Arkansas’s landscapes are under siege, from the skies to the streams. Invasive species are crowding out natives, wrecking crops, and spreading disease.

Some were brought here on purpose. Others hitchhiked in unnoticed. Now they’re everywhere. Birds, bugs, beasts, and plants; all reshaping our forests, farms, and waterways in ways we can’t ignore.

Invasive Birds (Terrestrial)

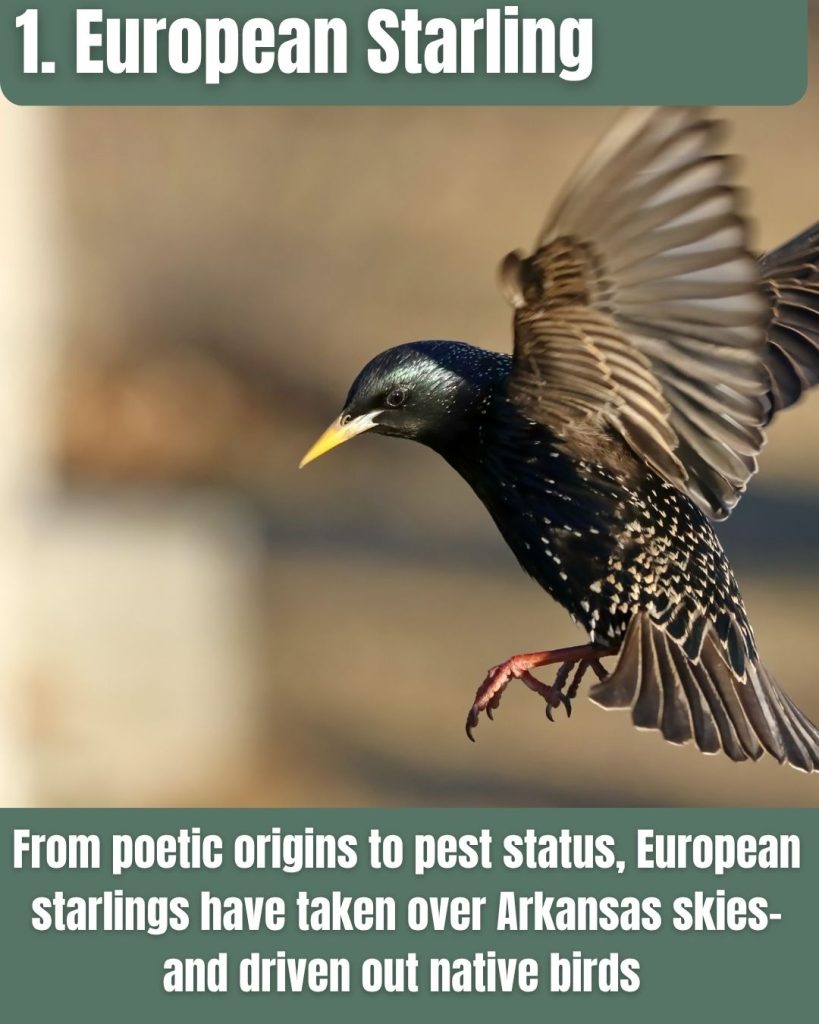

European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

- Shakespeare’s mistake: Introduced in the 1890s by a group trying to release every bird mentioned by Shakespeare.

- Bird bullies: Take over nest cavities from native species like bluebirds and woodpeckers.

- Farm flock disasters: Gather in massive groups that destroy crops, contaminate livestock feed, and cause millions in ag losses.

Introduced in 1890 as part of a misguided plan to release every bird mentioned by Shakespeare, European starlings now number in the hundreds of millions across Arkansas.

They seize nest cavities before bluebirds and woodpeckers can claim them, then descend in vast flocks that foul feedlots and cost U.S. agriculture an estimated $800 million a year by damaging grain and contaminating livestock feed.

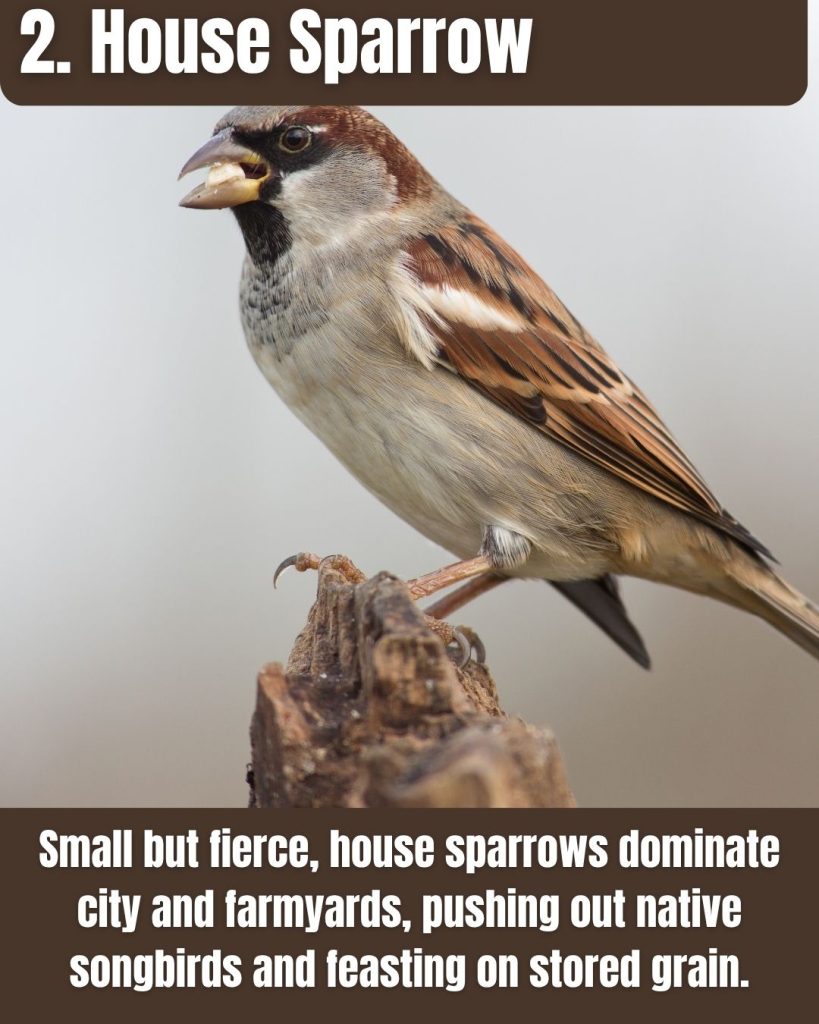

House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)

- Urban invaders: Thrive near people and buildings, now common across Arkansas towns and farms.

- Aggressive squatters: Attack and evict native birds from nest boxes, sometimes killing them to take over.

- Reproduction machines: Raise multiple broods a year, quickly overwhelming native songbird populations.

Brought from Europe in the 1800s to eat urban insects (a job they barely perform), the plucky house sparrow has become one of Arkansas’s most common birds.

Fiercely territorial, it drives native songbirds from nest boxes and happily pecks grain from silos, barns, and even livestock troughs, leaving contaminated feed and feathered skirmishes in its wake.

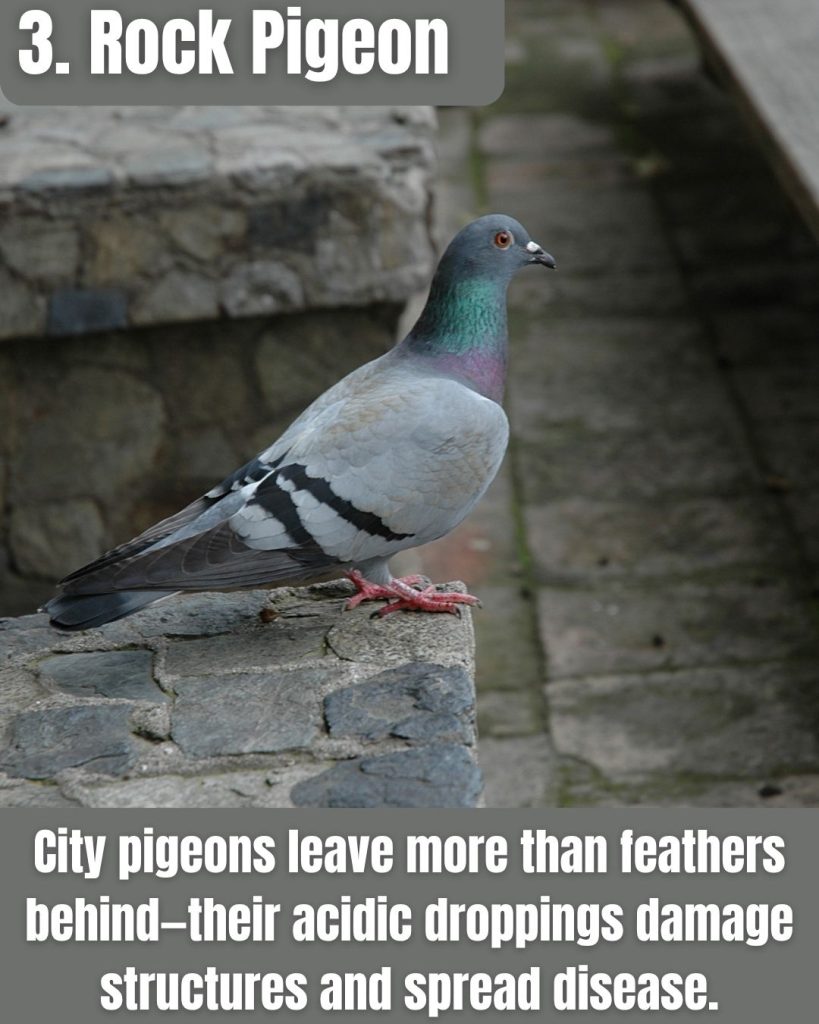

Rock Pigeon (Columba livia)

- Urban dwellers: Found roosting on buildings, bridges, and ledges in towns across Arkansas.

