Hey there, nature lovers and curious Californians! Imagine strolling through our stunning golden hills, pristine beaches, or lush forests, only to realize that some sneaky outsiders are crashing the party.

These invasive species aren’t just uninvited guests—they’re ecosystem bullies, outcompeting natives, spreading diseases, and costing us billions in damage.

From tenacious plants choking waterways to crafty critters devouring local wildlife, California’s biodiversity is at risk. Buckle up as we explore the top 25 invaders you need to know.

1. Yellow Starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis)

- This prickly plant can produce up to 150,000 seeds per square yard, turning fields into spiky minefields!

- Its flowers resemble cheerful yellow suns, but they’re toxic to horses, causing a fatal condition known as “chewing disease.”

- Bees love its nectar, but it ironically reduces overall biodiversity by dominating landscapes.

Yellow starthistle hails from the Mediterranean region and Eurasia, accidentally introduced to California in the mid-1800s via contaminated alfalfa seeds brought for farming.

Once here, it exploded across rangelands, outcompeting native grasses and forbs.

This reduces forage for livestock and wildlife, increases wildfire risk, and costs millions in control efforts, threatening California’s agricultural economy and natural habitats.

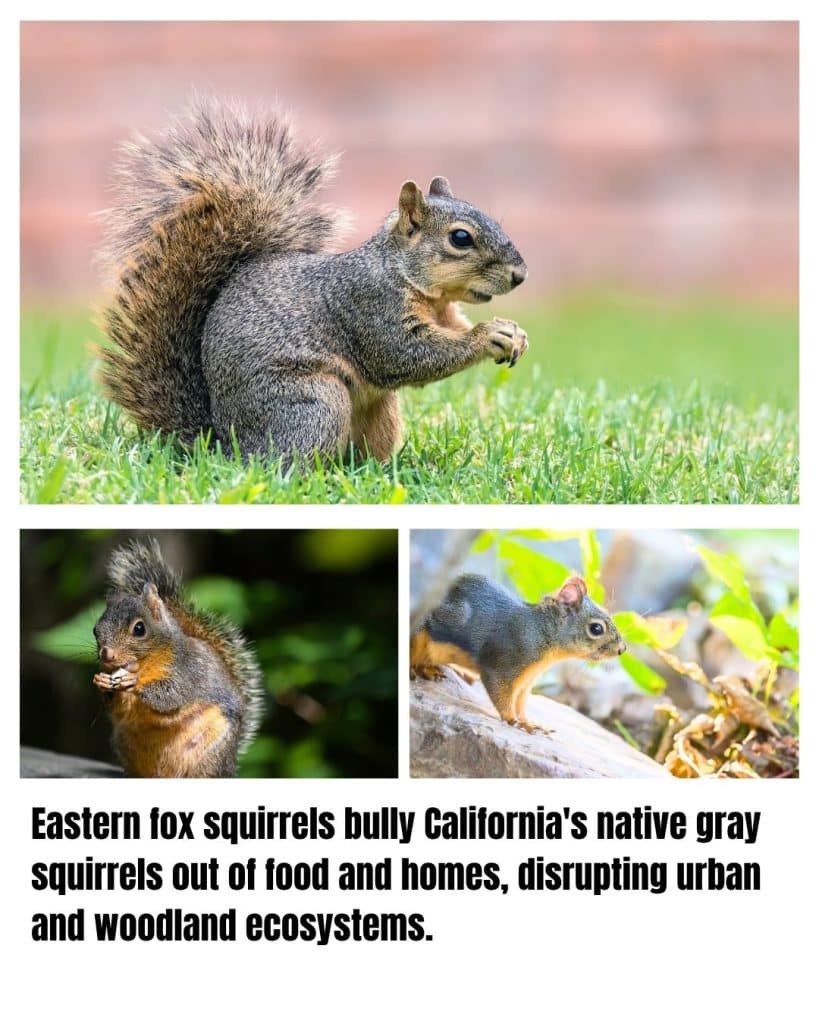

Eastern Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger)

- These squirrels can leap 15 feet between trees—acrobatic pros!

- They bury nuts but forget many, accidentally planting trees.

- Their tails act as sunshades and blankets.

Native to the eastern U.S., they were introduced to California in the 1870s for hunting and aesthetics.

They outcompete native western gray squirrels for food and habitat, spreading into urban and forest areas.

