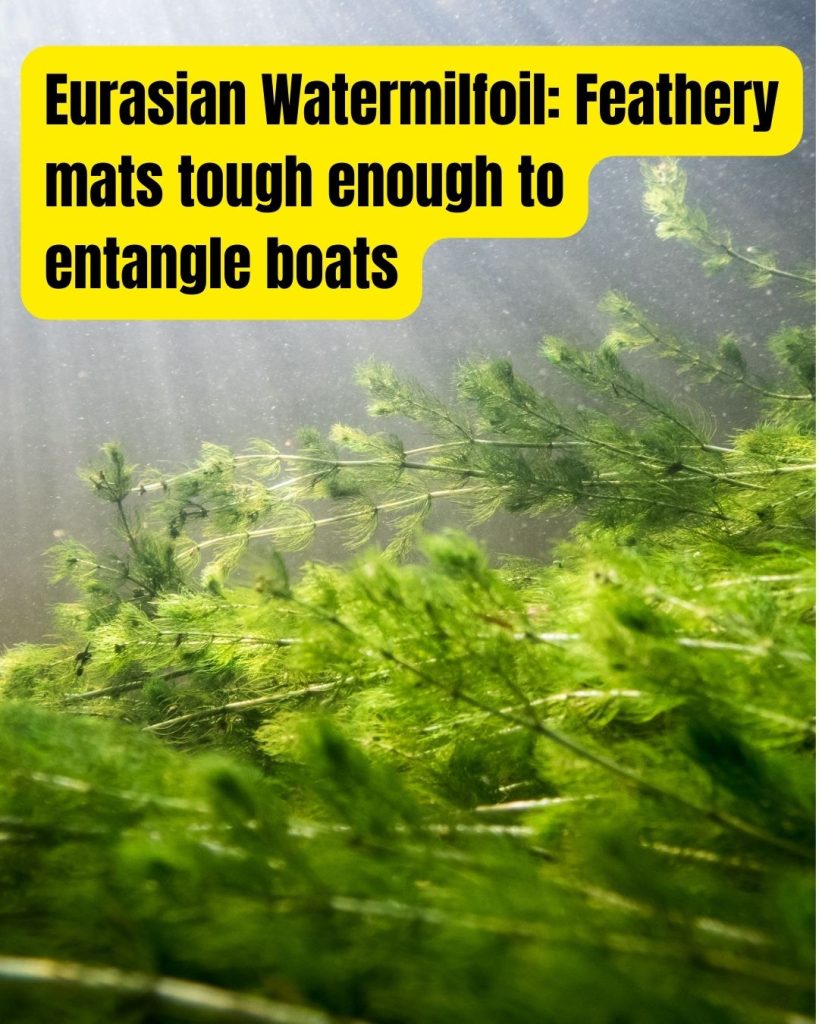

6. Eurasian Watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum)

Brought over in ship ballast early in the 20th century,

Eurasian watermilfoil invades lakes and ponds from coast to coast. Its feathery leaves form thick mats that entangle boat motors and crowd out natives.

Fight it by: installing bottom barriers, spot‑treating with approved aquatic herbicides, and hand‑pulling or harvesting before seed production.

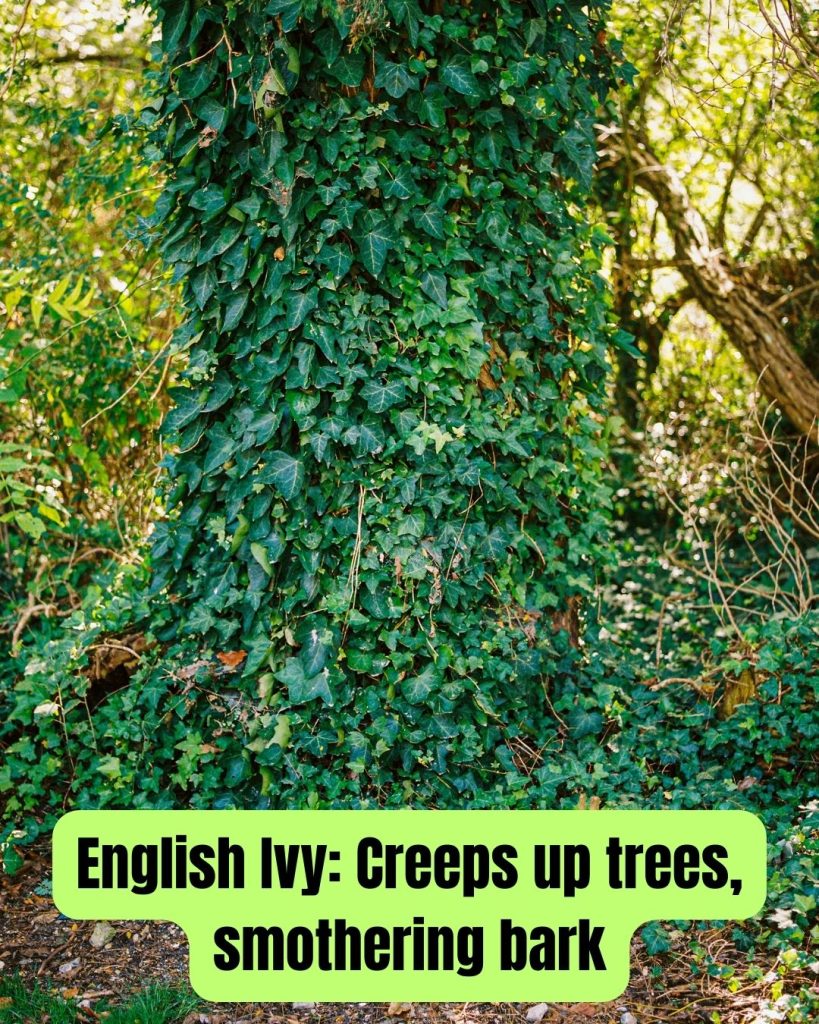

7. English Ivy (Hedera helix)

Hailing from Europe, English ivy was planted as groundcover and ornamental in the 1800s.

It now climbs trees and fences throughout the U.S., shading out understory plants and eventually killing host trees.