- Structural damage: Acidic droppings corrode stone, metal, and paint on buildings.

- Disease spreaders: Can carry parasites and diseases that affect humans and native birds.

Descended from Old-World homing pigeons, the familiar city pigeon congregates on bridges, barns, and courthouse roofs.

Acidic droppings corrode stone and metal, while large flocks displace native doves and spread parasites that can also infect people.

A centuries-old introduction, pigeons remain a modern urban headache.

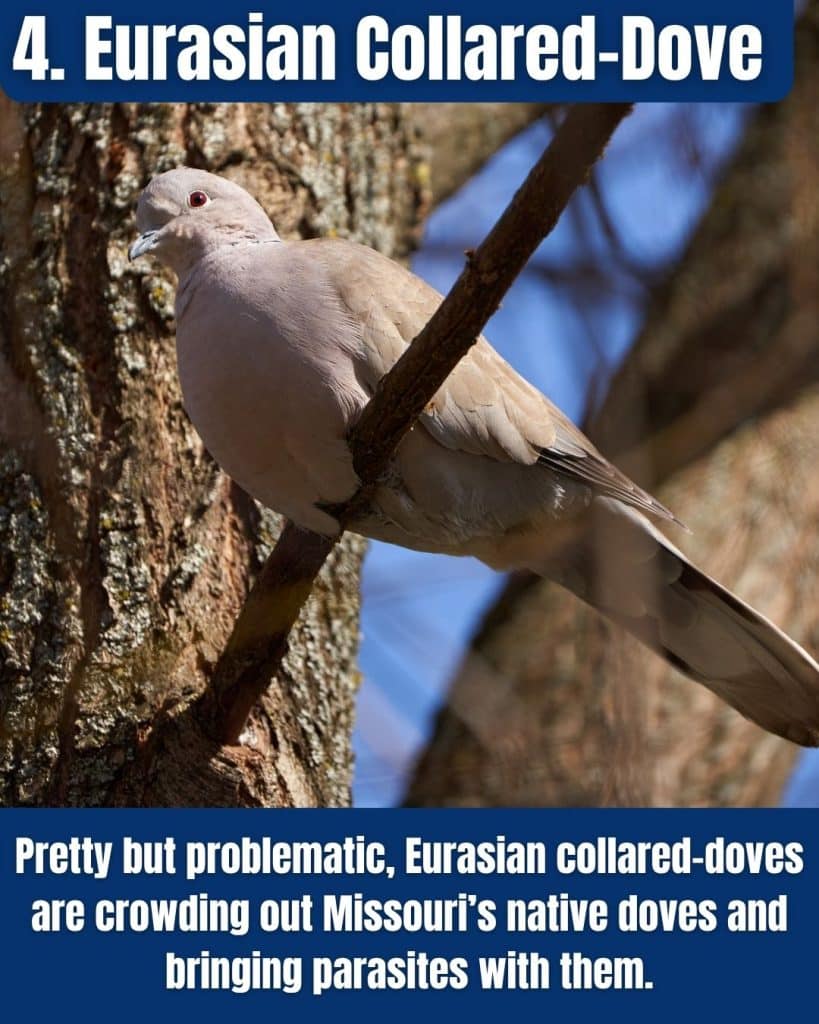

Eurasian Collared-Dove (Streptopelia decaocto)

- Recent arrival, rapid spread: First showed up in Arkansas in the 1990s and is now common in towns and farms.

- Native dove rival: Competes with mourning doves for food, feeders, and nesting spots.

- Disease carrier: Can transmit parasites like Trichomonas, threatening native doves and the hawks that eat them.

First released in the Bahamas in the 1970s, collared-doves reached Arkansas by the late 1990s.

They breed almost year-round, crowding backyards and competing with mourning doves at feeders and nest sites.

Their tame demeanor around people, and their rapid population boom, explain why they now rank among the fastest-spreading invasive birds in North America.

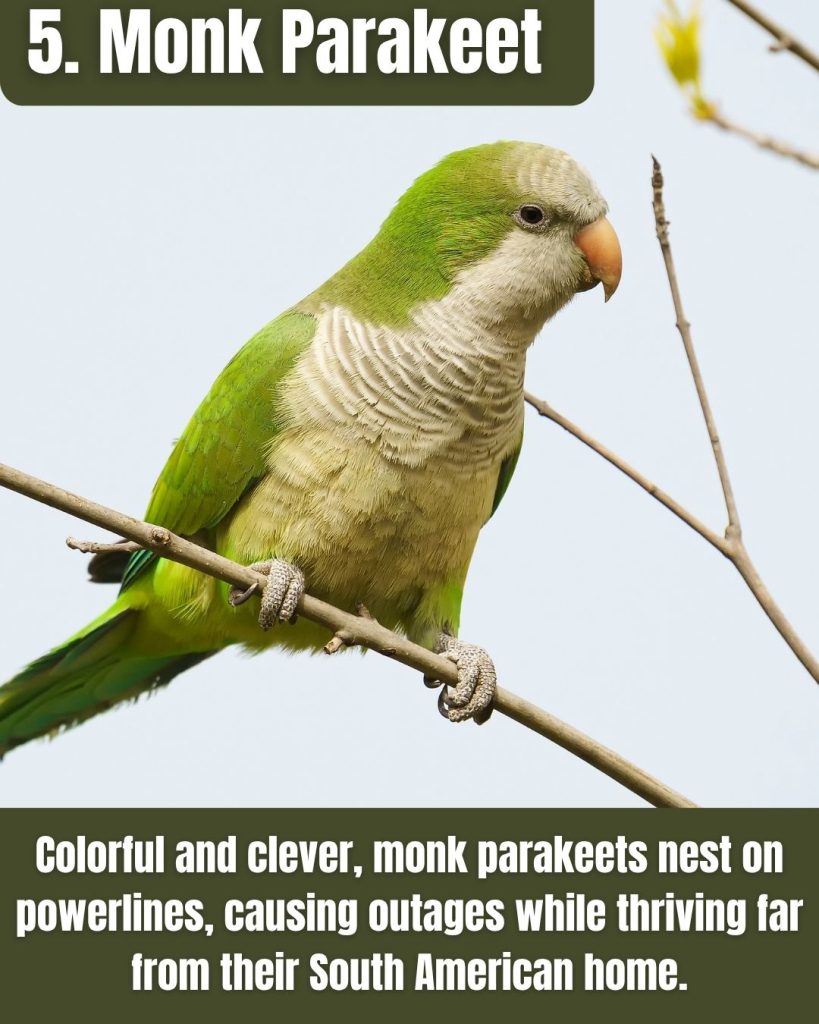

Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus)

- Colorful troublemaker: Bright green parrots that build large communal nests on utility poles.

- Powerline pests: Nests can cause electrical outages and fires.

- Cold survivors: Adapted to colder climates, they survive Arkansas winters by huddling in groups.

Originally from South America, monk parakeets have escaped captivity and established wild colonies in parts of Arkansas.

They build bulky stick nests on power infrastructure, creating costly maintenance problems and safety risks.

Invasive Insects

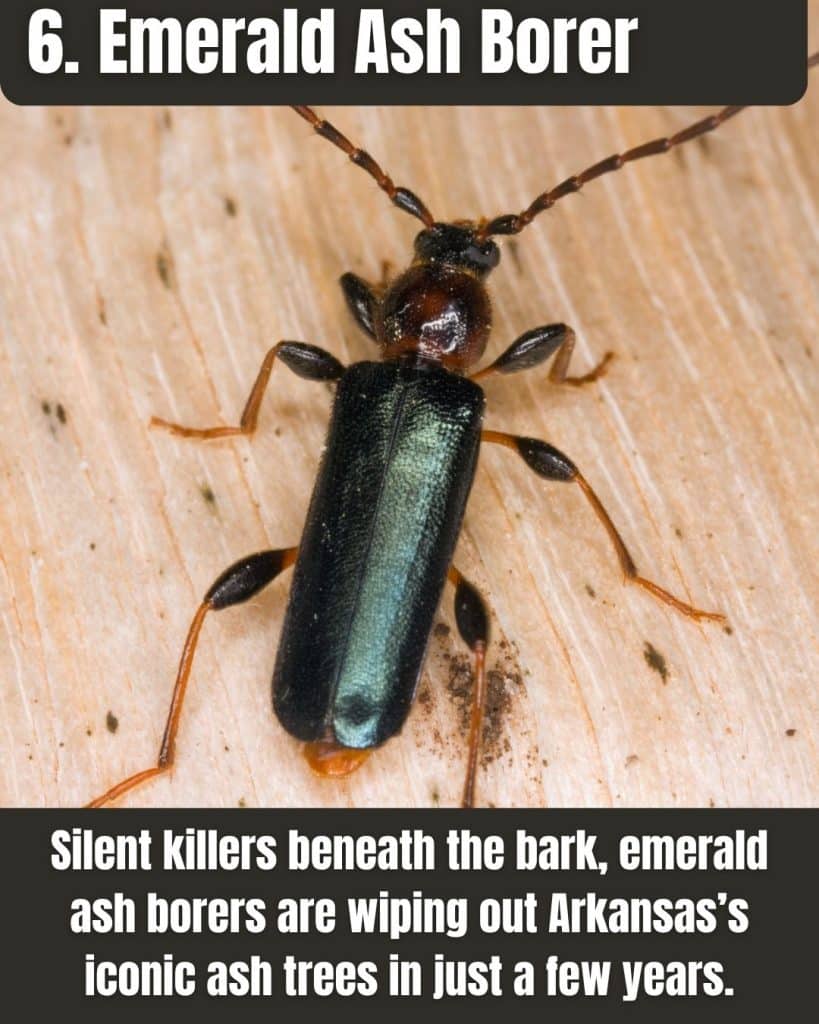

Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis)

- Ash tree killer: Larvae tunnel under bark, cutting off nutrients and killing trees within 2-3 years.