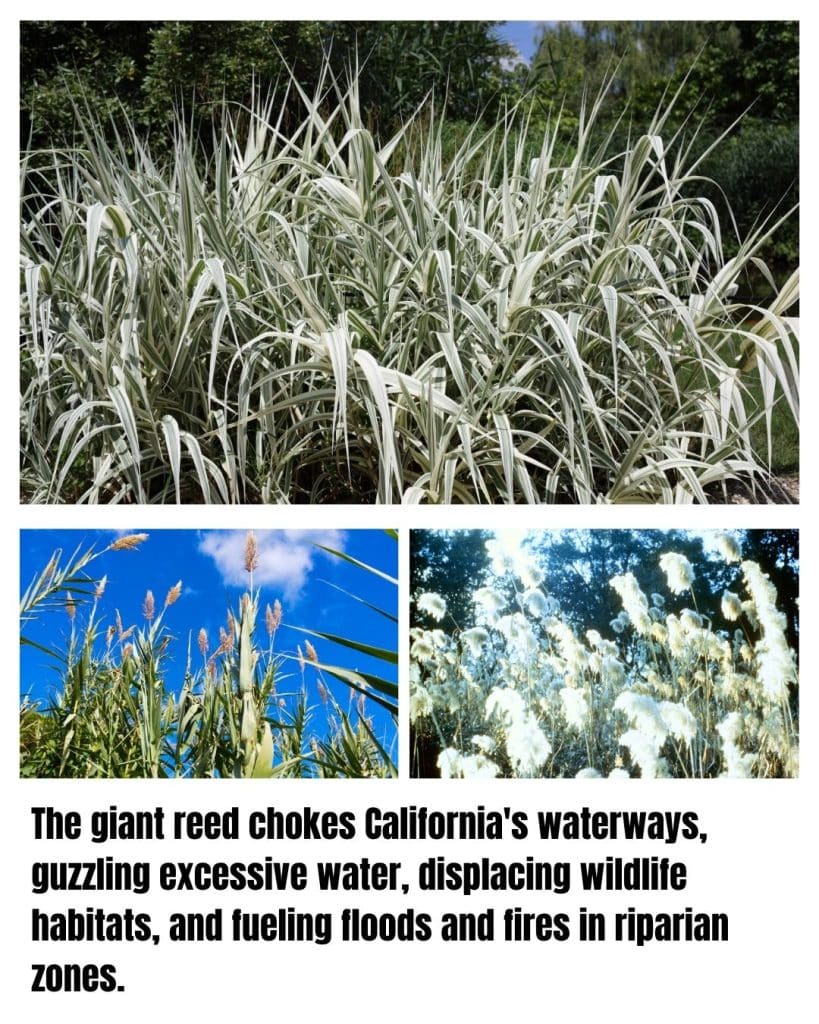

Giant Reed (Arundo donax)

- This towering grass can grow up to 30 feet tall, like a natural skyscraper in wetlands!

- It’s been used historically for making musical instruments, like clarinet reeds.

- Despite its size, it spreads rapidly through underground rhizomes, forming dense stands overnight.

Native to the Mediterranean and parts of Asia, giant reed was introduced to California in the 1800s for erosion control and ornamental purposes.

In California, it invades riparian areas, sucking up massive amounts of water (up to 20% more than natives) and altering river flows.

This increases flood risks, promotes wildfires due to its flammability, and displaces habitat for endangered species like the least Bell’s vireo.

European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

- They mimic sounds, including car alarms and human speech—feathered impressionists!

- Flocks can number in the millions, creating “black sun” murmurations.

- Introduced by Shakespeare fans wanting all his birds in America.

From Europe, a group was released in New York in 1890 and spread to California.

They compete with native cavity-nesters for holes, reducing populations of birds like bluebirds.

Crop damage and aircraft hazards add to their impact.

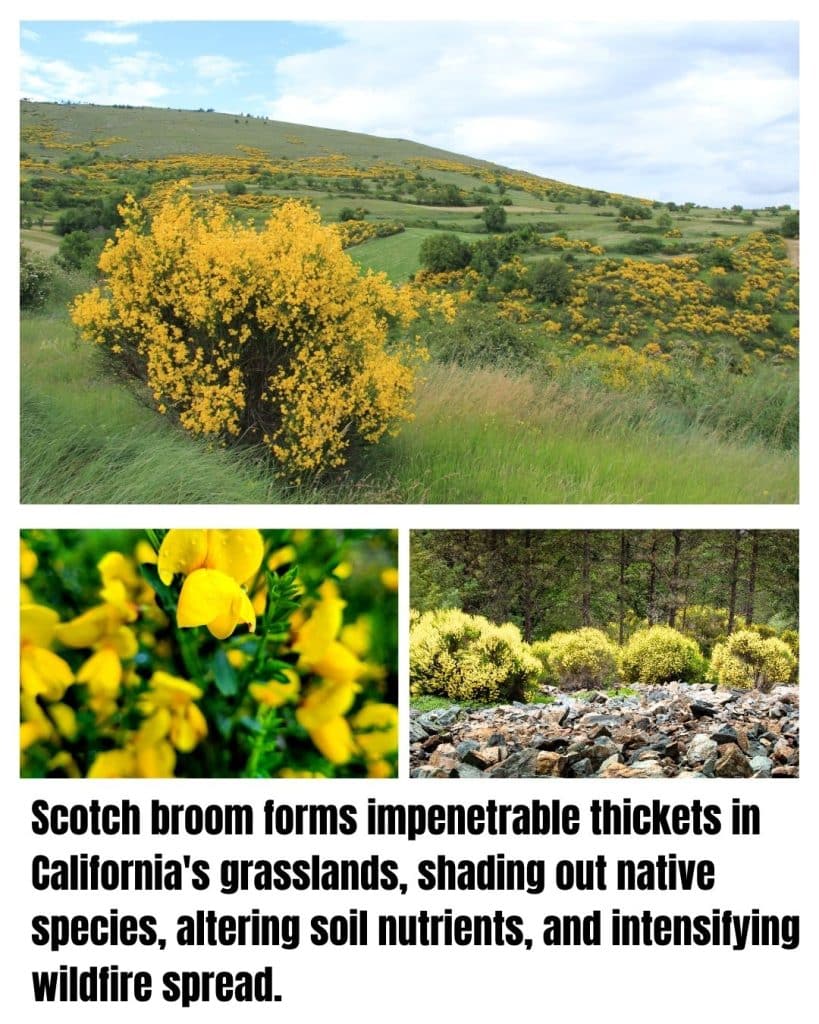

Scotch Broom (Cytisus scoparius)

- Its bright yellow flowers explode like fireworks in spring, attracting pollinators from afar.

- The seeds can “pop” out of pods with a audible snap, shooting up to 12 feet away!

- It’s toxic to livestock, yet some cultures use it in traditional medicine.

Originally from Europe, Scotch broom was brought to California in the 1800s as an ornamental plant and for soil stabilization.

It forms dense thickets that shade out native plants, reducing biodiversity in grasslands and forests.

Its nitrogen-fixing ability alters soil chemistry, making it harder for locals to recover, and it fuels intense wildfires while costing hefty sums in removal.

Himalayan Blackberry (Rubus armeniacus)

- Those juicy berries are delicious in pies, but they’re armed with thorny canes up to 40 feet long!

- One plant can produce thousands of seeds that remain viable in the soil for years.

- Birds and animals spread its seeds far and wide, turning it into a fruity invader.

Hailing from Armenia and surrounding areas, it was introduced to the U.S. in the late 1800s for fruit production and escaped cultivation in California.

In California, it overruns streambanks and forests, forming impenetrable thickets that block access and outcompete natives.