Keep it at bay by: cutting vines at the base, removing all root fragments, and replacing with native groundcovers like wild ginger or foamflower.

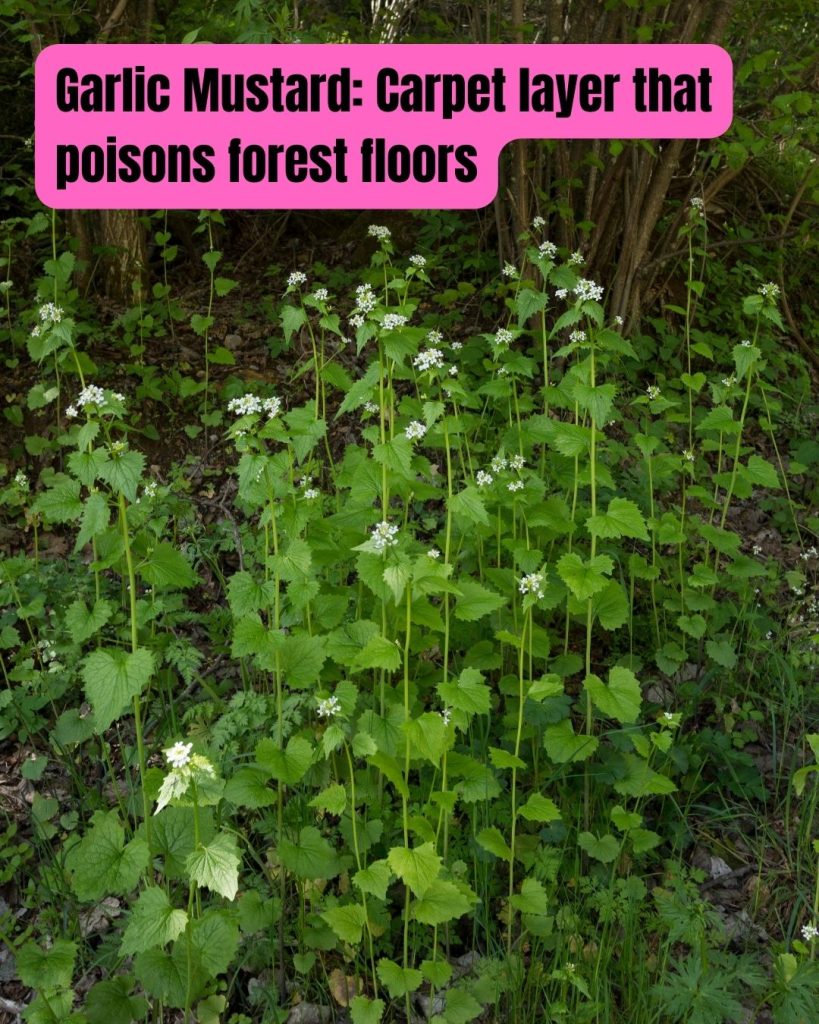

8. Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Native to Europe, garlic mustard snuck in as a culinary herb in the 1860s.

It now carpets woodlands and forest edges across 30+ states, releasing chemicals that hinder native wildflowers.

Early spring hand‑pulling before seed set works well, followed by several seasons of monitoring and removing rosettes to exhaust root reserves.

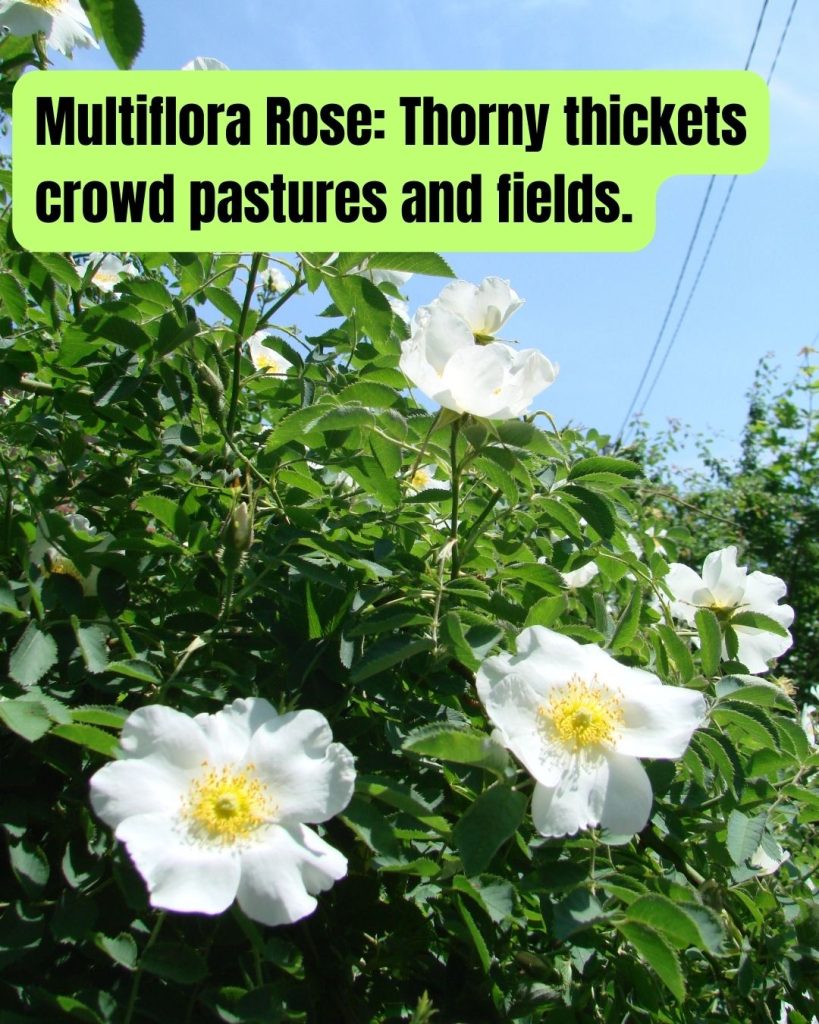

9. Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora)

Introduced from Asia in the late 1800s as a living fence and soil stabilizer, multiflora rose now forms impenetrable thickets in pastures, roadsides, and forests.