- Widespread threat: Detected in Arkansas since the early 2010s, now found across much of the state.

- Irreplaceable loss: Endangers Arkansas’s ash trees, which provide shade, lumber, and vital habitat for wildlife.

Metal-green and only half an inch long, the emerald ash borer has killed millions of ash trees since reaching Arkansas.

Its larvae tunnel beneath bark, girdling trees that once shaded streets and forests; without intervention, foresters warn it could eliminate ash statewide.

Firewood quarantines and imported parasitic wasps are the main lines of defense.

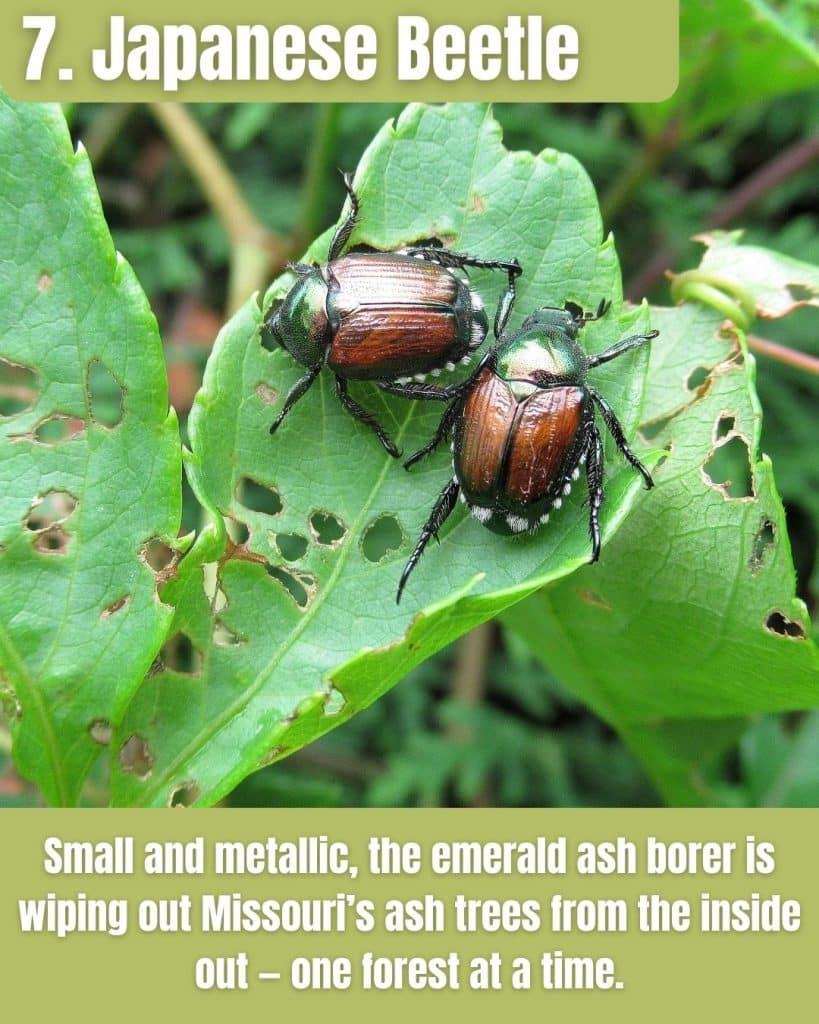

Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica)

- Leaf skeletonizer: Adults chew through flowers, leaves, and fruit, leaving behind lacy, brown foliage.

- Lawn destroyer: Grubs feed on grass roots, turning lawns and pastures into dead, patchy messes.

- Hard to stop: Highly mobile and feeds on 300+ plant species, including roses, corn, soybeans, and grapes.

Since appearing in the southeastern U.S., including Arkansas, this iridescent beetle has marched across the state.

Adults gather in hordes to skeletonize roses, soybeans, grapes, and more, turning leaves into lace.

Populations boom every few summers, challenging gardeners and farmers who juggle traps, row covers, and timely insecticides.

Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Halyomorpha halys)

- Crop puncturers: Feed by piercing fruit and vegetable skins, causing unsightly scars and crop loss.

- Winter house guests: Seek shelter indoors during cold months, often invading homes in large numbers.

- Global hitchhikers: Spread unintentionally via transported goods, vehicles, and firewood.

Confirmed in Arkansas in the 2010s, the brown marmorated stink bug punctures fruit and vegetable skins, leaving corky scars that make produce unsellable.

Come autumn, thousands invade houses to overwinter, releasing their trademark odor when crushed, an unpleasant reminder of global trade’s stowaways.

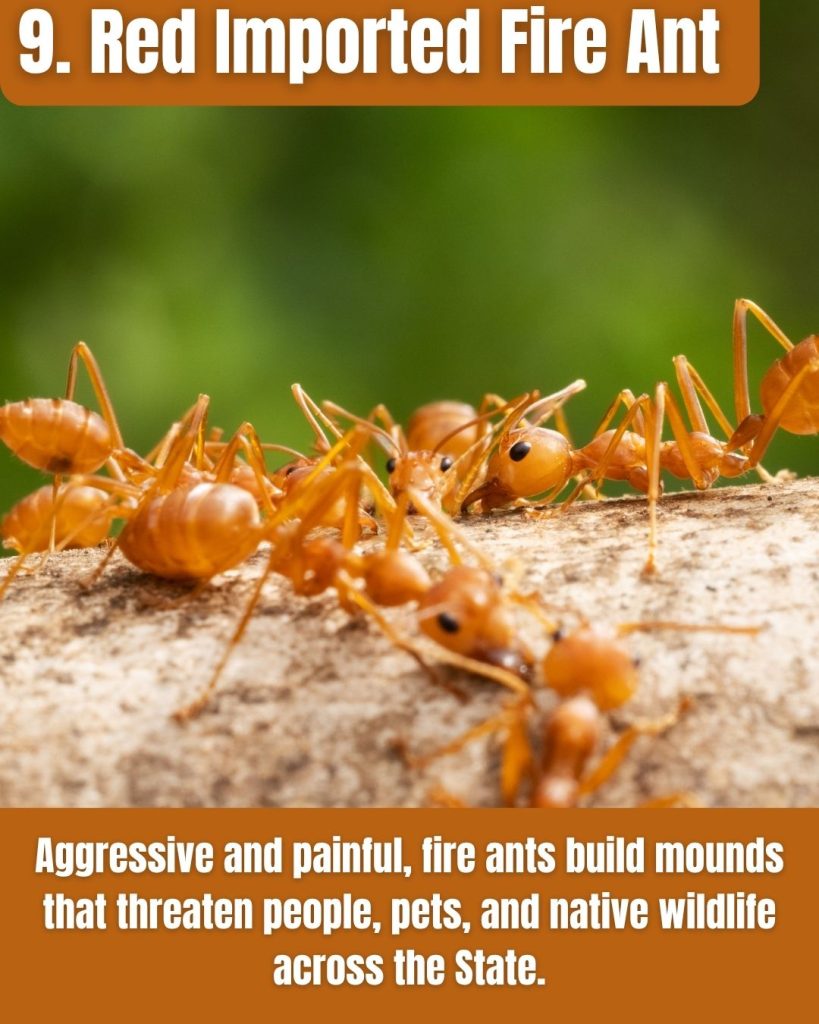

Red Imported Fire Ant (Solenopsis invicta)

- Aggressive invaders: Deliver painful stings that can cause allergic reactions in people and animals.

- Rapid spreaders: Build large mounds that disrupt lawns, pastures, and crop fields.

- Ecosystem disruptors: Outcompete native ants and other insects, altering soil and food webs.

Introduced through ports in the southern U.S., red imported fire ants are now widespread in Arkansas.

Their painful sting and aggressive nature make them a serious pest for homeowners, farmers, and wildlife.