This leads to soil erosion, reduced wildlife habitat, and challenges for recreation, with control efforts straining resources.

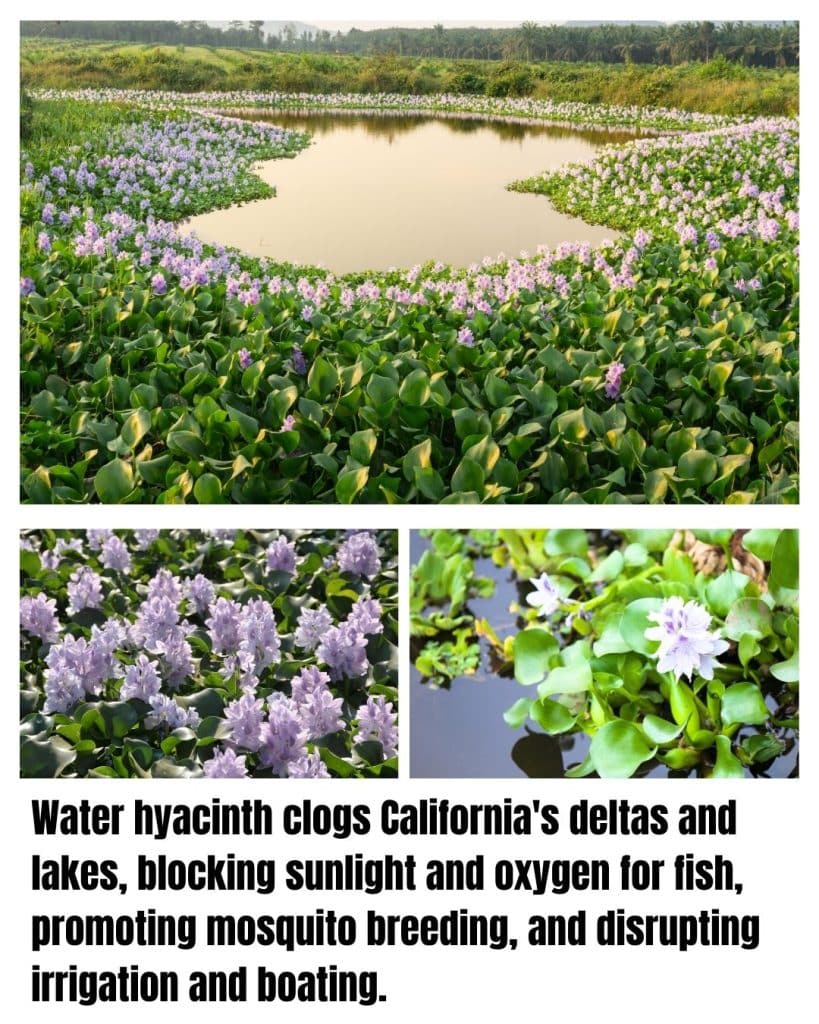

Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes)

- It can double its population in just a week under ideal conditions—what a speedy multiplier!

- Its beautiful lavender flowers hide roots that provide shelter for mosquito larvae.

- Native Amazonians use it for weaving baskets and even as animal feed.

Native to South America, water hyacinth was introduced to California via the aquarium trade and ornamental ponds in the late 1800s.

It clogs waterways, blocking sunlight and oxygen for aquatic life, leading to fish kills and disrupted ecosystems.

Navigation and irrigation suffer, costing millions, while it harbors pests in deltas and lakes.

It also alters water chemistry, exacerbating algae blooms/s

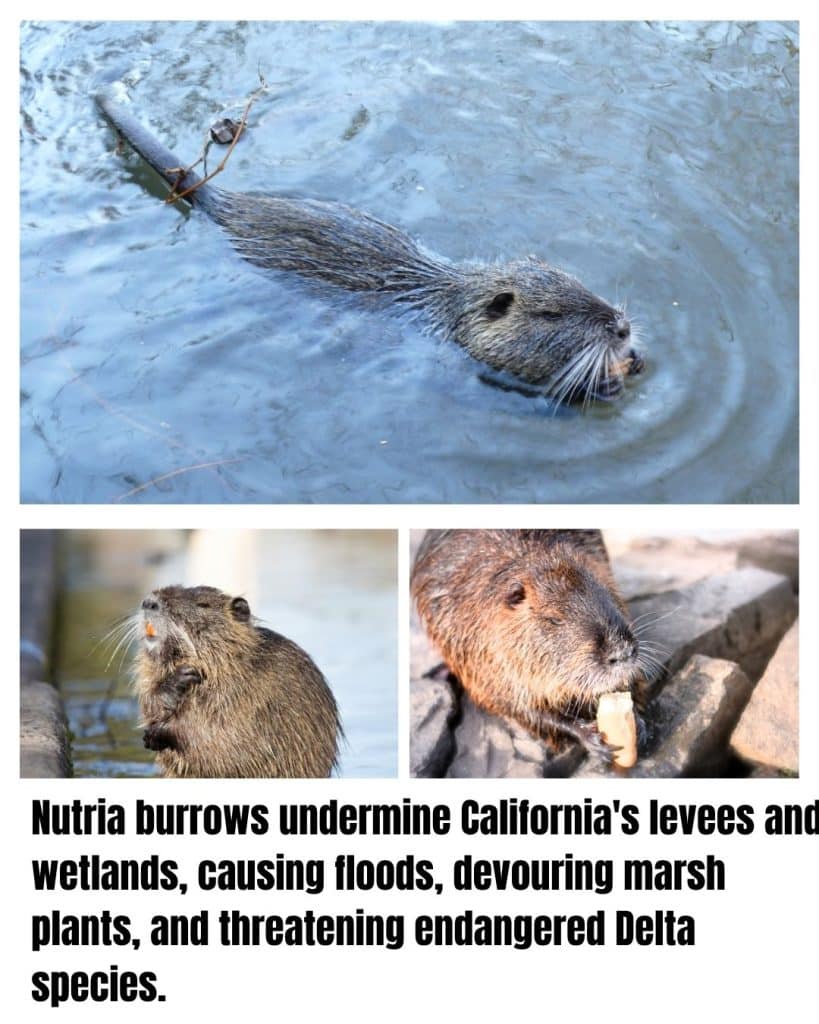

Nutria (Myocastor coypus)

- These “river rats” have orange teeth from iron-rich enamel—super chompers!