Its arching canes crowd out native shrubs and grasses.

Control by: repeated cutting or mowing, herbicide stem injections, and revegetation with native shrubs once cleared.

10. Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata)

This nitrogen‑fixing shrub from Asia was planted for wildlife cover and erosion control in the 1950s.

It now invades grasslands and forest edges across much of the U.S., altering soil fertility.

Cut‑and‑paint treatment on cut stumps with glyphosate or triclopyr prevents resprouting and allows native plants to reclaim the site.

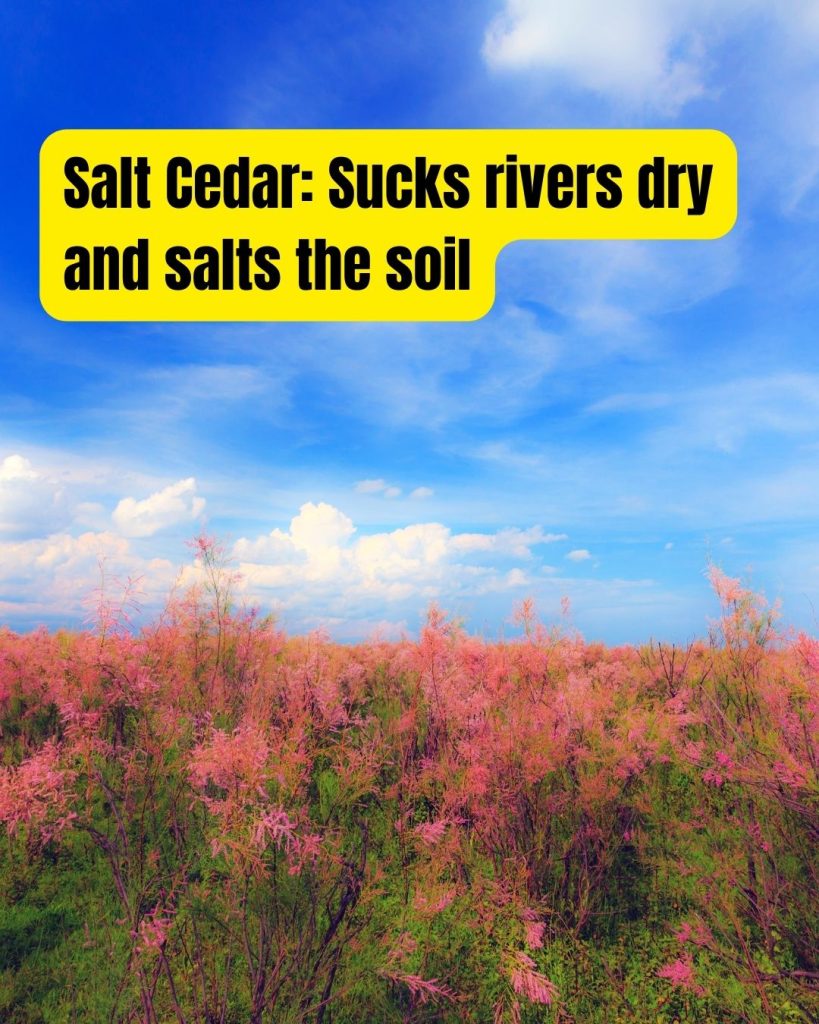

11. Salt Cedar (Tamarix ramosissima)

Salt cedar, native to Eurasia and Africa, was introduced in the early 1800s for erosion control.

It now invades arid riverbanks and floodplains in the West, consuming large water volumes and increasing soil salinity.

Mechanical removal plus herbicide on stumps, alongside planting of native cottonwoods and willows, restores riparian habitats best.

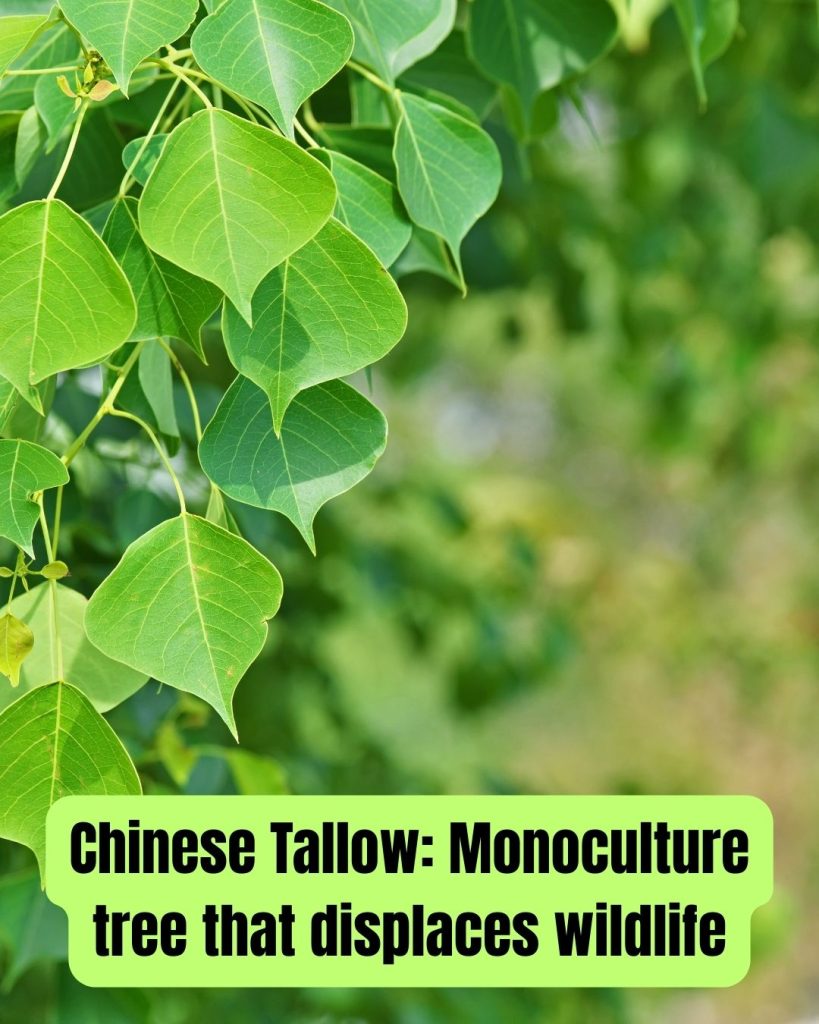

12. Chinese Tallow (Triadica sebifera)

Originally from China and Japan, Chinese tallow was imported in the 1700s for its waxy oil.