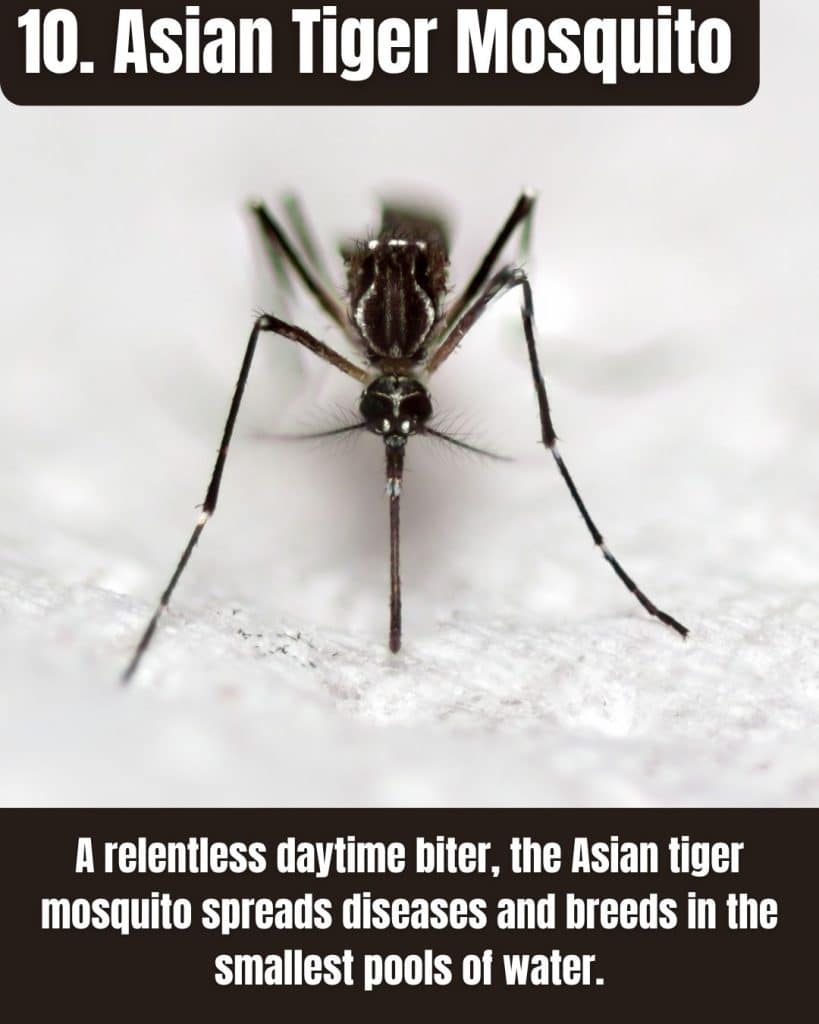

Asian Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus)

- Daytime biter: Unlike most mosquitoes, it’s active during the day, making outdoor time miserable even in sunlight.

- Disease risk: Can carry viruses like Zika, dengue, and West Nile, though transmission in Arkansas is still rare.

- Fast breeder: Lays eggs in tiny amounts of standing water. Even a bottle cap can host larvae.

Hitchhiking to Arkansas in used tire shipments during the 1980s, this day-biting mosquito now buzzes through backyards statewide.

Besides spoiling summer cookouts, it carries West Nile, dengue, and chikungunya viruses and breeds in small containers, from flowerpot saucers to forgotten gutters.

Invasive Animals (Non-Bird, Non-Insect)

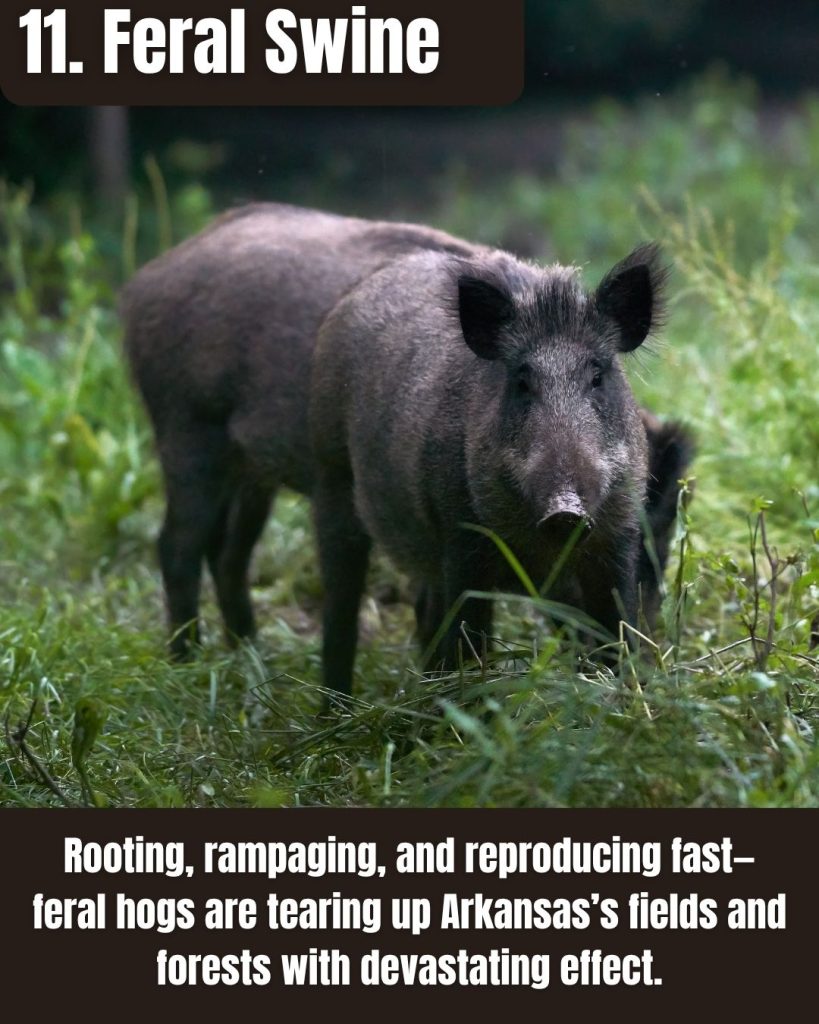

Feral Hog (Sus scrofa)

- Rooting wreckers: Tear up forests, fields, and wetlands, causing erosion, destroying crops, and damaging wildlife habitat.

- Exploding population: Reproduces rapidly. A single sow can produce two litters per year, with up to a dozen piglets.

- Disease risk: Carry harmful diseases like brucellosis and pseudorabies, threatening livestock and native wildlife.

With sows raising multiple litters a year, feral hogs tear up crops, pastures, and forests, rooting like rototillers and muddying streams.

Arkansas’s eradication crews trap entire “sounders,” because scattering them only spreads the problem, and the diseases hogs can pass to livestock and wildlife.

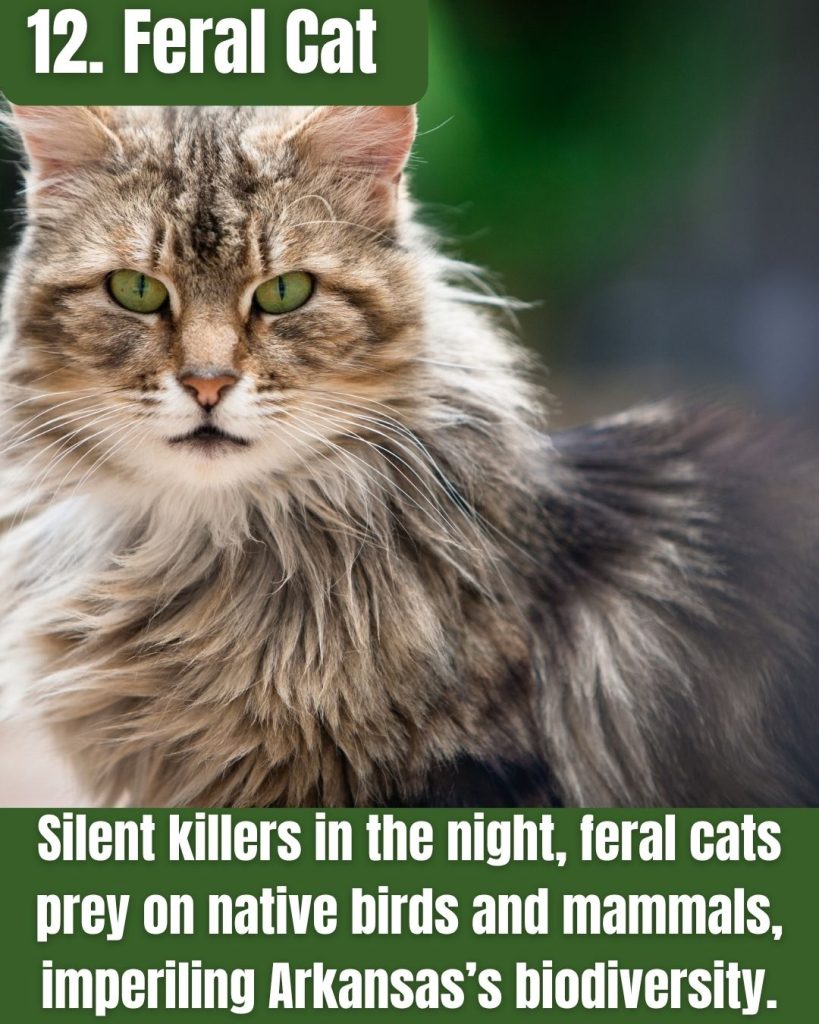

Feral Cat (Felis catus)

- Efficient predators: Kill billions of birds, reptiles, and small mammals annually, many of them native and declining species.

- Hard to manage: Reproduce quickly and often avoid traps, making control efforts difficult in both rural and urban areas.

- Wildlife threat: Considered one of the top invasive species worldwide, they pose a serious risk to Arkansas’s native biodiversity.

Whether abandoned pets or generations-old barn cats, outdoor cats kill an estimated 2.4 billion birds annually in the U.S.