- Females can have up to three litters a year, with 13 pups each.

- Their webbed feet make them expert swimmers, like aquatic acrobats.

Native to South America, nutria were introduced to California in the 1890s for fur farming and escaped.

They burrow into levees, causing floods and erosion in wetlands. Devouring vegetation, they destroy marshes vital for birds and fish, threatening the Delta’s fragile ecosystem and agriculture.

Eradication efforts are ongoing, but their rapid reproduction makes it tough.

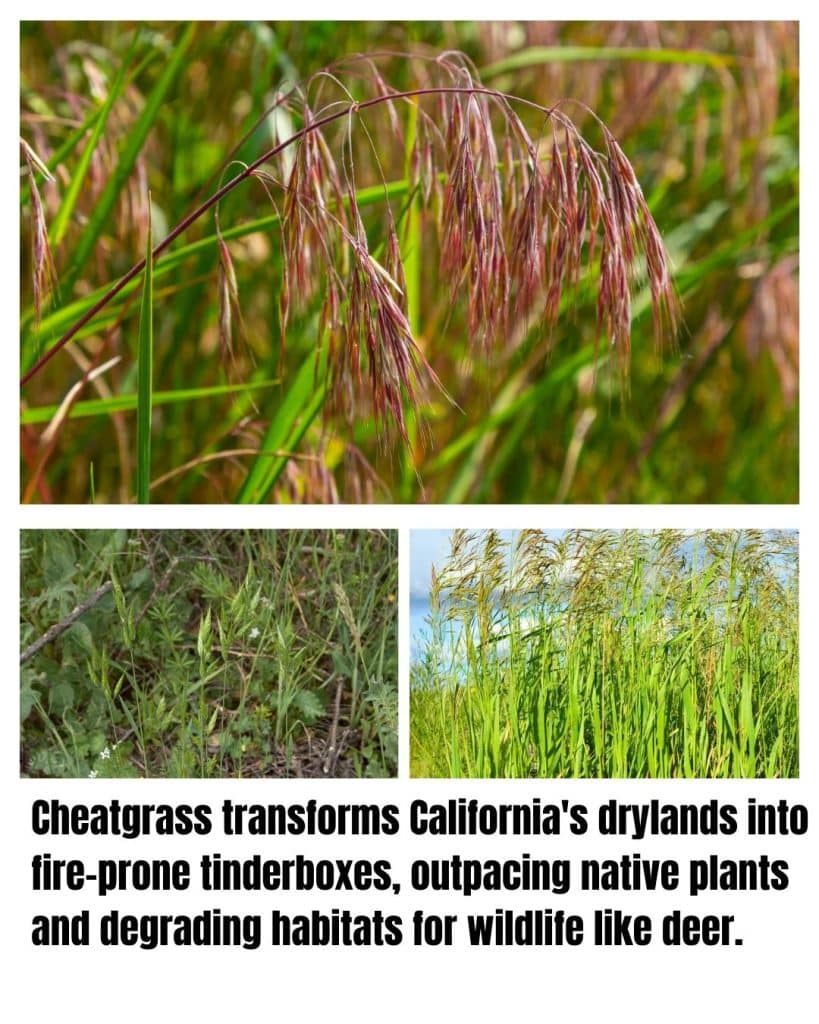

Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum)

- This grass turns reddish-purple in summer, painting hillsides in fiery hues.

- Its seeds have sharp awns that hitchhike on socks and animal fur for dispersal.

- It completes its life cycle super fast, outpacing natives in dry climates.

From Europe and Asia, cheatgrass arrived in California in the late 1800s as a contaminant in grain shipments.

It dominates rangelands, increasing wildfire frequency by drying out early and providing fine fuel.

This harms sagebrush ecosystems, reduces forage for wildlife like mule deer, and promotes soil erosion across vast acres.