It now dominates wetlands and uplands in the Southeast, forming monocultures that offer little wildlife value.

Combine hand‑pulling of seedlings with basal bark or cut‑stem herbicide applications for established trees to reduce populations.

13. Tree‑of‑Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

Native to China and Taiwan, tree‑of‑heaven arrived in the late 1700s as an ornamental.

It now colonizes vacant lots, roadsides, and forest edges nationwide, releasing growth‑inhibiting chemicals.

Girdle or cut stems and immediately apply herbicide to the cut surface; follow up on vigorous suckers that sprout from roots.

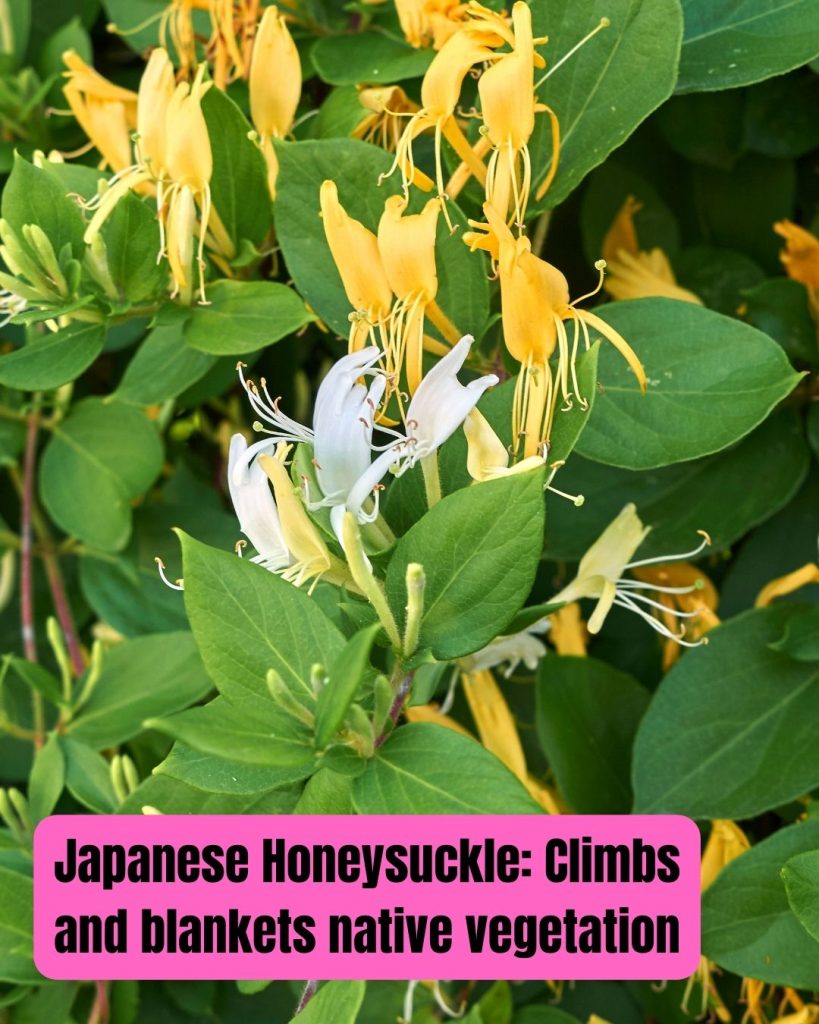

14. Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)

This vine from Japan and Korea was introduced in the 1800s as an ornamental and erosion control plant.

It now carpets forest floors and climbs trees across the eastern U.S., outcompeting native vines.

Pull vines by hand, ensuring root removal, or apply glyphosate to cut stems in late summer when plants translocate chemicals to roots.

15. Bush Honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.)

Several species of bush honeysuckles from Asia arrived as landscape shrubs in the early 1900s.

They now form dense thickets in woodlands and fields, shading out native wildflowers.

Cut‑and‑dab herbicide treatments on stumps, combined with hand‑pulling young shoots, helps deplete the rootstocks over time.

16. Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus)

Introduced from Asia in the 1800s as an ornamental twining vine, oriental bittersweet now strangles trees and shrubs along forest edges in 30+ states.

Lop and remove vines, cut trunks near the base and paint with herbicide, then monitor for seedlings and resprouts.