Arkansas’s songbirds, small mammals, and herpetofauna all feel the toll.

Conservationists urge cat owners to keep pets indoors or build “catios” to protect both wildlife and the cats themselves.

Nutria (Myocastor coypus)

- Wetland invaders: Feed heavily on aquatic plants, damaging marshes and riverbanks.

- Burrowing behavior: Dig extensive burrows that weaken levees and cause erosion.

- Rapid breeders: Can produce multiple litters annually, leading to fast population growth.

Escaped South American fur-farm rodents now gnaw Arkansas’s wetlands and riverbanks.

Each 20-pound nutria consumes a quarter of its weight in vegetation daily, turning lush wetlands into open water and weakening levees with burrows.

Mild winters and abundant waterways allow populations to persist and expand.

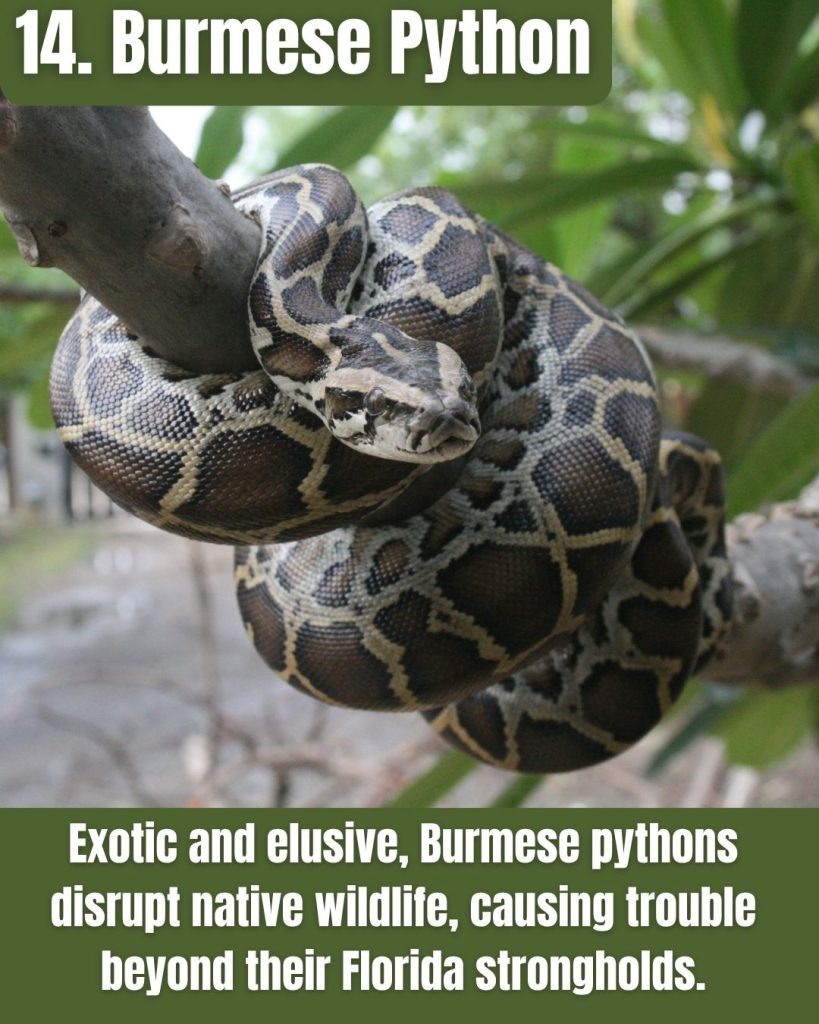

Burmese Python (Python bivittatus)

- Non-native predator: Large constrictors introduced via pet releases, capable of killing deer, alligators, and native wildlife.

- Stealthy hunters: Hard to detect and remove, they disrupt native food chains.

- Reproductive potential: Can produce dozens of eggs per clutch, fueling population growth.

While more notorious in Florida, released Burmese pythons have been reported in southern Arkansas.

Their presence raises concern due to impacts on native reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Norway Rat (Rattus norvegicus)

- City survivors: Thrive in urban Arkansas, from alleyways to barns, chewing through wood, wires, and walls.

- Public health threat: Spread dangerous diseases like salmonella, typhus, and rat-bite fever.

- Livestock menace: Invade poultry houses, eat grain, and have even been known to attack young chicks and piglets.

A stowaway since colonial times, the brown rat infests grain elevators, restaurants, and sewers.

It chews wiring and wood, contaminates food, and spreads diseases such as leptospirosis and salmonellosis.

Rats also raid ground-nesting bird eggs, adding ecological injury to urban insult.

Invasive Terrestrial Plants

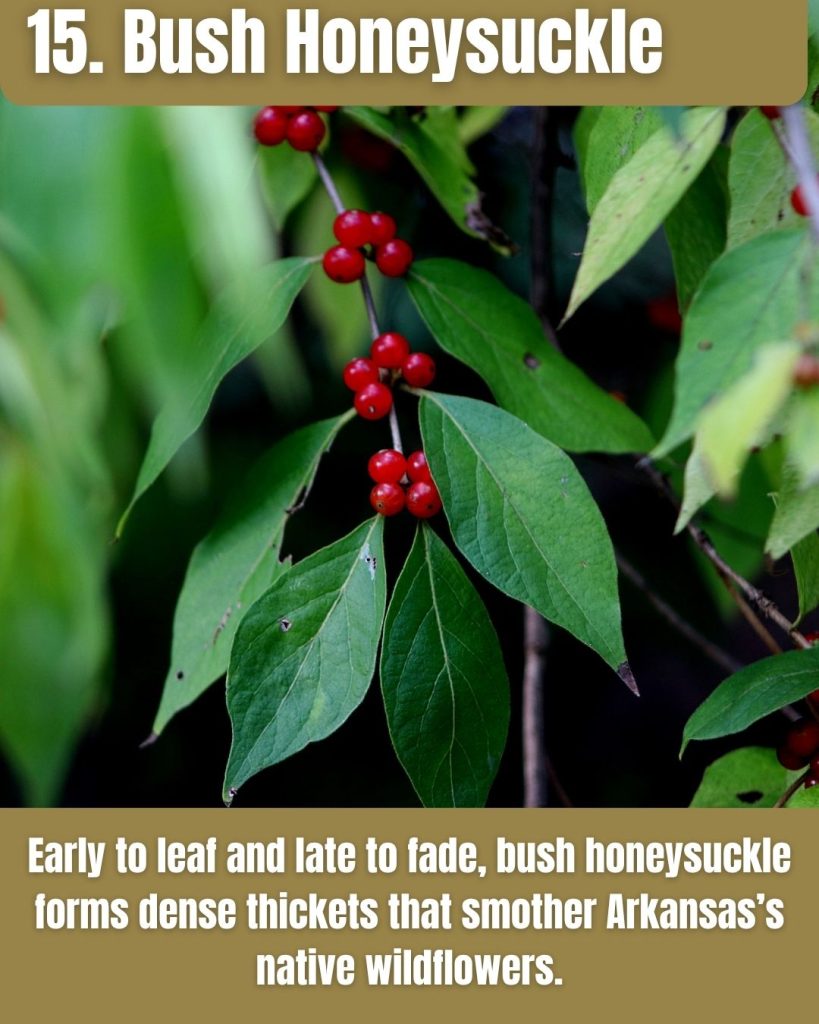

Bush Honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.)

- Early to rise, late to fade: Leaf out earlier and stay green longer than native plants, stealing sunlight and space.

- Wildlife disruptor: Creates dense thickets that crowd out native understory plants and provide poor habitat and nutrition for wildlife.

- Rapid spreader: Birds eat the berries and spread seeds far and wide, helping honeysuckle take over forests, parks, and fencerows.

Leafing out before Arkansas’s spring ephemerals, bush honeysuckle forms dense, shady thickets that starve native wildflowers of light.

Birds spread its nutrient-poor red berries, and the shrub may release soil toxins that further suppress competitors, leaving woodlands quieter and less diverse.