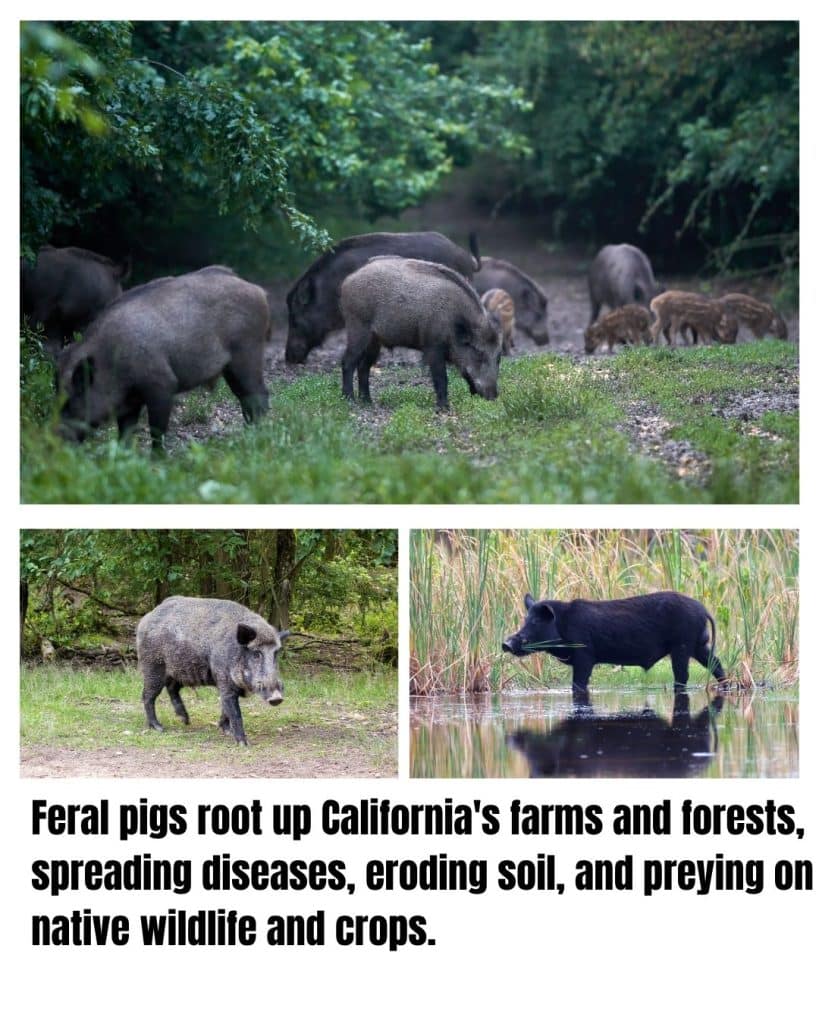

Feral Pig (Sus scrofa)

- These wild boars can run up to 30 mph—faster than you think!

- They have a keen sense of smell, rooting up soil like living plows.

- One sow can produce 10-12 piglets twice a year.

Descended from Eurasian wild boars and domestic pigs, they were introduced by Spanish explorers in the 1500s and later for hunting.

In California, they damage crops, spread diseases to livestock, and root up native plants, leading to erosion and habitat loss for endangered species.

They also prey on ground-nesting birds and compete with natives like deer.

Pampas Grass (Cortaderia selloana)

- Its fluffy plumes can reach 10 feet tall, waving like feathery flags in the wind.

- One plant produces millions of wind-dispersed seeds, traveling miles away.

- It’s popular in floral arrangements, but handling it can cause cuts from sharp leaves.

Native to South America, pampas grass was imported to California in the 1800s for ornamental landscaping.

It invades coastal dunes and grasslands, displacing natives and reducing habitat for birds and butterflies.

Its dense growth increases fire hazards and is tough to eradicate, impacting scenic and ecological values.

House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)

- These little birds build nests in any crevice, even traffic lights!

- Males have “bibs” that grow darker with age and status.

- They thrive near humans, eating almost anything.

Native to Eurasia, it was introduced to the 1850s U.S. for pest control and nostalgia, reaching California soon after.

They bully native birds from feeders and nests, decreasing diversity. Grain and fruit damage affects farms.

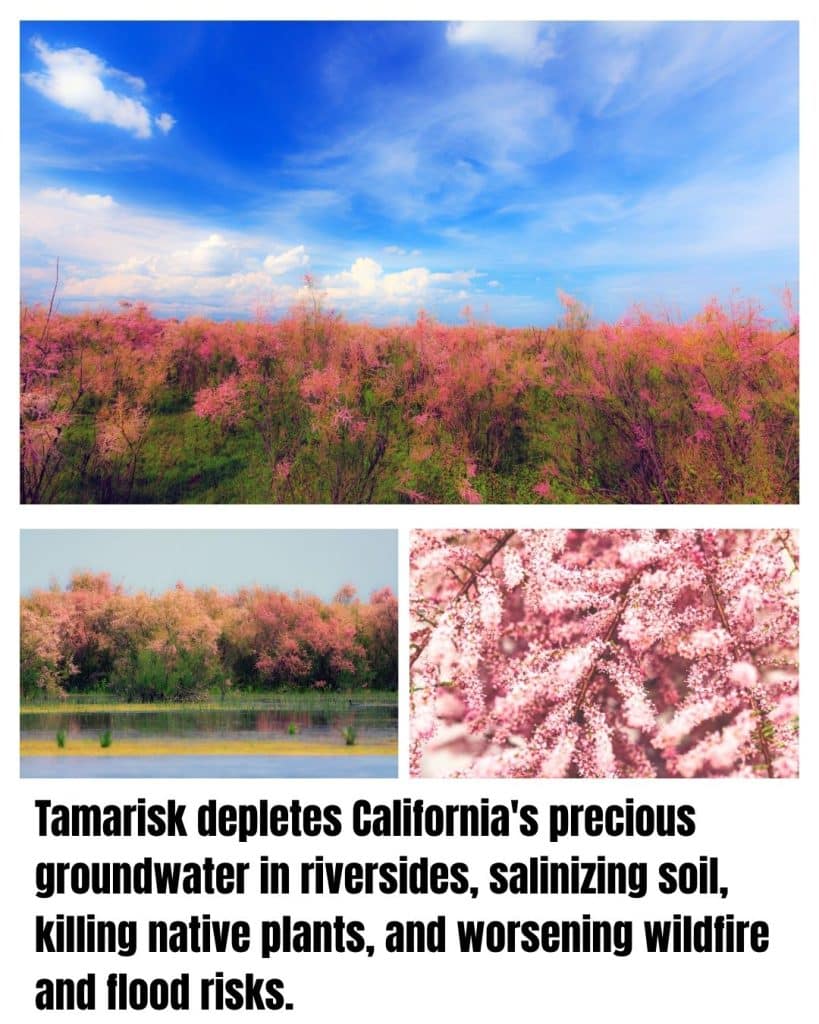

Tamarisk (Tamarix ramosissima)

- Also called saltcedar, it excretes salt from leaves, salting the earth like a natural saboteur.

- Its pink flowers attract bees, but it consumes up to 200 gallons of water per day!

- Ancient Egyptians used it for making tools and medicine.

From Eurasia and Africa, tamarisk was introduced in the 1800s for windbreaks and erosion control.

In California, it invades riparian zones, depleting groundwater and altering habitats for fish and birds.

Increased salinity kills natives, and it promotes wildfires while complicating flood management.

Mute Swan (Cygnus color)

- They can weigh up to 25 pounds with an 8-foot wingspan—swan dive champs!

- Despite being called “mute,” they grunt and hiss when angry.

- Pairs mate for life, dancing in beautiful courtship.

From Europe, introduced in the 1800s for ornamental ponds, escaping to wild.

In CA, they uproot aquatic plants, degrading wetlands and competing with native waterfowl.