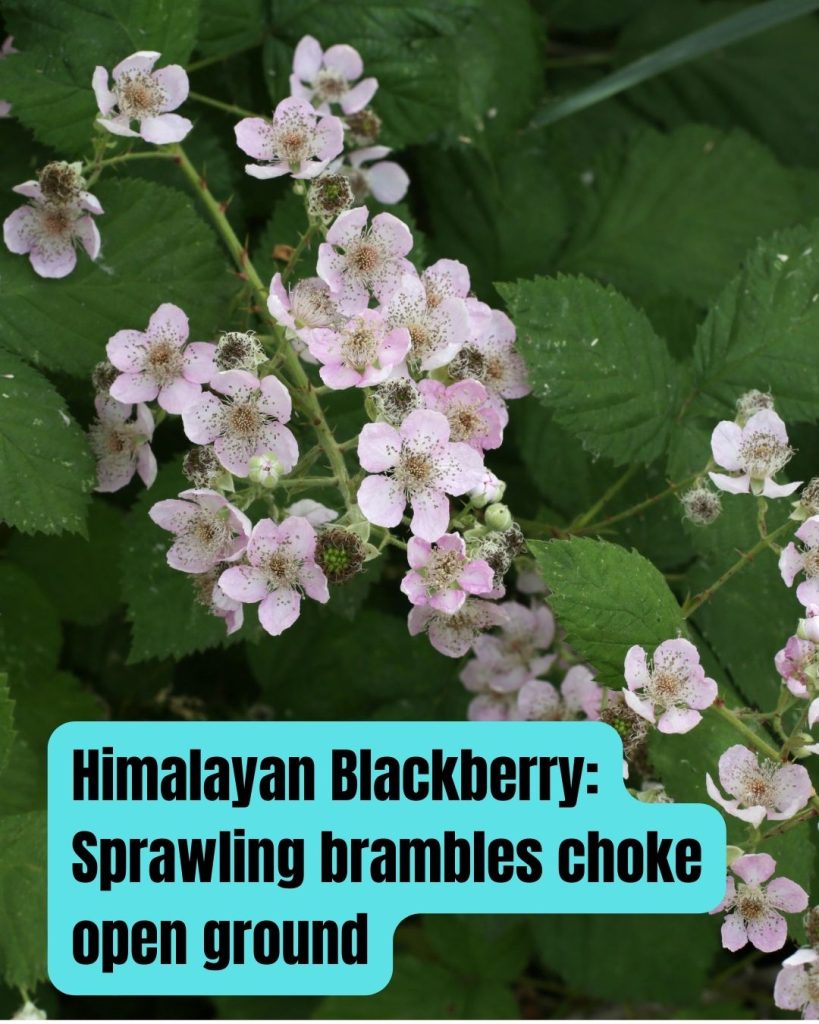

17. Himalayan Blackberry (Rubus armeniacus)

Brought from Europe and North Africa in the late 1800s for fruit production, Himalayan blackberry now sprawls across roadsides, pastures, and riparian zones in the Pacific Northwest.

Mow or cut canes repeatedly to weaken plants, or apply glyphosate during active leaf growth, and plant native shrubs to reclaim cleared areas.

18. Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense)

Accidentally introduced from Europe in the 1600s as a seed contaminant, Canada thistle now infests croplands, pastures, and roadsides nationwide.

It spreads via creeping roots and abundant wind‑blown seeds.

Repeated mowing or tillage before seed set, combined with spot herbicide treatments, depletes root reserves over several seasons.

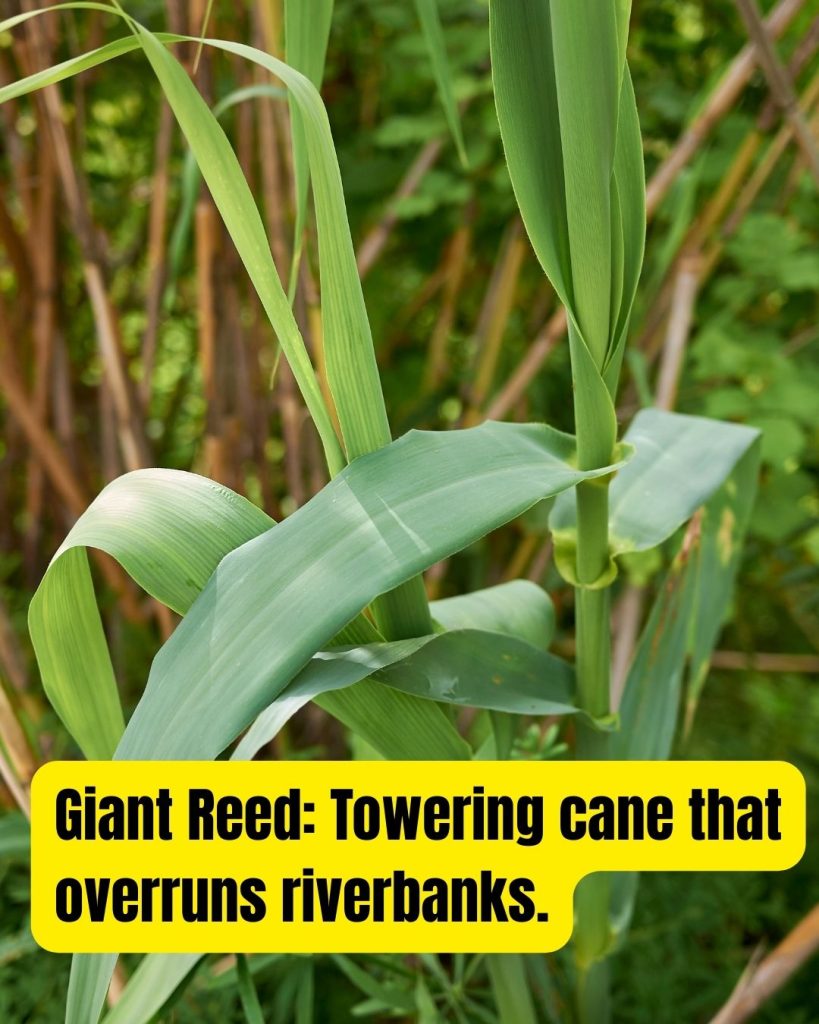

19. Giant Reed (Arundo donax)

Native to the Mediterranean, giant reed was planted for windbreaks and erosion control in the early 1900s.

It now forms dense stands along waterways in California and the Gulf Coast, outcompeting native marsh plants.

Cut stems near the base and apply aquatic‑approved herbicide, then replant with native sedges and rushes to prevent reinvasion.