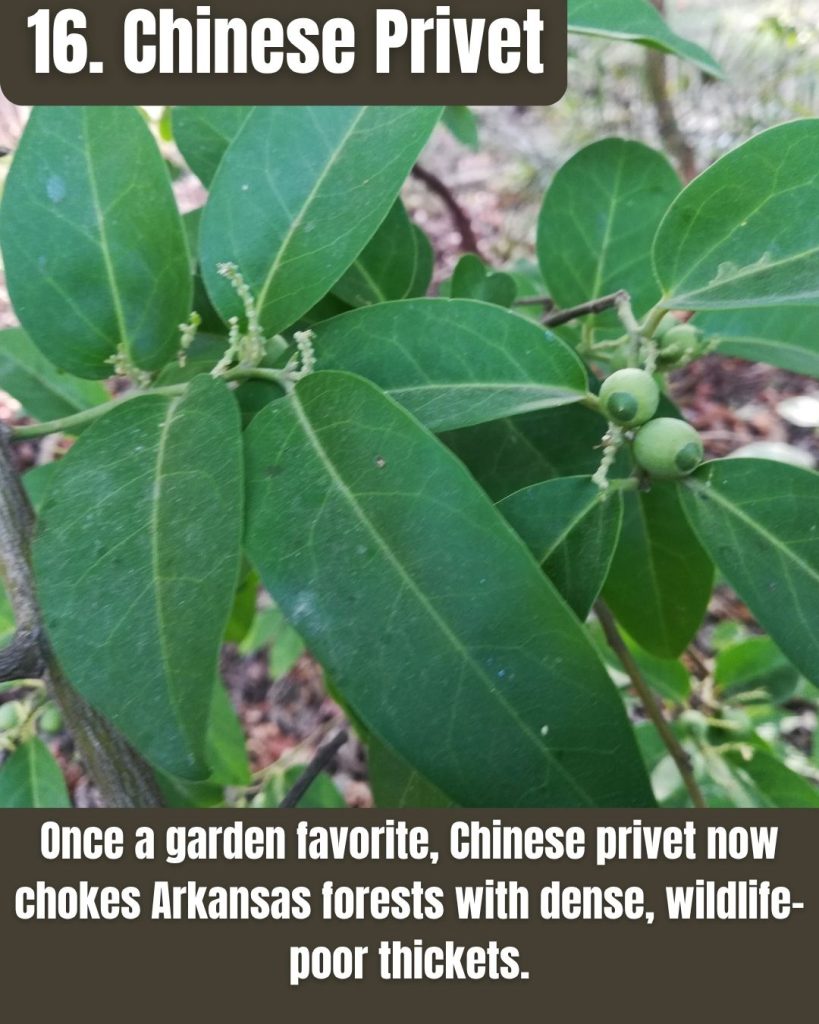

Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense)

- Invasive shrub: Forms dense thickets in Arkansas forests and riparian areas.

- Wildlife impact: Shades out native plants and provides poor food for wildlife.

- Seed spread: Birds disperse berries, accelerating spread across landscapes.

Introduced as an ornamental hedge plant, Chinese privet escaped cultivation and now dominates understories across Arkansas.

It crowds out native plants, disrupting natural ecosystems and reducing biodiversity.

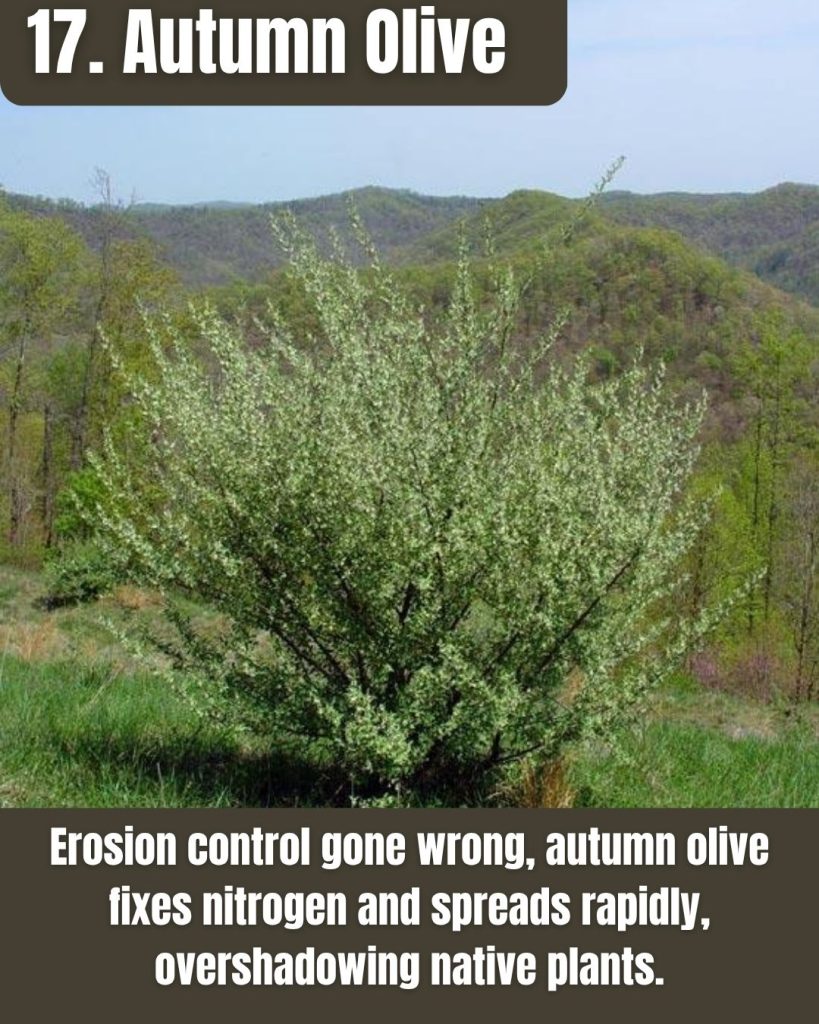

Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata)

- Unwanted comeback story: Introduced for erosion control and wildlife cover, now a top invader in Arkansas fields and roadsides.

- Soil changer: Fixes nitrogen, which alters soil chemistry and gives it an edge over native plants.

- Berry boom: Produces thousands of red berries eaten by birds, spreading it rapidly across the landscape.

Planted for erosion control, autumn olive thrives on poor soils by fixing nitrogen, then overshadows native prairie plants. Stands alter soil chemistry and can even favor mosquito breeding.

Each shrub yields thousands of berries, all too eagerly distributed by songbirds.

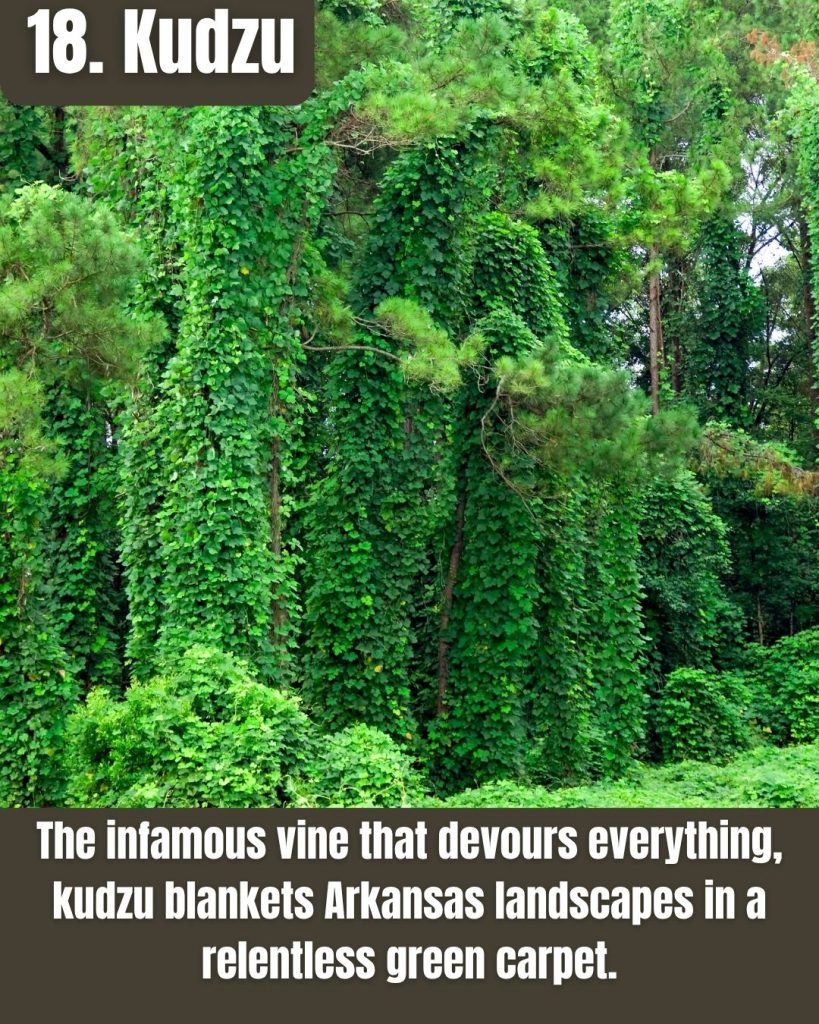

Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata)

- The vine that ate the South: Rapidly growing vine that smothers trees, shrubs, and native plants.

- Erosion risk: Grows on hillsides and roadways, sometimes stabilizing soil but at the cost of native vegetation.

- Difficult control: Resprouts from roots, requiring repeated treatments and mowing.

Kudzu is infamous across Arkansas for engulfing forests, fences, and powerlines in dense green blankets.

Though once promoted for erosion control, its invasive nature threatens native plants and habitats statewide.