Aggressive behavior displaces locals.

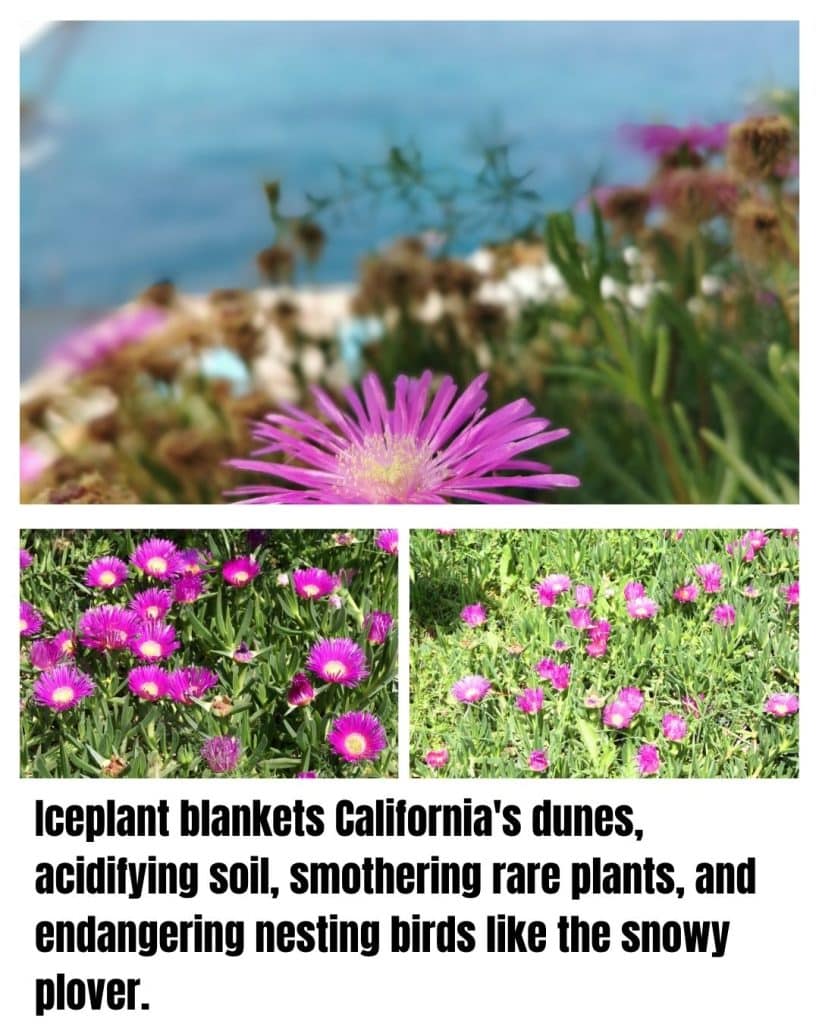

Iceplant (Carpobrotus edulis)

- Its succulent leaves store water, making it drought-resistant like a desert camel.

- Bright daisy-like flowers bloom year-round, adding color to coastal bluffs.

- It’s edible—leaves taste salty and can be pickled!

Originally from South Africa, iceplant was planted in California in the early 1900s for highway stabilization.

It forms mats that smother native dune plants, reducing biodiversity and habitat for endangered species like the snowy plover.

Soil acidification and erosion follow, threatening coastal ecosystems.

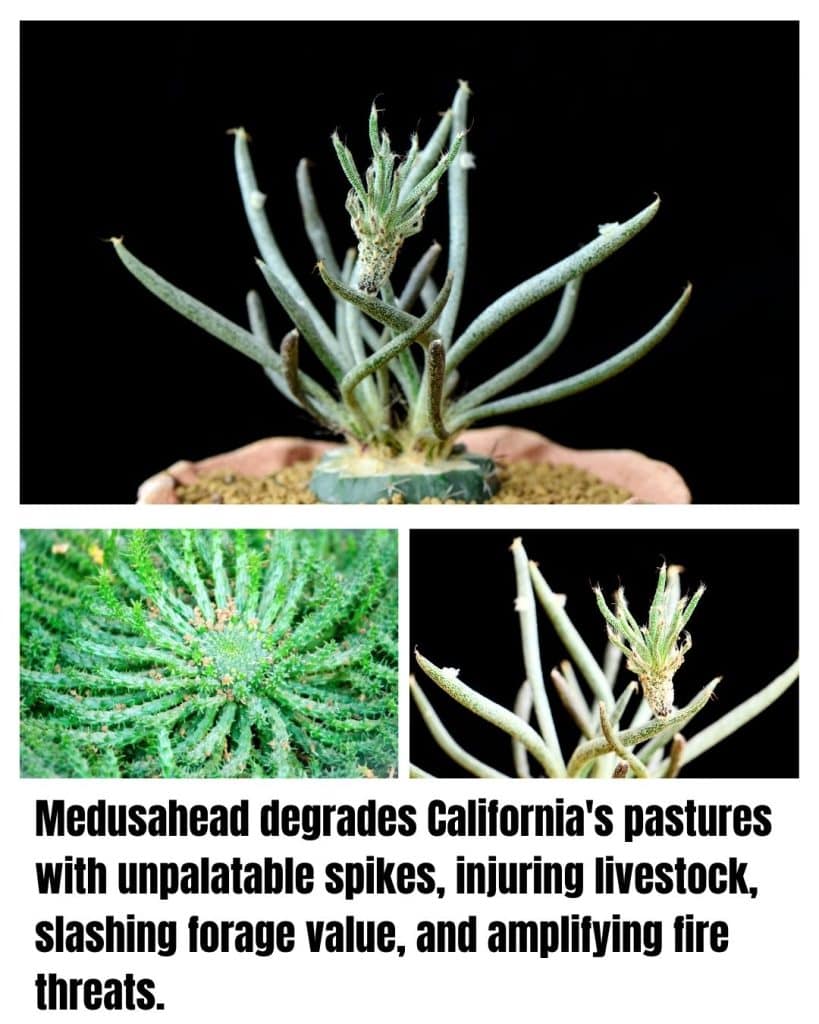

Medusahead (Elymus caput-medusae)

- Named for its spiky seed heads resembling Medusa’s snakes—scary and sticky!