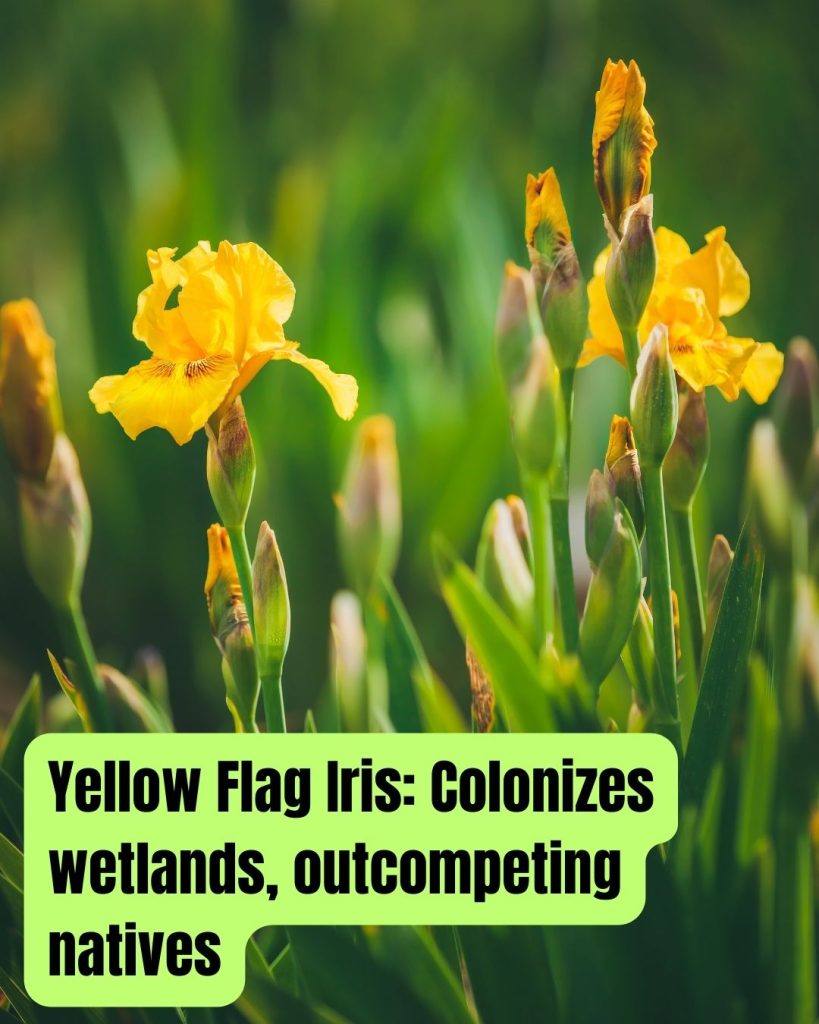

20. Yellow Flag Iris (Iris pseudacorus)

This showy iris from Europe was introduced in the 1800s for water gardens.

It now escapes into wetlands and slow streams in the North and Midwest, forming dense colonies that crowd out native marsh species.

Hand‑dig rhizomes and remove all fragments, or apply glyphosate to foliage in late summer when translocation to roots is highest.

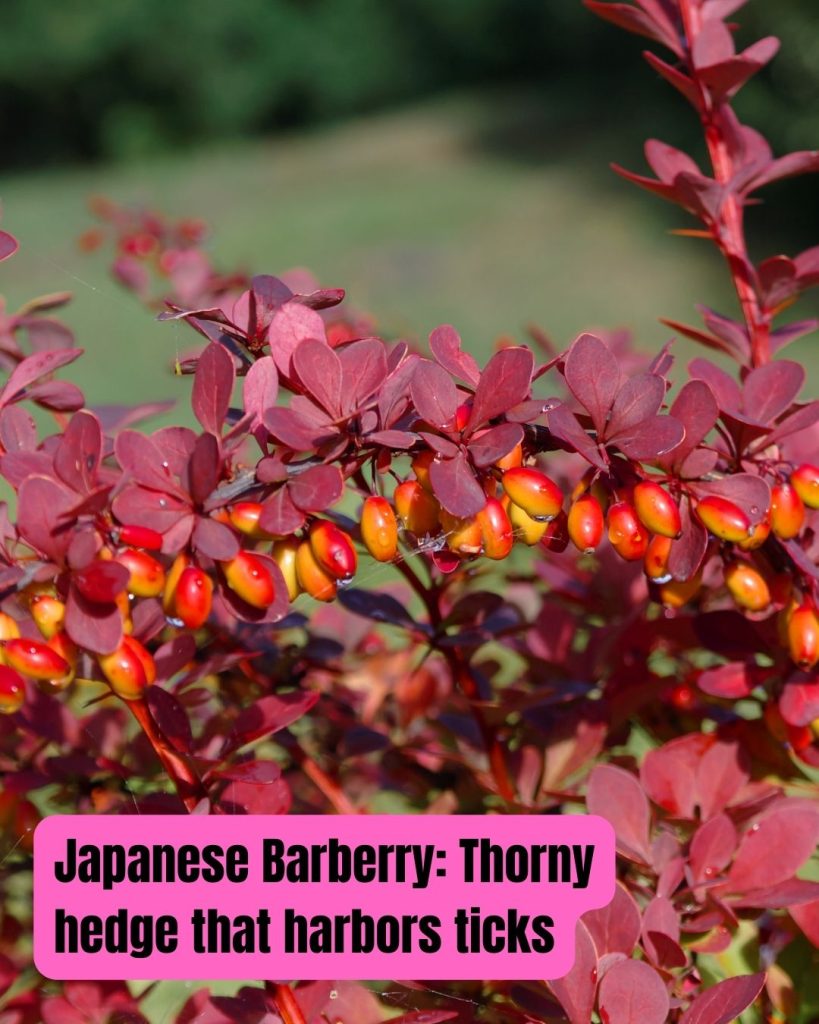

21. Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

Native to Japan, barberry was brought over in the late 1800s as an ornamental hedge plant.

It now dominates forest understories in the Northeast and Midwest, increasing ticks and shading out wildflowers.

Cut stems and treat stumps with herbicide, or use stem injections, and reseed with native groundcovers afterward.