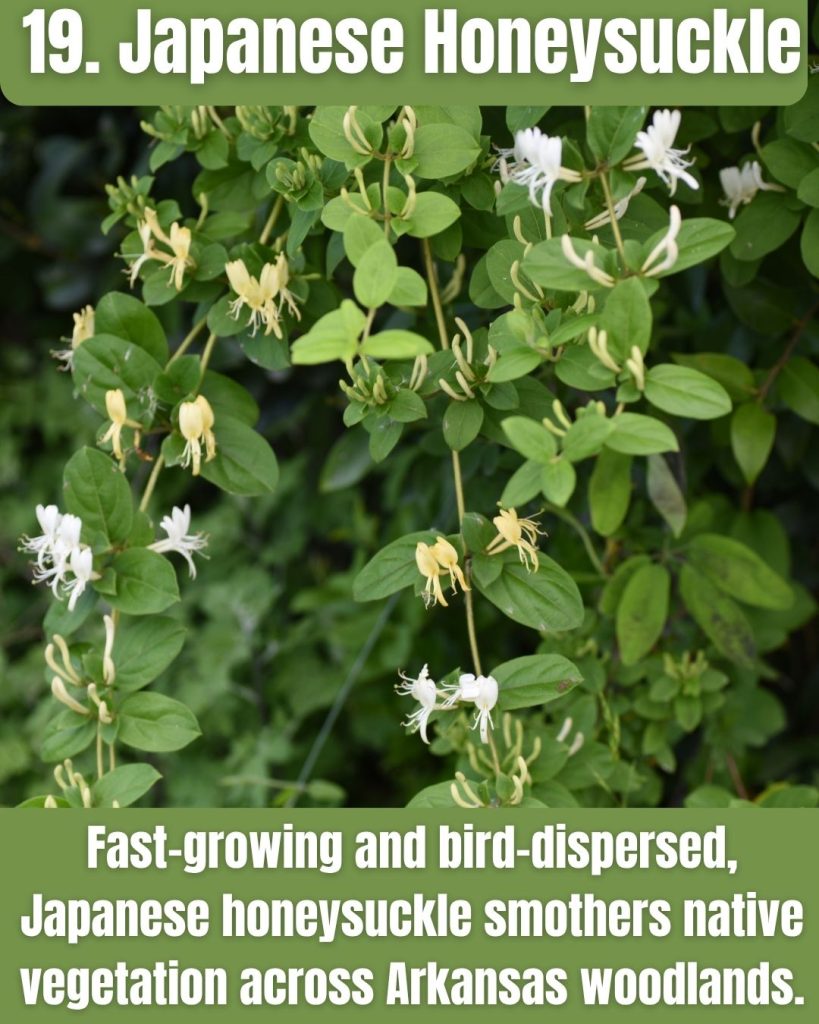

Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)

- Fast-growing vine: Smothers trees and shrubs with dense growth.

- Widespread invader: Common in Arkansas forests, roadsides, and disturbed areas.

- Bird-dispersed: Berries spread widely, helping it invade new sites.

Japanese honeysuckle aggressively invades Arkansas woodlands and edges.

Its thick vines and dense foliage shade out native plants, disrupting forest regeneration.

Invasive Aquatic Species (Fish & Water Plants)

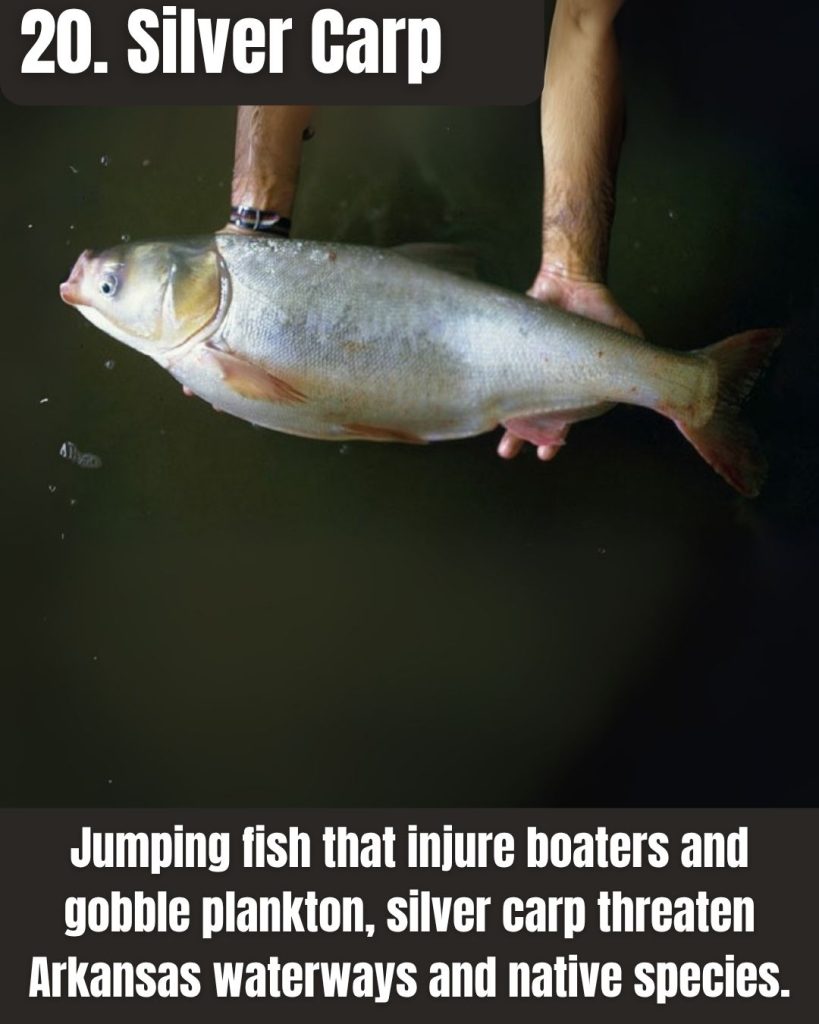

Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix)

- Jump scare: Known for leaping up to 10 feet out of the water when startled, injuring boaters and disrupting recreation.

- Plankton pirates: Filter feeders that consume massive amounts of plankton, robbing native fish and mussels of food.

- River invaders: They now dominate sections of Arkansas’s rivers, outcompeting native fish for space and resources.

Filter-feeding Asian carp dominate plankton in Arkansas’s major rivers, starving paddlefish and young sportfish.

Alarmingly, startled adults can rocket ten feet into the air, injuring boaters and breaking gear—a biological and recreational nightmare.

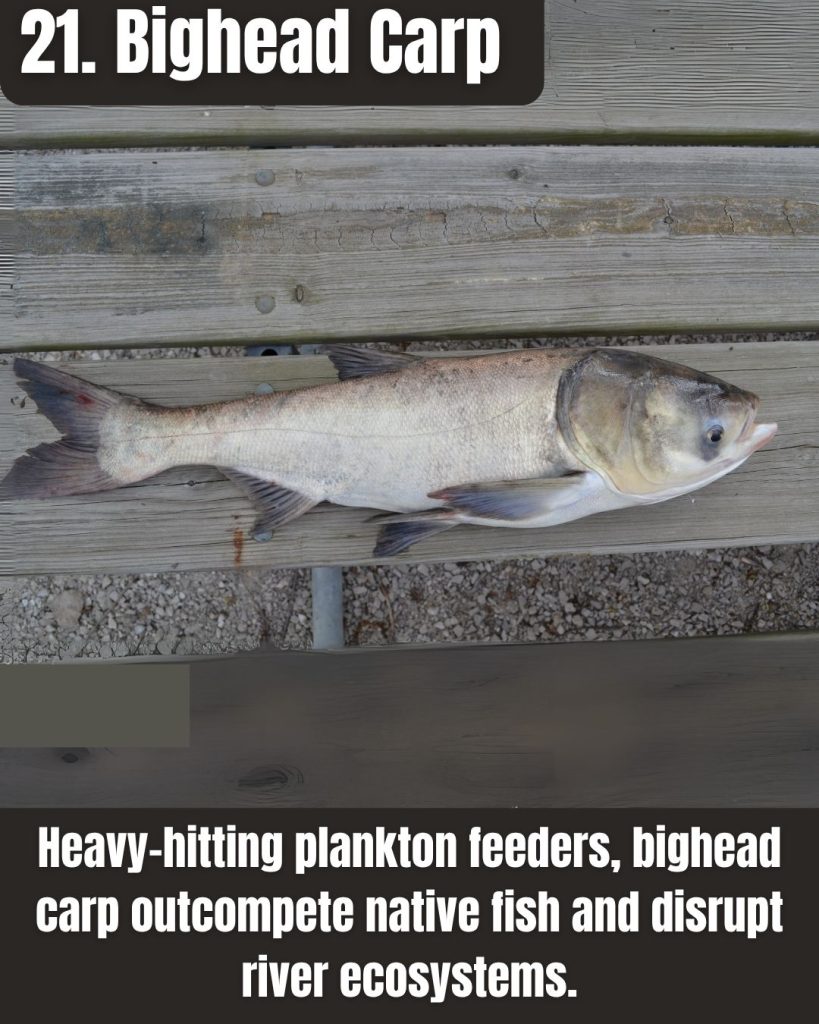

Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis)

- Filter-feeding giants: Can grow over 100 pounds and consume enormous amounts of plankton, starving out native fish and mussels.

- River hogs: Compete directly with paddlefish, buffalo, and young sportfish in Arkansas’s waterways.

- Hard to control: Spawn in large rivers and adapt quickly, making them tough to manage once established.

Weighing up to 80 pounds, bigheads gulp zooplankton by the bucketful, undercutting native fish recruitment.

Though less acrobatic than silver carp, they share the same runaway reproduction and food-web disruption.