- It contains silica, making it unpalatable to most grazers.

- Seeds can survive in soil for up to 10 years, waiting to strike.

Native to the Mediterranean, medusahead entered California in the late 1800s via contaminated feed.

It outcompetes native grasses in rangelands, degrading pastures and increasing fire risks.

Wildlife forage declines, and its sharp awns injure animals, costing ranchers dearly.

American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus)

- They croak so loud it’s like a mile away—bass vocalists!

- Tadpoles can take two years to metamorphose.

- Adults gobble insects, birds, and even other frogs.

Native to eastern U.S., introduced to California in the 1890s for food. 22

They prey on native amphibians, spreading diseases like chytrid fungus, decimating populations in ponds and streams.

Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans)

- Their red ear stripes glow like racing stripes!

- They bask in groups, stacking like turtle towers.

- Females lay up to 30 eggs per clutch.

From the southern U.S., released from pet trade in California since the 1900s. 22

They outcompete native turtles for food and basking sites, spreading salmonella and altering aquatic habitats.

Brown Trout (Salmo trutta)

- They can jump waterfalls up to 6 feet high—salmon rivals!

- Anglers prize them for their fighting spirit.

- Colors change with mood and environment.

Native to Europe, they were introduced in the 1800s for sport fishing.

In CA streams, they prey on native trout like golden trout, hybridizing and reducing pure populations.

Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio)

- They live up to 20 years and grow to 4 feet—pond giants!

- Bottom-feeders, stirring mud like underwater vacuums.

- Goldfish are their domesticated cousins.

From Asia and Europe, they were introduced in the 1800s for food.

They muddy the waters, reducing clarity and plant growth, harming native fish in lakes and rivers.

Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorpha)

- Each can filter a liter of water daily—tiny purifiers gone wrong!

- Females release a million eggs yearly.

- They attach to anything, including each other.

Native to Eurasia, arrived via ballast water in the 1980s, threatening CA.

They clog pipes and intakes, costing infrastructure billions, and outcompete natives for plankton.

European Green Crab (Carcinus maenas)

- They change color to match surroundings—camouflage experts!

- One crab eats 40 clams a day.

- Migrated across oceans in ship hulls.

From Europe, arrived in San Francisco Bay in 1989 via ballast.

They devour shellfish, disrupting fisheries and food webs in estuaries.

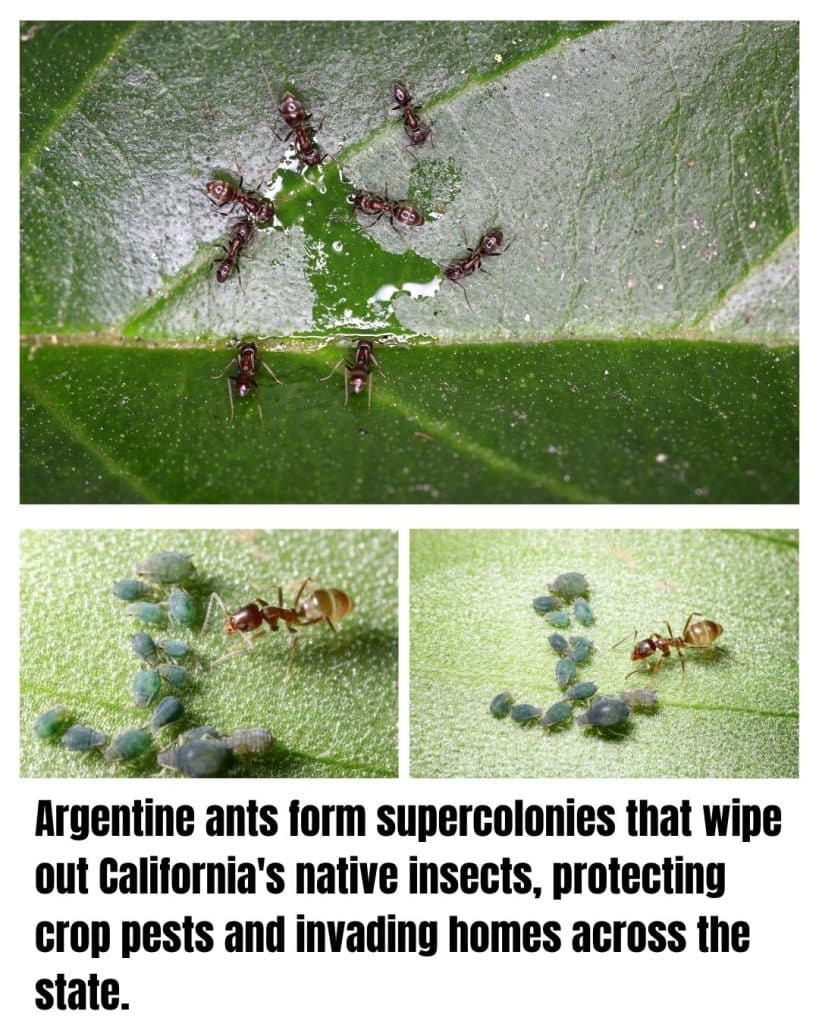

Argentine Ant (Linepithema humile)

- They form supercolonies with millions, no fighting among nests.

- Milk aphids for honeydew like tiny farmers.

- Travel in trails miles long.

From South America, shipped in cargo to CA in the 1900s.

Outcompete native ants, reducing insect diversity, and spreading pests in urban and wild areas.