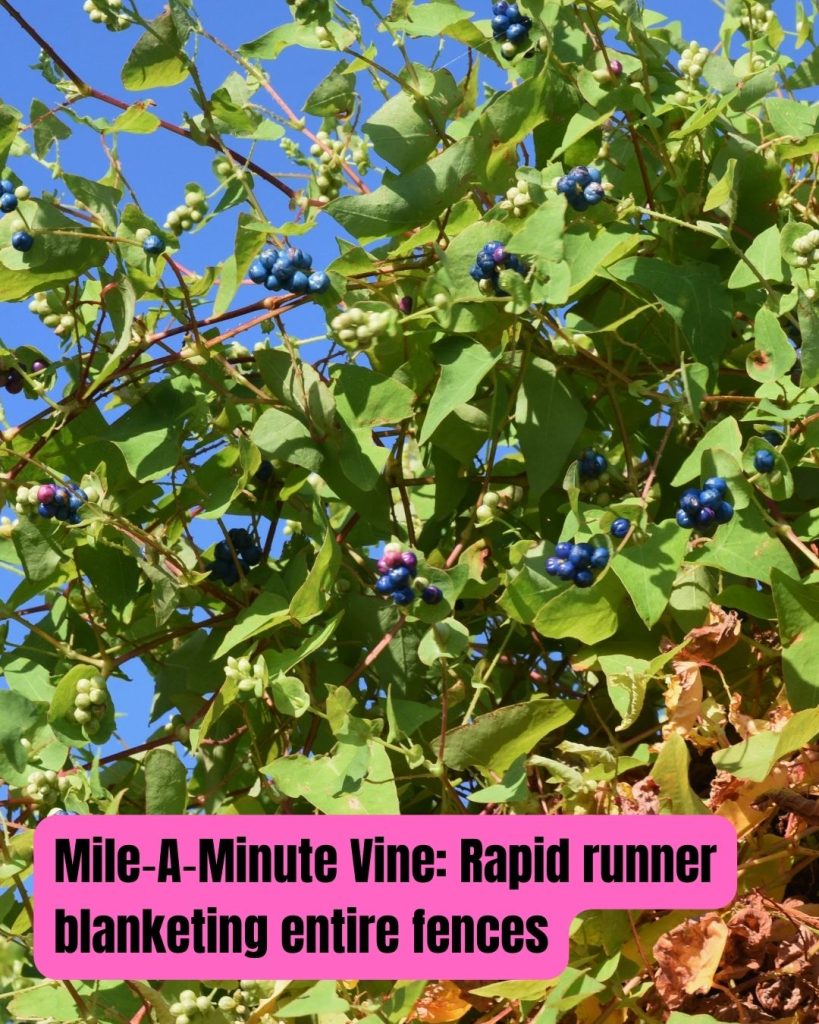

22. Mile‑A‑Minute Vine (Persicaria perfoliata)

This fast‑climbing vine from Asia arrived in the 1930s as a packing material.

It now blankets forests, fields, and roadsides in the Mid‑Atlantic and Northeast.

Hand‑pull young plants before fruiting, bag all material, and apply herbicide to larger patches in early summer.

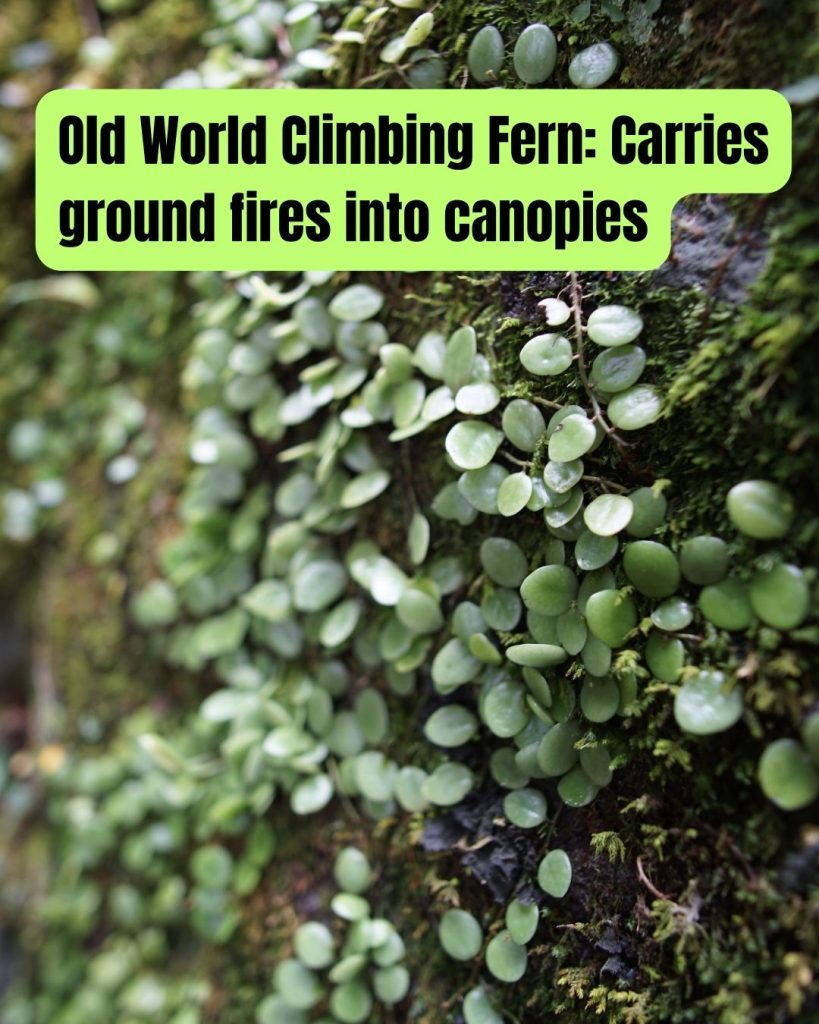

23. Old World Climbing Fern (Lygodium microphyllum)

Brought from Africa and Asia for ornamental use, the Old World climbing fern now smothers swamps and hammocks in South Florida.

It climbs into tree canopies and increases fire risk by carrying ground fires upward.

Spray foliage with glyphosate or metsulfuron‑methyl, and cut heavy vines before treatment to improve herbicide contact.