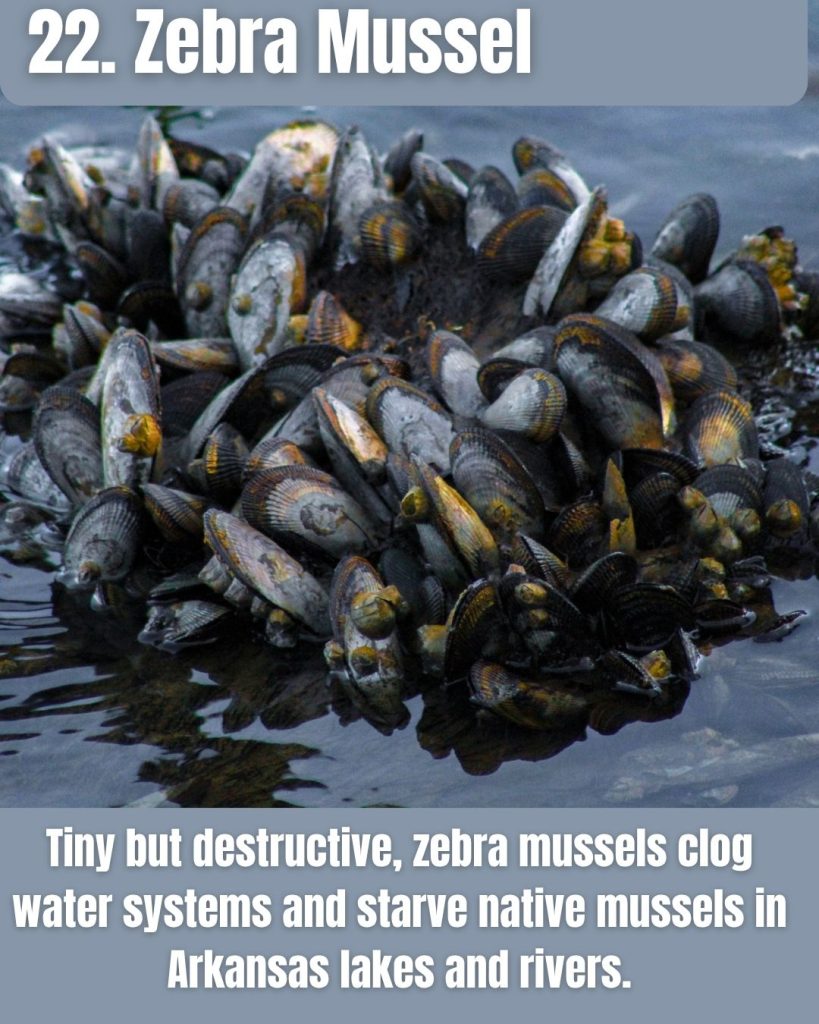

Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorph)

- Tiny takeover: Attach in dense clusters to boats, docks, and water systems, causing millions in damage annually.

- Reproductive machines: Just one female can release up to a million eggs per year, fueling explosive population growth.

- Food chain crashers: Filter out vital plankton, leaving native mussels and young fish without food.

Attached by the millions to pipes, zebra mussels clog water-intake systems and smother native mussels in Arkansas lakes and rivers.

Their voracious filtering strips plankton and can trigger toxic algal blooms.

“Clean, Drain, Dry” remains the state’s mantra for boaters.

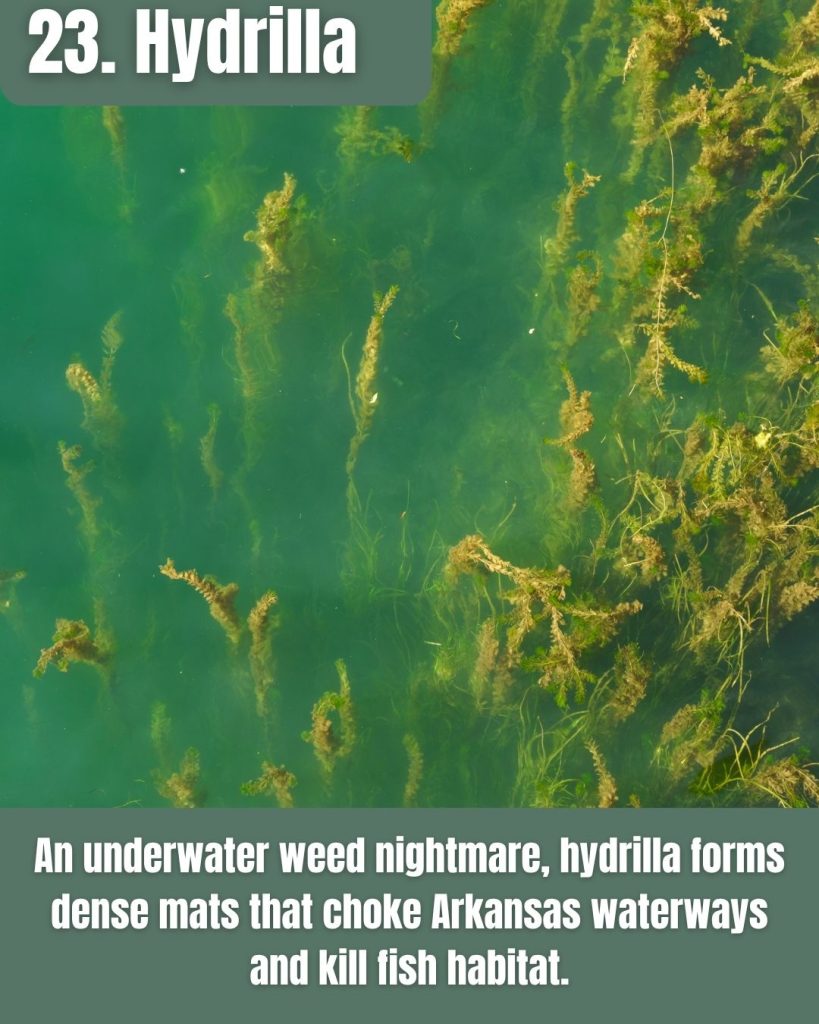

Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata)

- Aquatic weed: Forms thick mats that choke waterways, hindering boating and fishing.

- Rapid spread: Spreads by fragments, making control difficult.

- Oxygen depletion: Dense growth reduces oxygen levels, stressing fish populations.

Hydrilla is one of the most aggressive aquatic plants in Arkansas’s lakes and rivers.

It crowds out native vegetation, impairs water flow, and harms recreational use.

Giant Salvinia (Salvinia molesta)

- Floating fern: Forms dense mats that block sunlight and reduce oxygen in the water.

- Rapid growth: Can double in size in a week, quickly covering entire water bodies.

- Difficult to control: Chemical and biological controls are ongoing but challenging.

Giant salvinia has invaded some Arkansas ponds and slow-moving waters, posing a threat to native aquatic plants and fish habitat.

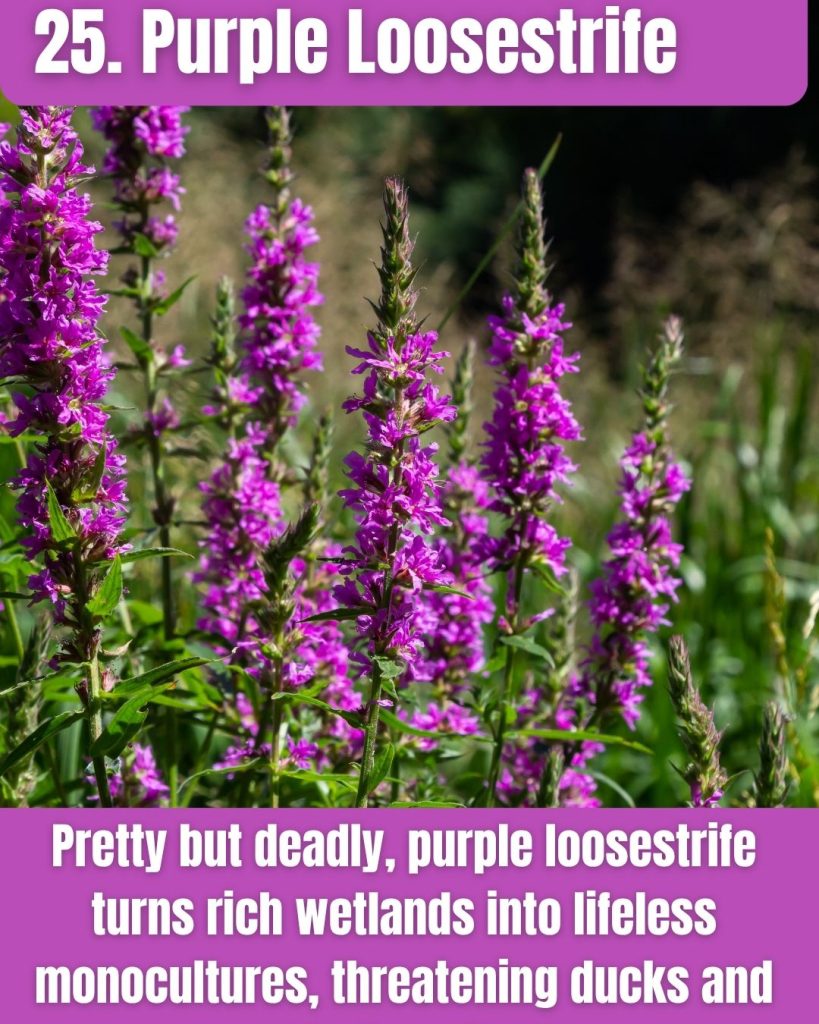

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

- Pretty but perilous: Its tall spikes of purple flowers hide a plant that chokes out native wetland species.

- Seed powerhouse: A single plant can produce over 2 million seeds per year, spreading rapidly along rivers and ditches.

- Habitat killer: Forms dense stands that reduce biodiversity and waterfowl habitat, replacing vital wetland plants.

Beautiful but destructive, purple loosestrife turns biodiverse marshes into monocultures, crowding out cattails and reducing food for ducks.

Each stalk drops millions of seeds, yet beetle biocontrol agents offer hope of keeping this wetland invader in check.