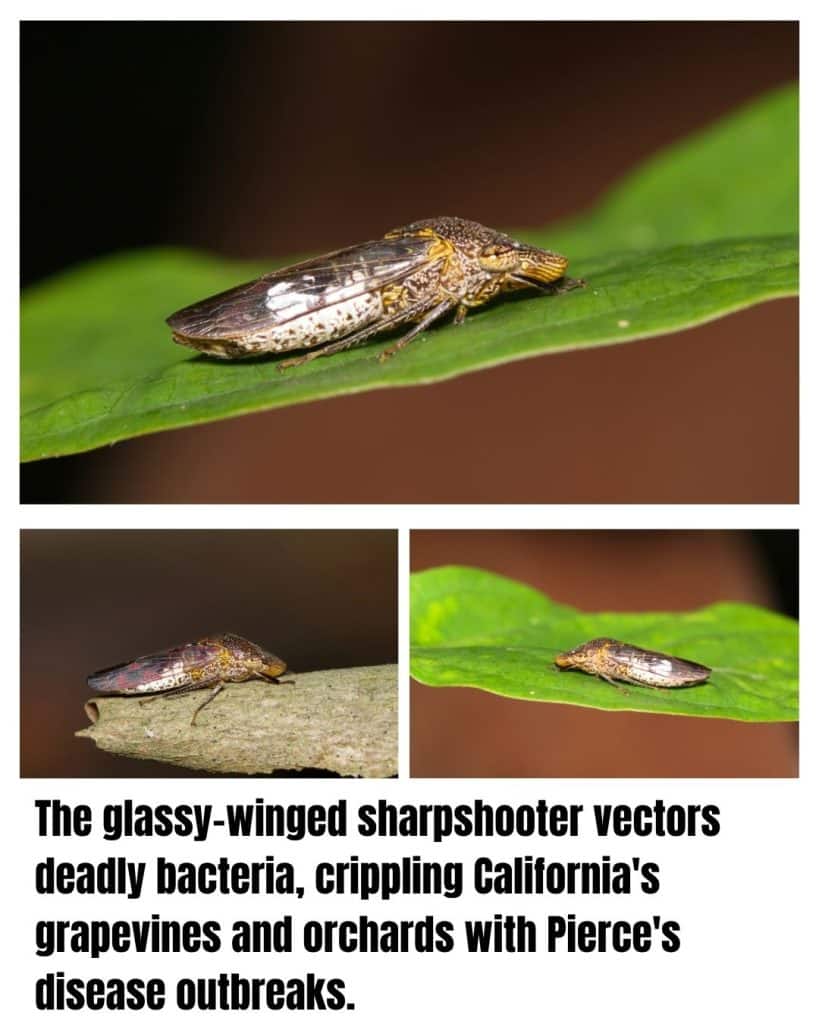

Glassy-Winged Sharpshooter (Homalodisca vitripennis)

- They “shoot” excrement up to 300 times their body length!

- Pierce plants with their needle mouths.

- Vectors for deadly bacteria.

From the southeastern U.S., and arrived in the 1990s on plants.

Spreads Pierce’s disease, devastating vineyards and orchards.

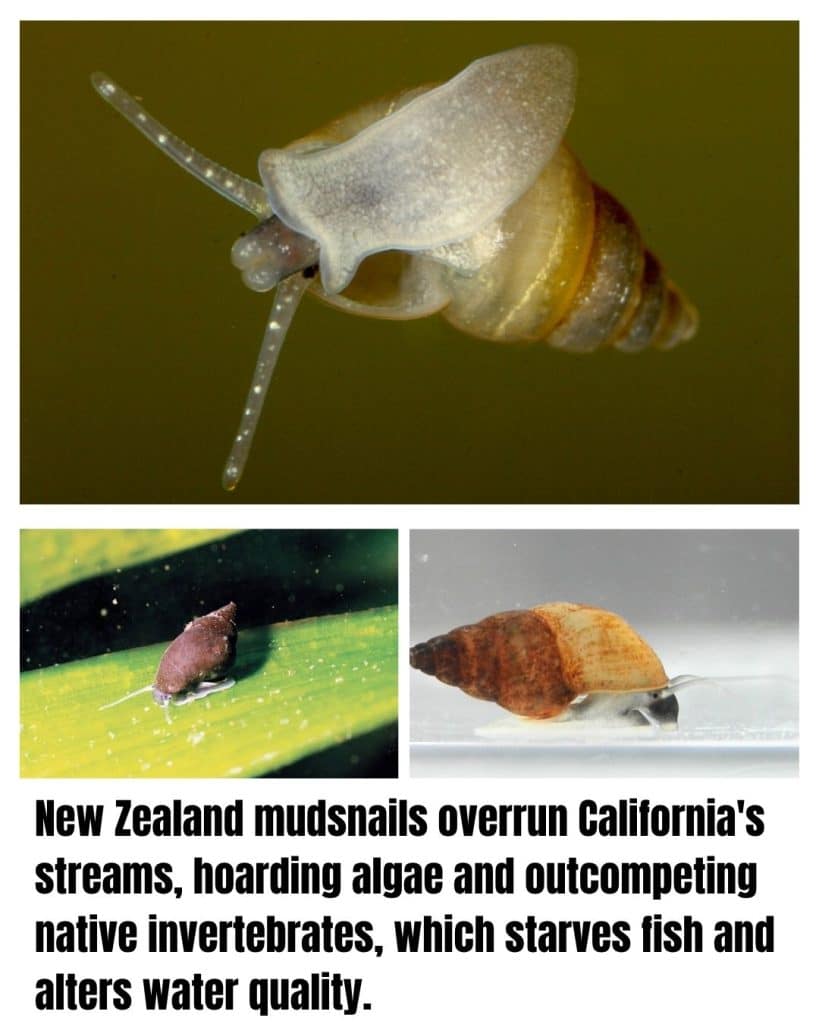

New Zealand Mudsnail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum)

- Females clone themselves—no males needed!

- Tiny, but densities reach 500,000 per square meter.

- Survive in fish guts for dispersal.

From New Zealand, likely via aquarium or fishing gear.

Clogs streams, outcompeting natives for algae, altering food chains.

Thanks for joining me on this eye-opening tour of California’s invasive species! By recognizing these troublemakers, you’re helping protect our state’s precious natural heritage. Share what you’ve learned, support local removal efforts, and stay vigilant. Together, we can keep California wild and wonderful.