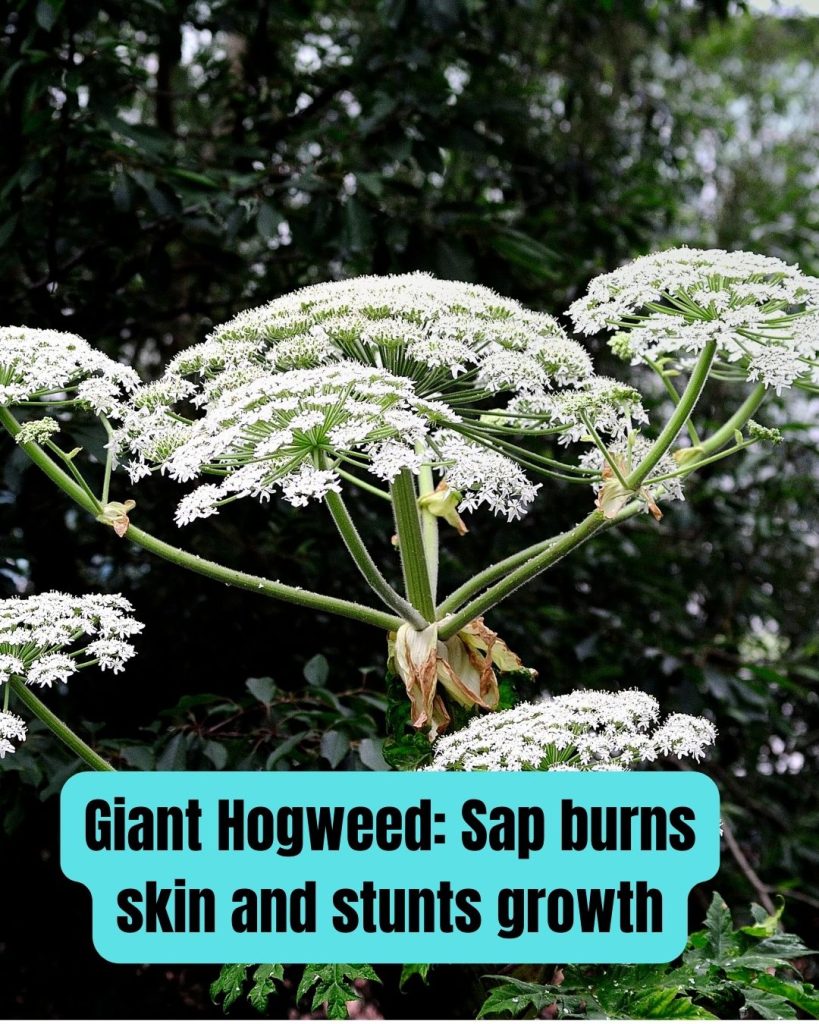

24. Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)

Native to the Caucasus, giant hogweed was planted in botanical gardens in the early 1900s.

It now invades roadsides, riverbanks, and forest edges in the Northeast and Pacific Northwest.

Wear protective gear, cut flowering stalks before seed set, and apply systemic herbicide to crowns to prevent painful blisters from its sap.

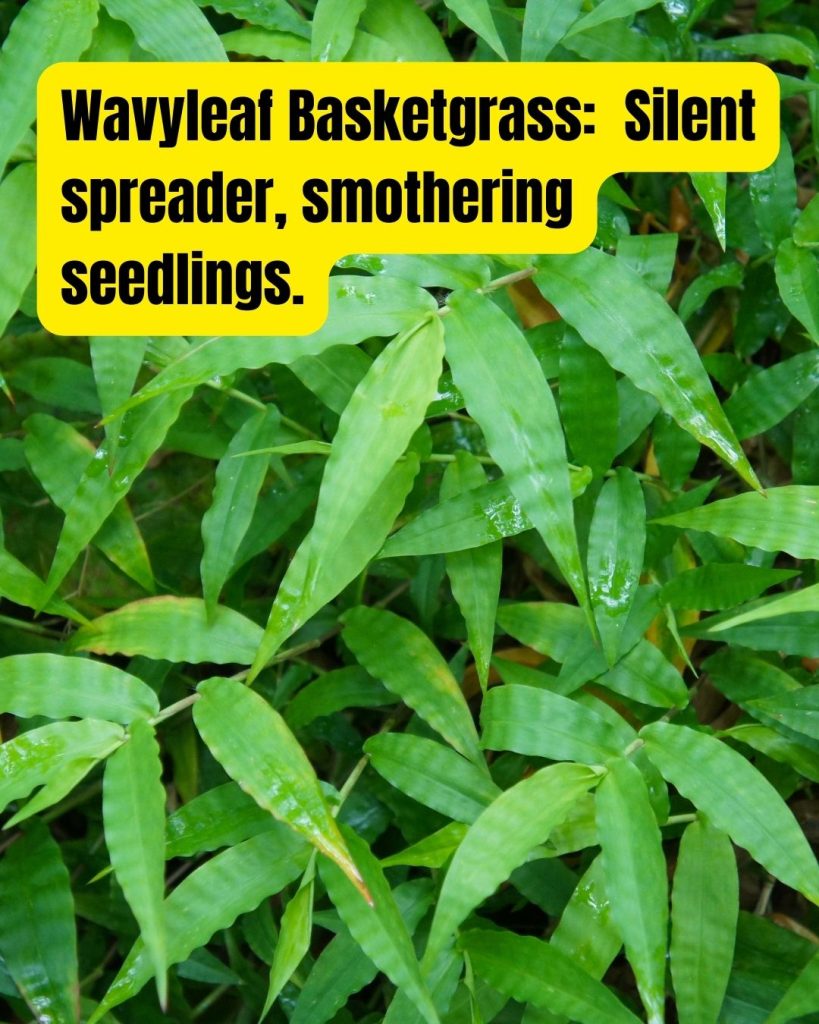

This shade‑tolerant grass from Asia was first detected in the Mid‑Atlantic in 1996. It now carpets forest floors in patches across several Eastern states, crowding out seedlings and native groundcovers.

Hand‑pull or hoe small infestations, bag and dispose of plant material, and monitor annually to catch new outbreaks early.

Bonus: 5 Common Questions About Invasive Plant Species

What makes a plant “invasive”?

An invasive plant is non‑native and establishes, spreads rapidly, and causes harm to ecosystems, economies, or human health.

How can I stop invasives from spreading?

Clean gear, boots, and equipment before moving between sites, and never dump garden waste in natural areas.

When is the best time to control them?

Target invasives before seed set in spring or early summer, when removal yields the greatest impact.

Should I tackle large infestations myself?

Small patches can often be managed DIY, but hire professionals for dense or sensitive habitats to ensure safe, effective eradication.

Where do I report new sightings?

Contact your state’s invasive species hotline or local USDA office—early detection is key to protecting native ecosystems.